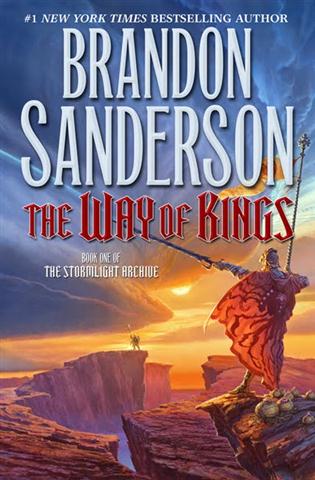

Read This: The Way of Kings

I’ve got another review in Shelf Awareness this week—today they’re running my take on Brandon Sanderson’s The Way of Kings, the first volume in a new series called “The Stormlight Archive.” I jumped at this assignment because I’ve been meaning to read Sanderson for a while, but I’d never been able to carve out time from my other obligations and dedicate it to reading one of his massive epic fantasies. So now that it’s one of my jobs to read fantasy… well, you can see where I’m going with that idea.

I’ve got another review in Shelf Awareness this week—today they’re running my take on Brandon Sanderson’s The Way of Kings, the first volume in a new series called “The Stormlight Archive.” I jumped at this assignment because I’ve been meaning to read Sanderson for a while, but I’d never been able to carve out time from my other obligations and dedicate it to reading one of his massive epic fantasies. So now that it’s one of my jobs to read fantasy… well, you can see where I’m going with that idea.

In my review, I talk about one thing that frustrates me about The Way of Kings, which has to do with its very nature as the kickoff to a multi-book story, as “every bit of closure is counterweighted with another narrative opening.” It’s especially frustrating because, once you’ve read through nearly 1,000 pages and begun to see how Sanderson is going to connect his three main narrative tracks (along with one key secondary story), things don’t really end; they just pause with heavy, heavy foreshadowing. And, by then, you are extremely likely to care how all of this fits together, and to want the answers fully elaborated now, dammit. And it’s not just about the former middle-class boy turned soldier turned slave who may or may not have a future in supernaturally-powered redemption, the brother to the slain king who is trying to preserve the kingdom while his nephew dithers in a military quagmire, or the young girl who wants to apprentice herself to the king’s sister with the hidden goal of stealing a magic talisman that might save her family from ruin. In addition to those stories, Sanderson has already laid the groundwork for a high fantasy take on the development of a scientific mindset comparable to the Renaissance or the Enlightenment, and he’s also provided enough momentary glimpses into other corners of his imaginary kingdom to indicate several possible narrative openings. I’m already curious about what will happen next.

2 September 2010 | read this |

On the Refinement of the Modern Book Review

I finished Freedom today, and I’ll have more to say on that later, after I’ve read Fly Away Home—for now, I wanted to touch briefly upon somethng that’s come to mind a lot as I’ve been watching the debate over the attention paid to Jonathan Franzen, and was neatly summarized in NPR’s take on it all:

“Sam Tanenhaus acknowledges that the critical establishment takes certain kinds of books more seriously than others, but he insists there are no criteria used to decide what the Times will or will not review—the goal is to find books that will engage their readers and interest their reviewers. ‘For us as editors, reviewers and critics, what we are really try[ing] to do is … identify that fiction that really will endure,’ Tanenhaus says.”

Let’s ignore, for the moment, the ways in which Tanenhaus’s own (truncated) statement about his (and his colleagues’ and peers’) goals potentially refutes the more expansive attitude ascribed to him by Lynn Neary in the sentence immediately preceding. And, yes, let’s be fully prepared to acknowledge the possibility that the Times, among other publications, has considered that the fiction of authors like Jennifer Weiner and Jodi Picoult engages quite a few readers, and that it is simply uninterested in attracting that sort of person for its own audience. I’m really most interested in the notion that “editors, reviewers and critics” have the luxury of concentrating on “fiction that will really endure,” or at least that they’d like to think will endure. I’m fascinated by that attitude because almost no other desk in the arts section gets to work that way. Can you imagine, for example, if the film reviewers felt like they had a free pass to ignore The Expendables or Eat Pray Love, or the music critics spent all their time writing about Rufus Wainwright and never had anything to say about Justin Bieber. Heck, even the Times restaurant critic occasionally takes the time to visit a restaurant not because it will “endure,” but because it’s popular. The only other department I can think of that might operate the way Tanenhaus advocates is the fine art critic… and is that really the niche in which we want to place contemporary fiction: as a collection of gallery/museum pieces?

1 September 2010 | uncategorized |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.