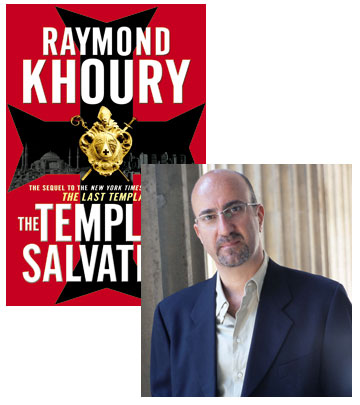

Raymond Khoury’s Long Pilgrimage to Success

Today is the official publication date for Raymond Khoury‘s The Templar Salvation, and an excellent time to look back at the roundabout way its predecessor, The Last Templar, found its way to publication and from there to the bestseller lists. It’s a story that reminds us—the only person who can absolutely keep a book from getting published is the author who quits believing in it.

I remember the phone call: London, 2006. Around 11 p.m., walking out of a football game on a cold January night. It was my editor in New York. Despite the 3,000 miles separating us, the ambient post-match chaos, and his Zen-like composed tone, I could tell something good was up.

It was way more than good.

My first novel, The Last Templar, the one he had championed, had hit the New York Times bestseller list at #10 in its first week.

The calls kept coming for 3 months, every Wednesday night, as, astonishingly, the book climbed up the list after that first call: to #6, #5, then #4, with only three stellar names ahead of me: James Patterson, Stephen King and Dan Brown. I say astonishingly, because I never, ever expected any of that. I’d been hoping for, maybe, a week on the extended list. But I did take immense pleasure in it all, given that its saga had begun over ten years earlier.

Cycle back to 1994. I’m a budding screenwriter. No agent. Nothing sold yet. Photocopying my screenplays (two at that point) and DHL’ing them (the pre-email dark ages) to movie industry contacts like, for instance, someone who knew someone who’d once bumped into Stephen Spielberg’s dog-walker in a park. That level of connection. And, surprisingly, not getting results.

Those first two screenplays had been small, personal. And here I was, hanging out with some friends in France, frustrated, telling them I felt like writing something big, epic, a summer movie that the studios would fight over. And a buddy of mine said, What about the Templars?

Boom.

I knew next to nothing about them. But I spent that weekend reading up—the warrior monks’ rise and fall is a massively popular story in France, has been for centuries—and by the end of it I knew I had my big, summer epic.

The screenplay took around a year and a half to write. Then the fun—and by fun, I mean pain—began.

I started working my connections—the dog-walker’s rumored acquaintance and so on—when I got a call from an agent. A big hitter. A real one. He’s read the screenplay. Loved it. But: he wasn’t a movie agent. He was a book agent. And his suggestion was this: let’s turn the screenplay into a novel. Get it published. Sell the film rights to the novel—which, hey presto, would be my screenplay.

The first publisher to get offered the story pounced on it. Huge six-figure advance, film rights to be optioned too. They flew me to New York. Sat me down, told me all their grand plans for the book.

Then the caveat: “Lose the religion.”

The Templars’ lost treasure, some big secret? Nah. Boring. Gold, jewels, that kind of thing. That’s exciting. “No one’s interested in some lost gospel.” This, coming from the gods of the publishing world.

I spent three nights alone in a Manhattan hotel room, agonizing over what to do. Surely, these people knew what they were doing. They publish #1 bestsellers, for Chrissakes. And it’s a ton of money.

I couldn’t do it.

I said no and walked away, feeling like the biggest dope on the planet. Worse, a couple of weeks later that summer, the film rights to this unwritten ‘novel’—sans the ‘lose the religion’, so maybe, ‘avec the religion’—were offered to the studios. Asking price ran seven figures. Just so you understand how it works: Production companies (one per studio, handpicked) get offered it first. If they like it, they kick it upstairs for the studio execs to buy it for them. It’s sent out by the legend of film right sales on a Wednesday. Thursday night’s call: lots of yeses. I spend the weekend thinking this might actually work out, drawing up my fantasy cast list and wondering how I was going to avoid being a slobbering fool when I had dinner with Sharon Stone. Monday’s call whipped me back to reality. All nos. Reason: too controversial for the mainstream, too expensive to make for the more adventurous.

It did, however, kick my screenwriting career into gear. I was getting work off the back of it and selling other specs to the studios. Then along came the new millennium and I changed agencies, moving to William Morris. A book agent there heard about the saga. Called me up. Told me, “You must write this book. With everything you put in the screenplay. You. Must. Do. This.”

She called every couple of months. “Have you started it yet?”

Later, mostly to get her off my back, I started it. Zero expectation. Just hoping to exorcise a demon from my past. Then two things happened.

9/11. And The Da Vinci Code.

The former turned religious conflict into a hot issue. The latter came out when I was halfway through writing my book. I read it. Loved it. And called my agent and told her I was dropping Templar. Dan Brown had done a great job exploring some of the less-well-known aspects of early Christianity—the theme at the core of my book.

To her great credit, she insisted I keep going, telling me my book was very different, using some kind of Jedi mind trick that kept me going, slowly—in time for my next dose of pain.

Rejections. From all twelve publishers in London who were shown the finished book in late 2004.

They professed to love the book, but were passing for one of two reasons: either they already had books in the pipeline that had been set-up following the success of The Da Vinci Code or they thought the market would already be saturated by the time Templar would hit the shelves.

Then, a chance encounter. In a restaurant. A TV director, old acquaintance, had tried to direct a screenplay of mine a few years earlier. I tell him what I’ve been up to. He says, “Let me publish it.”

He’d published one book. A year earlier. A novel for kids. (And, to give him his due, it had done reasonably well, with several foreign translations.)

At this point, I just wanted it out of my life. So I said—this is in March 2005, in an industry where if you’re reading a bestseller by one of your favorite authors, chances are his or her publisher already has the manuscript of their next book well in hand—I said, okay, if it can be in the stores that summer. Three months later. I couldn’t bear the idea of living with the damn thing a whole other year.

His answer? “Let’s do it.”

A graphic designer buddy of mine and I came up with a cover in three days (not the iconic one with the red cross; that came later), and my presumed publisher had some bound proofs printed up.

Then the world shifted.

My agents went out to foreign publishers with the proofs of the book that was soon to be published in the UK (by a TV director, but they didn’t mention that). And got bids. Lots of them. The Last Templar went to bidding wars in all the major territories…

Yes, many people assumed it had been written to surf the Da Vinci Code wave.

Yes, it annoyed me to be asked if I had.

But you know what? As I contemplate the forthcoming release of its sequel, The Templar Salvation, after writing two other stand-alone bestsellers in between, I couldn’t be happier. The truth is, things worked out beautifully. I don’t think I was ready to write that book back in 1996. And maybe readers weren’t ready for it either back then. Dan Brown’s success created a hunger for the topic that many other writers, me included, benefited from. And it allowed me, four years later, to have a blast with the characters that had haunted me for all those years and enjoy their company while torturing them, for a change, in the sequel.

I hope you all enjoy it as much as I did.

19 October 2010 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.