We Are All Book Banners Now

Somebody found a book in Amazon’s Kindle Store Wednesday. I’m not going to tell you what the book is, but I will tell you that it is sympathetic towards what may well be the only truly universal taboo in Western sexuality, so you can pretty much guess at how disgusting it is, and if I owned a bookstore, I would have absolutely no qualms about not carrying it or ordering it in. It’s not a First Amendment issue, because a corporation is not a government. When I worked at Amazon in the late 1990s, however, there was an absolute commitment to providing customers with access to any (legally published) book they wanted, and a firm line drawn against recognizing demands that Amazon stop making any given book available.

“We don’t think customers want us picking what we think is appropriate for them to read” was the official response in 2007, when a similar controversy erupted over the sale of dogfighting-themed magazines and videos—which tied in with the attitude I described as prevailing when I was an employee: “If you give in on the really blatant ‘boylove’ stuff, the reasoning ran, eventually somebody comes after you for the Jock Sturges and Sally Mann books, so you had to keep the goalposts all the way at the end of the field to keep everything in play.” If you give in to one demand to suppress a book from inventory, you invite future demands, and once you’ve set the precedent, it makes it that much harder for you to tell the next person “No.”

Because, make no mistake about it: While this isn’t a First Amendment issue, everybody who began demanding Amazon stop carrying that book was, at the level of intentionality, the equivalent of a book banner. If you don’t think so, ask yourself this question: How would you react if your public library carried that book? “I am doing exactly what I MOST hate about book banners,” Ana from The Book Smugglers admitted. And Harry Markov conceded the dilemma: “if I demand to censor it, I betray the principle I stand behind. If I don’t demand something be done about this book, then I betray the values I have been brought up with. In this situation I feel so helpless.”

So, yes, it’s instructive to watch people who would ordinarily deplore book banning confront a book that genuinely appalls them, and for those who value the suspension of moral judgment in the interest of customer satisfaction, it was encouraging to see Amazon initially stand by its position of carrying everything for everybody, even as offended consumers threatened boycotts—which are themselves a perfectly fine consumer response. (If you think a company is doing something you can’t support, by all means stop supporting them.) The problem was that, as the day progressed, thousands of consumers started making those demands, and then the mainstream press started to fan the flames.

Fortunately, for Amazon, a loophole existed: Because the Kindle edition (the only available edition of the book, as far as anybody can determine) was self-published through technology that Amazon provides, it was able to fall back on “Digital Content Guidelines” which state, in part: “What we deem offensive is probably about what you would expect. Amazon Digital Services, Inc. reserves the right to determine the appropriateness of Titles sold on our site.” At least I assume that’s the loophole Amazon used; the company never actually said anything about their decision to yank the title from its inventory late Wednesday night, and as of Thursday night still hadn’t said anything. It just happened.

The online media reaction to Amazon’s decision yesterday was mixed. If you ask Irin Carmon of Jezebel, it’s just business; The Stranger book editor Paul Constant, on the other hand, believes Amazon has thrown away one of its principles. Over at Techcrunch, Devin Coldewey made a very insightful point: “Wherever Amazon chooses to stand after this incident, someone will define themselves by its shadow.” So who is going to be the online bookstore that holds firm to a “if you want it, we can sell it to you” commitment? (Or, in my more cynical formulation, “we don’t judge you, we just want your money.”)

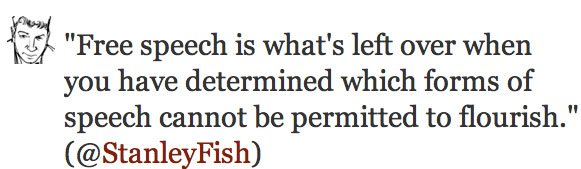

Meanwhile, “what the ban most certainly is not is an anti-pedophile victory of any meaningful kind,” adds Paul Carr (another Techcrunch correspondent). All this brouhaha established is that most of us aren’t as different as we’d like to think we are from the people we’ve made into villains for trying to suppress books that support, or even just describe, things they don’t like. It’s only a question of where each of us chooses to draw the line, and whether or not the rest of society reinforces our values. That’s not necessarily a bad thing, either. I believe Harry Callahan said it best:

12 November 2010 | theory |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.