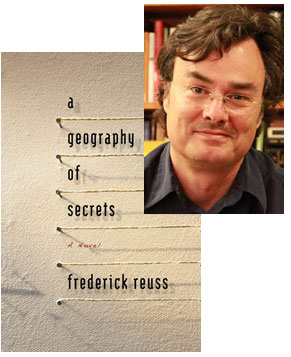

Frederick Reuss: Mapping Out Our Own Territories

A Geography of Secrets traffics in the territory of international thrillers, but its concerns are much more intimate and personal. Some of it is the story of of Noel, who works at the Defense Intelligence Analysis Center plotting coordinates for the U.S. military to drop bombs in Afghanistan, and is undergoing a serious crisis of faith at both work and home—but it’s also the story of the unnamed narrator, who has only the briefest encounter with Noel and is much more concerned with uncovering the truth about his recently deceased father, who may have been more than a career Foreign Service diplomat. The narrator does have cartography in common with Noel, though, and Frederick Reuss leads each chapter of the novel with the longitude and latitude coordinates for the setting. (You can verify this in Google Earth.) In this essay, Reuss explains how technological capabilities open up literary possibilities.

Growing up, my father always made a game of travel. He called it “exploring.” Whenever we arrived in a new place he’d always go off—usually on his own—and then suddenly reappear with a big “surprise” smile on his face. I came to appreciate his methods when I began my own solo travels. In my twenties, I did my first transcontinental road trip on a motorcycle—inspired, like so many others back then, by Robert Pirsig’s Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. Reading a map on a bike isn’t an easy thing to do. I had a compass mounted on the gas tank, vowed to stay off interstates, took only secondary roads and rode around lost much of the time.

You notice things when you’re lost, things that might otherwise go unnoticed—big and little details, features of land and cityscape. There is no better way to discover and become situated in an unfamiliar place than to be lost in it for a time. To draw one’s own map, even a crude one, or trace one’s progress on a printed chart is the ultimate way of connecting to and locating oneself in a landscape.

If my motorcycle trip would have been utterly different with GPS or Google Earth, writing A Geography of Secrets would have been impossible without them. The geo-coordinates that start each chapter form a map of the cartographer/narrator’s quest, a subjective triangulation of the world to bring order and coherence to his life. Geotagging, which has evolved with Google Earth into a kind of hobby and game, is an intriguing new form of self expression—photographic projections, by people, of their presence on the globe. It shows how deeply the urge to locate and be located goes. Satellite photography shows us where we are. (I can see my house from here!)

It also shows the mark we have made on the earth’s surface, our presence. Washington, D.C., was conceived and laid out by the French architect, Pierre L’Enfant, to reflect the highest aspirations and ideals of the Enlightenment—liberty, equality, fraternity. You can see his plan from space: the diamond shape, the circles, parks and grand avenues, all those familiar buildings and monuments, White House, Capitol, National Mall. The seat of government for a democratic state. But the technology also reminds us of what can’t be seen. To look down at Washington, D.C., from Google Earth is to be reminded how much of the city is inaccessible to ordinary citizens.

Today the word most used when talking about the relationship of the state to the people is “transparency.” A cliché tossed around by bureaucrats, politicians and think tank denizens—and an odd choice of words, since to be transparent also means to be invisible. An exposé called “Top Secret America” that appeared this summer in The Washington Post quantified and examined that invisibility beautifully. Although I finished writing the novel long before the Post article appeared, I felt as if I’d entered the aorta of the zeitgeist when I read it. On the Post web site are maps and maps and more maps, brilliantly conceived. They put into high relief just how opaque the land and cityscape surrounding us really is—not just in Washington, D.C., but around the entire country. And, yes, how transparent (i.e., invisible) the state has become.

So we need more than Google Earth to find our way around and behind the facades—just as we need to know more than where we are to know who we are. Map making and following must be imaginative acts. The Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, enshrined in the National Archives, are the foundational documents of the United States of America. But the continental landmass to the west of Europe takes its name from Martin Waldseemüller’s World Map of 1507—which was drawn “according to the account of Ptolemy and the voyages of Amerigo Vespucci and others”—and was dubbed the birth certificate of America when the only surviving copy of it was acquired by the Library of Congress in 2001.

On the map that named America, the continent was only just beginning to take shape. Gerard Mercator’s 1538 map of the world shows the outline of both North and South America and was one of the first attempts to project the sphere of the earth onto a flat sheet of paper. He relied on mathematical calculations, geometry, and the accounts of explorers to draw his maps. His most famous map, called Mercator’s Projection (1569), depicts the globe essentially as we know it today—and, like Waldseemüller, Mercator never traveled beyond Holland and northern Germany (and endured the era of spiritual transparency called the Inquisition).

Google Earth allows us to travel the globe virtually. But now that we can see our houses from space, when every square foot of the earth’s surface is instantly observable and one can have an exact location, rate and direction of travel at any given moment—where have the boundaries of familiar and unfamiliar been moved to? What does it mean to be lost?

15 September 2010 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.