Tiphanie Yanique: The Tone of “Near-Extinct Birds”

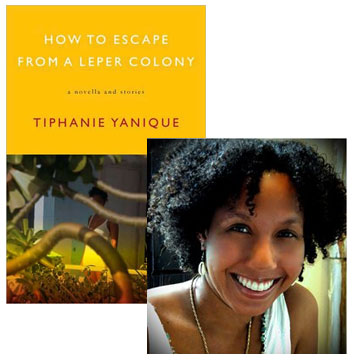

Tonight, Tiphanie Yanique will be honored by the National Book Foundation as one of the “5 Under 35,” their annual tribute to a select group of promising young writers. She’s being recognized for the strength of How to Escape a Leper Colony, a fantastic collection of short stories that have already earned her an award from the Rona Jaffe Foundation as well. The breadth of Yanique’s storytelling is quite impressive—be sure to read the novella “The International House of Coffins,” which takes one encounter between three people and spins it in three very different directions—and, as she explains in this guest essay, that’s a quality that she consciously strived for. Don’t just take my word for it, though: You can read the title story, which won the Boston Review fiction prize, and if you like that, pick up the book and try the rest.

I love Ben Fountain’s Brief Encounters with Che Guevera for many reasons, but in particular because of something his collection does that many collections just don’t do: range. Range is one of the things I think a story collection can do more easily than a novel, and yet it’s something that collections often refrain from attempting. When a collection does attempt range often reviewers and readers just don’t know what to do with it.

By range, I mean that each story in a collection attempts something different. Fountain’s title story is mostly realist, about an Ameircan kid working in furniture delivery. Another story, “Fantasy for Eleven Fingers,” about a piano savant with an extra finger, is filled with fancy. Some stories are from inside of a culture as with “Bouki and the Cocaine,” told from the perspective of Haitian fisherman, and others are from the outside looking in, as with “Rêve Haitien,” told from the perspective of an American expat in Haiti. The stories are set in the Caribbean, South America, North America, Asia, Europe and Africa. While most of the stories are from the male perspective, there are standouts from women characters. Most of the stories are third person and from a white American perspective, but not all. This range is something I attempt in How to Escape from a Leper Colony in part because Fountain’s collection allowed me to know it could be successful. I didn’t realize how perilous this might be.

Reviewers each seem absolutely sure of which story is “the best” story in a collection. The first few reviews of my book mentioned the title story as the strongest. I believe in learning from criticism, so at first I bought this. But as more reviews came out there turned out to be no consistency with what was “the best.” One critic on NPR praised my shortest stories, but just a week later a print review declared the longer stories superior. At one reading there was consensus that “Street Man” was the best, but then at another it was “The International Shop of Coffins.” A close friend said that “The Saving Work” was the strongest story, but I confessed that I most enjoyed reading “Kill the Rabbits.” At a book club one woman declared that “Where Tourists Don’t Go” was the best. It’s wonderful to think that each story might reach a very different reader. The peril is that the other stories might quickly be judged inferior.

On the other hand, a great pleasure comes in teaching a collection like Ben Fountain’s. Each story in Brief Encounters with Che Guevera offers something unique about craft. In “Fantasy for Eleven Fingers” my students and I discuss timing and the use of history to give shape to a story. In the title story we talk about structure. In “The Good Ones Are Already Taken,” we go over the use of fairytale or religion in crafting character In “Bouki and the Cocaine,” we discuss the impact of history and culture on plot possibilities. When you’ve read one Ben Fountain story, you just haven’t read them all.

The best story in the collection is “Near-Extinct Birds of the Central Cordillera.” But of course I’m lying. In a collection with range, the most anyone does by saying “best” is reveal her temporary bias. “Near-Extinct” is simply the story that was my favorite the first time I read the collection.

The tone of this story is immediately urgent, naive and hopeful. This also describes the main character, John Blair, a passionate Ph.D. student studying birds in the rebel territory of Columbia. The story is in third person, but Fountain doesn’t let that get in the way of giving us a specifically crafted tone. In an effort to explain the importance of finding these birds the story says: “It could be done; it would be done; it had to be done.” We know already that poor John was equally as sure that the rebels would never capture him, but by the time when we meet him he’s just been kidnapped.

When we see John marching in the jungle, a captive, we already believe that earnestness would allow him notice and note the species of birds that he sees along the way, despite being scared for his life. During his first interview with the commandante, he would attempt to negotiate his own release by explaining in tears that “if I’m not back at Duke in two weeks… they’re going to give my teaching assistant slot to somebody else.” We believe this because the tone has already set it up. Out of tone came character.

Once we know John the plot is in high gear. John is a naïve white American kidnapped by Columbian rebels! Will he be rescued? Will he die in the rebel camp? Will he become a rebel? Then out of this plot there comes conflict. John is a captive, but eventually he’s given the freedom to study the birds. We see him wilting away under the extremes of captivity, but we also see him making scientific discoveries even he didn’t think was possible. Now we begin to wonder, which is more important to John; his freedom or his research? The story is a perfect example of how elements of craft arise out of each other.

Most collections just don’t have the problem or pleasure of range. Often an entire collection is working inside of one voice, quite often in the same gender and race. These stories might feel as though each character, though differently named, is the same character just at different points of his or her life. These collections can be incredibly satisfying, echoing some of the pleasures of the novel. But I would also argue that one of things that a story collection can do is present virtuosity. The risk is that on a first read virtuosity might seem like inconsistency. So it’s up to us readers to not let a great story, or entire collection for that matter, get forgotten based on our initial biases. Actually, “Near-Extinct” isn’t my favorite story in the collection anymore. Now it’s the title story. But then again, I never did quite get “Fantasy for Eleven Fingers.” Maybe I should read that one again…

15 November 2010 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.