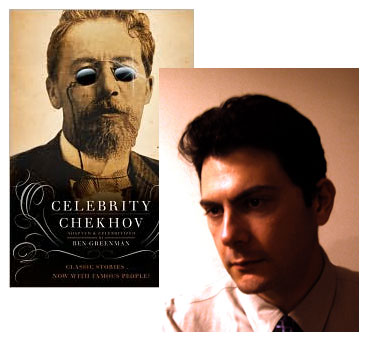

Ben Greenman Revisits Chekhov’s Barber

I’m a big fan of Ben Greenman, and I’ve been trying to get him to do a guest essay for the “Selling Shorts” series for a while. The arrival of his latest short story collection, Celebrity Chekhov, gives us the perfect opportunity. It’s a book with a fantastic, near-Barthelmian “gimmick”: Ben takes twenty-some stories by Anton Chekhov, removes the original characters, and replaces them with contemporary celebrities. (In the story he’s about to discuss, for example, the customer has become Billy Ray Cyrus.) The stories take on new meaning when readers invest them with their acquired attitudes towards the famous personages who’ve been added into the mix—but their original impact is not lost, as Ben explains while telling us about one of his favorites.

Chekhov is one of a handful of short-story writers who I come back to time and time again: the others include Mary Robison, Stanley Elkin, Jorge Luis Borges, Ernest Hemingway, and Joy Williams. It’s not a long list, this set of regular destinations. There are dozens upon dozens of short-story writers I love, obviously,and nearly as many novelists, and I don’t mean any direspect to anyone else. What I mean, I think, is a certain specific kind of respect to these writers. There’s something in their work that I love stealing. For some of them, it’s the way they kick off their first paragraph. For some, it’s the way they draw characters. For some, it’s the way they manage dialogue. For some, it’s the rhythm, or the boldness of their language, or the clarity of their ideas.

Chekhov is one of a handful of short-story writers who I come back to time and time again. This time, I came back to him holding a stick of dynamite, like in a Warner Bros. cartoon. Celebrity Chekhov comes after a series of books that people/critics have read as serious works of straight-faced literature, and because this one isn’t like the others, people are eager to classify it as humor. It isn’t, except in the sense that the original stories are. Sometimes, of course, Chekhov’s original stories were sad, and in those cases I tried to preserve the melancholy, or moral agony. Just as often, though, the originals are comic, perfectly assembled little clockworks of human folly.

Take “At the Barber’s,” an early Chekhov story and one of my favorites. It’s just a touch over 1,200 words, and relates two brief conversations that, between them, take maybe ten minutes. There is only one setting, the barbershop of the title, and only two characters: a young barber and an older customer, both men. But from that potentially claustrophobic formula Chekhov manages to produce a universal tale of hope, greed, and pride. It’s important to add that it’s also an entertainment: the ethical points are made, and made clearly, but the piece never sacrifices its sense of briskness or absurdity.

3 November 2010 | selling shorts |

Read This: The Poetry Home Repair Manual

“A poem is the invited guest of its reader. As readers we open the door of the book or magazine, look into the face of the poem, and decide whether or not to invite it into our lives. No poem has ever entered a reader’s life without an invitation; no poem has the power to force the door open. No one is going to read your poem just because it’s there.”

It may seem unusual to start a set of National Novel Writing Month reading recommendations with a book of “practical advice for beginning poets,” but Ted Kooser’s The Poetry Home Repair Manual has a great deal of useful advice for fiction writers as well. I’m thinking chiefly of Kooser’s principle of poetry as communication, that “[its] purpose is to reach other people and touch their hearts.” For Kooser, that leads you to think of the chosen reader—the imaginary audience you believe will be most receptive to your poems. Who are those readers? What are they looking for? And how can you best deliver your message to them? That’s something that fiction writers would do well to consider as well… and that doesn’t mean, he emphasizes, that you need to pander or reduce your writing to the lowest common denominator. If your imagined reader isn’t afraid of a little difficulty, a little ambiguity, work with that!

(And, on a technical level, too, Kooser’s advice to throw out all the “spare parts” and focus on what matters, to discover inner feelings by writing about what’s observable, or to rein in the reader’s imagination with a well-chosen adjective are as applicable to prose as they are to verse.)

The quote I’ve chosen to share may seem a bit harsh, but it’s also something that’s very important for anybody who’s taking part in NaNoWriMo to remember. I’m not saying you can’t write just for yourself this month; in fact, one valuable function of NaNoWriMo may very well be the opportunity to prove to yourself that you can write a novel, even if that particular novel isn’t one that you’d ever publish. If you are hoping to share the results of the next thirty days (and, most likely, much subsequent revision) with other readers, though, keep in mind that the novel needs to make sense to someone else besides you. I’ve sometimes given the advice (hardly original to me) that you should imagine the type of fiction you’d most to read but aren’t finding from other authors, then write that. To that, with this in mind, I would add that such fiction shouldn’t be a private gift, for your eyes only. As Kooser observes, “The more narrowly you define the reader, the more difficult it will be to put your poem someplace where that reader might come upon it…. the more difficult it becomes for your poem to contact him or her.”

1 November 2010 | books for creatives, read this |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.