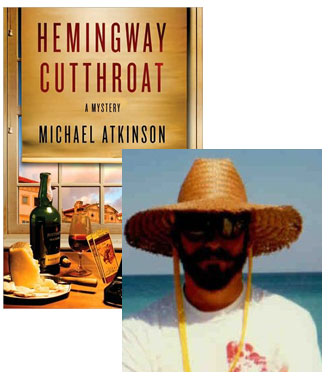

Michael Atkinson: Fictionalizing the True Gen

Hemingway Cutthroat is the second mystery novel from Michael Atkinson in which Ernest Hemingway learns of a murder and elects to pursue the truth behind the killing. The setting is Civil War-era Spain: John Dos Passos comes to Hemingway, who’s in Spain on a “discreet” rendezvous with Martha Gellhorn, and tells him that a mutual friend has vanished under mysterious circumstances, and nobody’s talking. It’s not like they’ll tell Hemingway anything, either, at least not at first… So what made Atkinson choose Hemingway for a protagonist? And how do you work with a “character” who’s so familiar to so many people?

It’s a proposition requiring a certain amount of ill-advised nerve—launching a mystery series using a spectacularly famous person as your protagonist sleuth. Double that if your celebrity is a world-renowned writer. There’s no limit to the amount of scat that could fly your way: fans irked, scholars betrayed, traditions subverted, biographers crossed. That fact hasn’t, of course, prevented it from being something of a trend, what with mystery series under way centering on Oscar Wilde, Edna Ferber, Edgar Allen Poe, and Mark Twain. (One shots include Sigmund Freud, H.G. Wells, Jane Austen, Lester Dent, Humphrey Bogart and… Elvis Presley!)

The genre seems to have been pioneered by one George Baxt, a gay pulp novelist and screenwriter from the midcentury, whose paperback series of Hollywood whodunits starred, for one novel each, Noel Coward, George Raft, Dorothy Parker, Tallulah Bankhead, Greta Garbo, Marlene Dietrich, and Alfred Hitchcock. It didn’t catch on then, but who knows, Baxt might be due for rediscovery.

The ground is, as they say, well-trammeled enough. It’s not difficult to fathom the allure of the celebrity-writer-sleuth genre-twist—the heady combustible brew formed by mixing genre violence and structure with the biography and personality of a beloved public artist. Who wouldn’t want in? My choice, which wasn’t a choice at all given the biographical real estate it bought me, was Ernest Hemingway. Search fruitlessly for another writer who has traveled as much, knew as many famous contemporaries, plunged headfirst into as many risk zones and war theaters, pissed as many people off, earned as many devoted friends, took as many women to bed, and still had psychosexual conflicts enough for a cast of Dostoyevsky characters and enough for it to kill him in the end. There’s so much seething stuff there it seemed hard to believe, once I researched it a bit, that no one had employed him as a fictional hero before.

What was probably more seductive about Hemingway was the simple fact of his renown—no other modern writer’s life is as well-known and well-documented. We all know this guy already (a poster of the famous black-&-white Yousef Karsh portrait of Hemingway was stapled, I remember, to the closet door of my fourth-grade classroom), whether we think he was a literary master, a paradigm of worldly machismo, a drunken lout, or a combination of all three. He’s so familiar it seemed that using his biography gave me a big leg up: Place him in Key West 1956 or Spain in 1937, and readers will be there in a shot, with no heavy lifting required. Trying to evoke the day-to-day life of, say, William Faulkner would be a trial—and depressing as hell. But Hemingway’s life is popular public domain and has been since before he died. (No writer may have ever had as many books written about him.) Readers of my books would be striding into comfortable, recognizable territory, as if they were visiting a tropical resort they’d been to years earlier and remember fondly.

But the matter of what my Hemingway would be like as a protagonist was still an issue. How comfortable would you be pinning this man to the wall? At best, at this distance, Hemingway is a volatile cocktail made up of macho rectitude, crazy egomania, suicidal depression, irrepressible life lust, devastating insecurity, wealth, ambition, restlessness, romanticism, alcohol in untold quantities, and a serious, life-poisoning injection of fame.

The mistake I didn’t want to make would be to have Hemingway resemble any of his own characters, or speak in the voice of his fiction. It’d be an easy trap to fall into, since we all have that voice in our heads. But it’d be illogical—Hemingway was notorious for dithering over his sentences, sitting at cafes for hours reworking a single page of story, painstakingly eliding words, etcetera. Nothing happened by accident in a Hemingway story, and the voice we know as Hemingwayesque did not come naturally to Hemingway—it was the by-product of hard work, work Hemingway himself admits to in every interview and in every chunk of A Moveable Feast.

As for the biographers’ Hemingway, or should I say, Hemingways, I largely gave them a pass. Suffice it to say that I’m suspicious of biographers, and of their agendas, which in the case of Hemingway have consisted of either lionizing him into a mythic figure or depicting him as the worst kind of boozy, amoral scumbag.

My contention going in was that he was neither of these things, nor necessarily a mix thereof. Hemingway was no paradigm of machismo or hard-drinking writerdom or struggling artiste-hood or literary celebrity or masculine piggery, or anything, really, at all. I know, because I’m a man, with scars and children and fuckups and dreams and bitternesses of my own, that he was not a paradigm of anything, he was just a man who wrote, a man who disappointed wives, a man lucky and unlucky enough to attract attention and become famous to a great many people he never knew. That’s all he was, or, truly, that’s all we know for sure. Anything else is spittle. The least you can do is respect the man as a man, just as you’d respect a living writer, or an unfamous or sober one, or your neighbor, or your reader, or yourself.

In other words, he had four full dimensions, and anyone who guesses they have them all pegged is a fool. I thought it’d be fair to cut across the cliches. Hemingway’s fiction isn’t funny, but I bet he was, what with that amount of booze and adventure and snappy company, and so he is in my books. And how could he not be self-aware? Everybody wants to be Hemingway, to some degree, and he knew it. His fictional vocabulary is sparse, but he was a heavily-read man, and so in my books the language that ambles through his skull and out of his mouth is varied, educated and profane both. He was a rotten husband in some ways, and an enviable one in others. He was perennially suicidal, too, but who said that meant he wasn’t great fun to be with? I looked at Hemingway’s timeline and saw one crazy attempt after another at having grand, ridiculous fun, probably, I reasoned, as a way to stave off the impulse to kill himself. Which he succeeded in doing for a good long time.

Certainly, there’s plenty of dark baggage dragging around behind the man, but I always saw him as an essentially comic figure—an irate mega-celebrity whose life never actually turns into the privileged, satisfying bliss he thought it would, despite every success. All of his contradictions feed this vision, as the cliches about him do not. But perhaps most of all, my Hemingway knows the masculine principles he holds in his heart don’t really apply to life in the real world—and don’t mix well with wives—but he also finds out that sometimes they do. That is perhaps my ace in the hole—seeing Hemingway’s beleaguered ideas of nobility and machismo and justice as his motivating reason, when he’s confronted with a murder or victimizing crime, to actually step in and set things right. Hemingway can be a selfish bastard, like us all. But if things are not right, my Hemingway, with nothing holding him back from taking matters into his own hands, can decide to fix the world. And if it runs the risk of getting him killed in the process, well, he’s been meaning to get around to that anyway.

9 August 2010 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.