Angie Chau Thinks About “Every Little Hurricane”

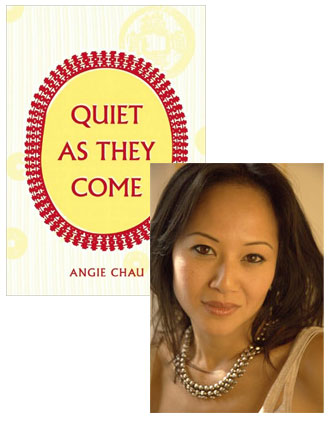

Quiet As They Come, the debut collection by Angie Chau, gives us multiple perspectives on an extended family of Vietnamese immigrants, beginning five months after their arrival in San Francisco, as eight-year-old Elle recalls a Fourth of July during the summer all twelve of them lived in the same three-bedroom house. One of Elle’s aunts, Kim, becomes the focus of the next story, then her mother, Huong, then her father, Viet, and so on, before returning to the adult Elle in the final story. The shifting points of view give us access to a variety of experiences and insights into how we can still feel out of place even after years of living in the same location. In the story she’s chosen to write about for Beatrice‘s “Selling Shorts” series, Chau touches upon similar feelings of existential alienation and a child’s-eye view of an unsettling world all too close to home.

I relish personal stories. In life, I love listening to secrets, confessions, tidbits of gossip. In fifth grade I started a game with my two best friends called True Confessions. My best friend’s father was a jazz musician and had a sound proof studio behind the house. We stood on the make shift stage, turned on the microphone, and announced the one “true confession” that we would never admit out loud at school. The game didn’t last long. I don’t think my friends were as interested in this same sense of exposed purging. To this day, however, I am a good secret-keeper. Friends, neighbors, and coworkers always come back to tell me more.

In fiction, I crave the same kind of intimacy. I want it to be our world, yours and mine, alone. I want to feel like you trust me enough to reveal something untold to others, something you are uncomfortable about. And maybe through your courage, your vulnerability, through your telling of it, I get to admit things I didn’t have the words for before. I can acknowledge a shared fear or shame, I can ask questions I’ve never asked before.

A story that has inspired me is Sherman Alexie’s “Every Little Hurricane,” from The Lone Ranger and Tonto Fistfight in Heaven. Its technical brilliance, dark humor, and sweet sadness, distill a world in all its complexity into one night. Because I had never encountered Spokane Indians or any Native Americans in literary fiction, the story feels otherworldly, both refreshing and haunting. I was immediately struck by how these people were both absolutely foreign, yet somehow familiar.

The story begins when nine-year-old Victor is awakened in the middle of the night because his uncles are fighting at the “largest New Year’s party in tribal history.” The narrative is told from Victor’s tight third person point of view. In this case, the third person is the perfect choice; Victor’s sleepiness creates a dreamlike splendor as he stumbles through the chaos of strewn bodies and swinging fists and people either drinking, fucking, or fighting with one another. His youthful observations are matter of fact and stark. They resonate even deeper for their lack of flowery embellishment.

As Victor watches his uncles destroy each other in the snow, he hears somebody yell, “‘They’re going to kill each other.'” He realizes that, “Nobody disagreed and nobody moved to change the situation. Witnesses. They were all witnesses and nothing more. For hundreds of years, Indians were witnesses to crimes of an epic scale.” In one line he invokes his lineage and invites us to remember the past. Suddenly, the personal becomes political.

“He could see his uncles slugging each other with such force that they had to be in love. Strangers would never want to hurt each other that badly. But it was strangely quiet, like Victor was watching a television show with the volume turned all the way down.” The paradox is immediately set up. It’s a party but they’re fighting. They fight not because they hate each other but because they so deeply love each other. It is “strangely quiet” as the room holds the uneasy tension not of blaring noise but rather the TV turned all the way down. It is this continual contrast that creates the drama at the center of the story.

The tension mimics the storm brewing outside, “a hurricane dropped from the sky in 1976 [that] fell so hard on the Spokane Indian Reservation.” As you read on, the storm metaphors layer one on top of the other. The physical elements take over the entire story. The metaphor becomes so complete it takes on the feel of a prose poem. “The two Indians raged across the room at each other. One was tall and heavy, the other was short, muscular. High-pressure and low-pressure fronts…. One Indian killing another did not create a special kind of storm. This little kind of hurricane was generic. It didn’t even deserve a name…. In those nightmares, Victor felt his stomach ache with hunger. In fact, he felt his whole interior sway, nearly buckle then fall. Gravity. Nothing for dinner except sleep. Gale and unsteady barometer.” As a reader, you are swept up in the hurricane. You get lost in the fury and devastation at the heart of the Native American experience. It is the pain that is both nameable and unnamable akin to the “One molar [that]ached from cavity; [while] his chest throbbed with absence.”

I love the trappings of simplicity in this story despite its craftsmanship and artistry. The language is personal. Victor is constantly remembering dreams, dreams of drowning, dreams of hunger, dreams of a good song on a jukebox. In this way, the story looks intensely inward. At the same time, his supposedly sleepy observations present us with devastating images that we cannot turn away from. The story suddenly bears the weight of its socioeconomic skin. Victor’s innocence asks questions we cannot avoid nor answer. This is the story whispered in your ear between the sheets before dawn that doesn’t leave you for days or months or years, the kind of story that gets beneath your skin and lives with you, so intimate- it shapes the waking hours.

14 September 2010 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.