Paul Muldoon, “A Mayfly”

A mayfly taking off from a spike of mullein

would blunder into Deichtine’s mouth to become Cuchulainn,

Cuchulainn who had it within him to steer clear

of a battlefield on the shaft of his own spear,

his own spear from which he managed to augur

the fate of that part-time cataloguer,

that cataloguer who might yet transcend the crush

as its own tumult transcends the thrush,

the thrush that’s known to have tipped off avalanches

from the larch’s lowest branches,

the lowest branches of the larch

that model themselves after a triumphal arch,

a triumphal arch made of the femora

of a woman who’s even now filed under Ephemera.

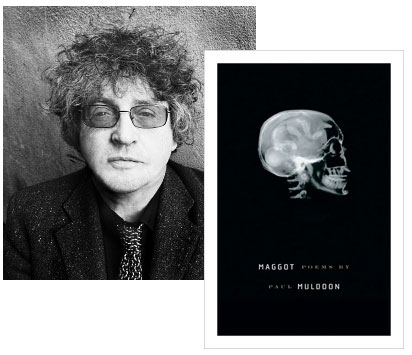

Maggot is the eleventh volume of poems from Paul Muldoon, who’s currently serving as the poetry editor at The New Yorker. In that capacity, he’s taking part in a charity auction for Housing Initiatives of Princeton, offering himself up as three separate prizes: you could get a private reading of some of his poems; you could get a one-on-one consult about your own verse; you might even try for the guided tour of the New Yorker offices. The bidding runs through October 28, 2010, with a party at Princeton’s Present Day Club two nights later.

“Poetry is as vital as ever,” Muldoon recently told The Economist. “The teaching of poetry reading, however, is sluggish and, often, slovenly. It needs to be expanded in the school curriculum and be more a feature of society at large. The newspapers should all be carrying a daily poem. It should be as natural as reading a novel.” In the meantime, we do what we can.

11 October 2010 | poetry |

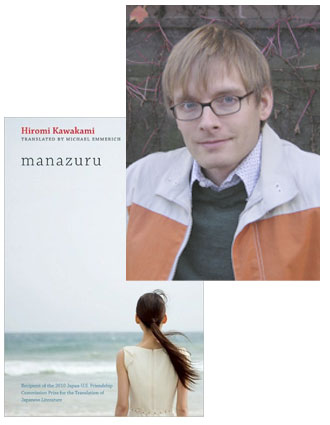

Michael Emmerich & The Manazuru Tuning Fork

The biggest reason for people in the U.S. to read more translations is that there’s a hell of a lot of amazing stuff being written… all around the world,” Michael Emmerich told The Quarterly Conversation a while back. “Most of us have, at least one point in our lives, come across writers or books that really changed the way we think, or feel, or what we like or something else about us. There are a lot of terrific writers working in English, of course, but there are even more writing in other languages. Who knows, maybe a book has already been written in some other place, in some other language, that would really change my life and the way I look at things, if only I knew about it?” It could even be that Manazuru, the latest of Emmerich’s translations of contemporary Japanese literature, could be that book. Hiromi Kawakami’s novel is a (haunting? unnverving?) story about a woman who’s still working through the disappearance of her husband twelve years earlier, drifting through her present relationships and occasionally becoming unmoored from the world around her. It’s not, as Emmerich explains in this essay, an easy novel to translate, but he’s found a very powerful solution.

From a translator’s perspective, not all books are equal. Some are a joy to translate, some are not. Some books seem to struggle with all their might against being rewritten in English, while others seem almost to have been waiting for a translator to appear, to complete a metamorphosis that has already begun, in some mysterious way, in the language of the original. It is not always easy to tell beforehand which type, or combination of types, a certain book will be: extremely difficult to translate and not at all fun, or difficult and rewarding, or easy and dreadfully dull.

Translating Hiromi Kawakami’s Manazuru was a startlingly easy joy. I remember that when I first read this novel, before there was any discussion of my translating it, I found myself thinking that it would be all but impossible to create an English echo of its terse, resonant, and subtly strange prose. Kawakami has a penchant for words that don’t sit easily in modern Japanese—classical vocabulary that feels slightly odd, that refuses to blend in, and yet somehow also feels precisely right. The Japanese language has a long history, and every so often Kawakami will use a thousand-year-old word that is recognizable, if it is recognizable, only because of the slight family resemblance it bears to a modern descendant. In Manazuru, Kawakami also uses unusual punctuation: she puts commas and periods in places where one would not normally expect to find them, and leaves out expected quotation marks. She also exploits to the full the inherent tendency of Japanese prose to drift effortlessly back and forth between what would usually be thought of, in English terms, as past and present tense.

Manazuru‘s prose was odd and wonderful. It urged readers to read slowly, and rewarded them if they did. A good translation, I thought, would have to create a voice in English that breathes the way the prose of the Japanese does. It would have to be quirky and unsettling, but at the same time convincing. It would be hard to pull off, especially given the culture of translation in the English-speaking world, in which many readers and reviewers seem to expect translations to be written in some fantasy “standard English.” In order to translate Manazuru effectively, one would have to create a voice in English so compelling, so alive, that even readers accustomed to faulting translators for each and every apparent “irregularity” in their English rewritings of foreign texts would be persuaded to accept the odd rhythms, startling word choices, peculiar punctuation, and sudden shifts in tense. They would have to be convinced to see the strangeness, not as a lack of smoothness, but as part of what makes this novel, Manazuru, so rich.

9 October 2010 | in translation |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.