Read This: Zero History

Usually, when I review for Shelf Awareness, my focus is on science fiction and fantasy novels, but when a galley of the new William Gibson novel, Zero History, I took advantage of Gibson’s SF background to call dibs, and my review appeared yesterday. I’ve been a fan of Gibson since stumbling onto Neuromancer as a junior high school student in the mid-1980s, although my fandom evolved to have some reservations; in the 1990s, for example, as much as I loved all the background details of the worlds he was creating, I felt like Gibson had a problem with endings, a tendency to hustle things along and wrap things up when the story reached a certain length. When I read Pattern Recognition, the first of his novels to be set in the contemporary/”real” world, I felt like he’d finally licked that problem, and I was deeply impressed with the ways he was redefining the thriller to reflect the political, economic, and cultural shakeups of the early 21st century in that book and its followup, Spook Country.

Usually, when I review for Shelf Awareness, my focus is on science fiction and fantasy novels, but when a galley of the new William Gibson novel, Zero History, I took advantage of Gibson’s SF background to call dibs, and my review appeared yesterday. I’ve been a fan of Gibson since stumbling onto Neuromancer as a junior high school student in the mid-1980s, although my fandom evolved to have some reservations; in the 1990s, for example, as much as I loved all the background details of the worlds he was creating, I felt like Gibson had a problem with endings, a tendency to hustle things along and wrap things up when the story reached a certain length. When I read Pattern Recognition, the first of his novels to be set in the contemporary/”real” world, I felt like he’d finally licked that problem, and I was deeply impressed with the ways he was redefining the thriller to reflect the political, economic, and cultural shakeups of the early 21st century in that book and its followup, Spook Country.

I still stand by that, and I think it applies to Zero History as well, but it’s interesting, having re-read the first two novels immediately after reading this most recent one, to see if I’d found all the right connections, to see how each of them is built on the same basic framework, which I discuss in the review:

“Hubertus Bigend, a Belgian multibillionaire who owns a mysterious media/advertising company called Blue Ant, … has emerged as a not entirely unsympathetic iteration on what a Bond villain might look like in the real world. When you read the novels in quick succession, you realize they all follow the same narrative template: Bigend hires a woman to investigate a subcultural phenomenon; somewhere along the line, spies—both active and retired—involve themselves in the events.”

Maybe Bigend’s comparative scarcity throughout the trilogy—he’s a lot more than a secondary character, but he’s never the primary character, if that makes sense—makes him more intriguing to readers (or at least a reader like me). Gibson clearly seems fascinated with the character both as a character and as a powerful force; I chose my “Bond villain” analogy deliberately—,and, in retrospect, almost certainly influenced by an essay Charlie Stross appended to his novel The Jennifer Morgue, “The Golden Age of Spying,” in which he re-imagines SMERSH as simply a multinational corporation ahead of its time: “venture capitalists investing in disruptive new technologies, in other words—commercial space travel, nuclear power, antibiotics. Not some half-baked terrorist organization!” And though there are a few aspects to Hubertus Bigend and his schemes that require a bit more suspension of disbelief than usual, I think one of Gibson’s biggest accomplishments in this series is Bigend’s ultimate plausibility—it’s not so very hard to believe somebody like him might exist out there (a Richard Branson who’d taken a few different turns along the way, perhaps?). You may not want to read all three novels too closely together, because of the plot similarities, but it would definitely be worth your time to familiarize yourself with the world Gibson has been describing in them.

31 August 2010 | read this |

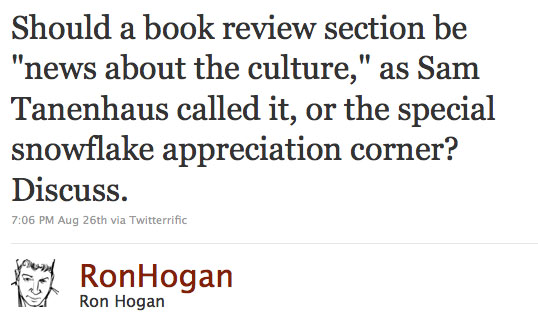

Franzenfreude Is Only the Tip of the Iceberg

Jonathan Franzen’s new novel, Freedom, isn’t even out yet, and already it’s become one of the most talked-about novels of the year—although, if truth be told, for the last week people have actually been talking more about how much people have been talking about Freedom than they’ve been talking about the novel itself. Let me explain: Jennifer Weiner, who also has a new novel out this summer (Fly Away Home), pointed out that the folks who run the book coverage at The New York Times sure do love them some Franzen, based on the number of articles they’ve written about him and his book, and she noted that this attention (which she called “Franzenfreude”) is just the latest manifestation of the Times tendency to dwell obsessively on Great White Male Novelists—I can’t recall offhand if she used specific examples, but she could certainly have cited the ways in which, after the publication of I Am Charlotte Simmons, the Times became, as I put it, “the newspaper that cried Wolfe,” or their fixation on John Updike after the publication of Terrorist, as examples. Soon after Weiner’s remarks, Jodi Picoult reinforced the message with a tweet that said, in part: “Would love to see the NYT rave about authors who aren’t white male literary darlings.”

It’s not surprising that much of the media coverage has tried to frame the resulting argument as “women who write bestselling commercial fiction take out their resentment over a lack of critical respectability on a literary man,” but there’s a lot more to this situation than mere personality conflict. Weiner and Picoult, among others, are giving us a valuable critique of a serious problem with the way the Times—and, frankly, most of the so-called literary establishment—treats contemporary fiction. Which is to say: They ignore most of it, and when it comes to the narrow bandwidth of literature they do cover, their performance is underwhelming, “not only meager but shockingly mediocre,” as former LA Times Book Review director Steve Wasserman said three years ago. And it hasn’t gotten any better since then, leaving us with what Jennifer Weiner describes as “a disease that’s rotting the relationship between readers and reviewers.”

30 August 2010 | theory |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.