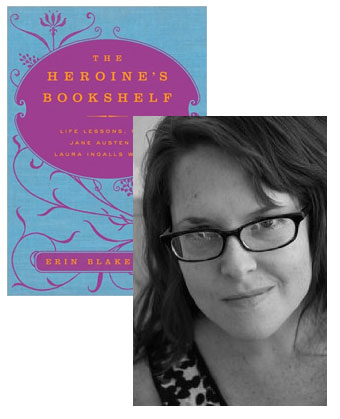

Erin Blakemore: Standing Down Literary Intimidation

The “Intimidation” that Erin Blakemore writes about in the essay you’re about to read is of a kind with the Resistance Steven Pressfield discusses in The War of Art, one of my all-time favorite books about creativity, and we’re fortunate that Blakemore prevailed and completed The Heroine’s Bookshelf, a delightful guide to what the heroines of some of the great novels by women writers, and those writers themselves—from Pride and Prejudice to The Color Purple, or from Laura Ingalls Wilder to Colette—can teach us about life.

By the way, New Yorkers: If you’re free Tuesday evening (October 26), you might join Blakemore at Bookbook (266 Bleecker Street) at 6:15 p.m., where she’ll kick off a women’s literary walking tour of Greenwich Village—you’ll see the house where Louisa May Alcott wrote Little Women as well as the homes of authors like Edith Wharton, Edna St. Vincent Millay, and Alice Walker—followed by a discussion back at the bookshop. If you do decide to go, and you’re on Facebook, please RSVP; it’s always helpful to have an idea of how many people might show up!

The longish pause that separated my book deal from my book writing really shouldn’t have happened. I was on a tight deadline, inundated with commitments to my day job, and riding high on the wave of a debut book contract. What was my problem, again?

I blamed. Myself, of course. Couldn’t I have picked a less intimidating subject than the great heroines and authors of literatures for my first published book? Sadly, I was the kid at school whose arm went numb with handraising and who always chose the 3,000-page tome when the 30-page children’s book would do. Add overachievement to hubris and BANG, there I was, popcorn seeds all over my pajama top, wringing my hands over the blinking cursor at 4 a.m.

Weak.

I procrastinated. It comes naturally to the intimidated writer; a sudden fascination with research that’s “all-encompassing” and extremely convenient. Better to write down what another had written than venture a word of my own. This went far beyond mere newbie foible. After all, I knew from deadlines; I’d made my living from that blinking cursor for several years. I knew what I was up to.

I got smacked in the face. Since the story of how the deadline eventually cracked itself against my head is so cliché it hardly bears repeating, I’d rather focus on what happened inside that panic to produce. I, the one who talks her way through every problem, who works things out with words, was forced to listen up.

And so, I listened. I wiped off my face and tuned in to my own subject matter. Turns out the literati I had feared—Harper Lee, Jane Austen, Betty Smith—had all struggled to get their own work done. My literary heroines were playing a game of dysfunction chicken, struggling to outdo one another with tales of writing through personal tragedy, subsisting on money their children found on the ground, surviving freezing winters and feeding their addiction to Victorian-era painkillers while scribbling frantically for money.

Ohhhhh. Not that intimidating. It became easier to know that my work was as freckled as my own face, that I still had much to learn.

I write this because the work got done and I got closer to my subjects in the process, and in the hopes of helping others dispel the intimidation that comes when you’re standing at the front door, unsure of how to operate. I now believe that the mechanism of intimidation, the seduction of “I can’t,” is a fabulous mental invention, something created to shield us from what’s big and bright, what could hurt our eyes and ears. In my case, literary intimidation was an excuse not to enjoy my own work, not to allow myself the uncertain pleasure of a process which has torn me down, built me up, beamed me out to people I’ll never meet. Coaxed out of bed by long-dead literary mentors, I’m doing what’s in front of me, ignoring Intimidation’s text messages, and getting back to work.

25 October 2010 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.