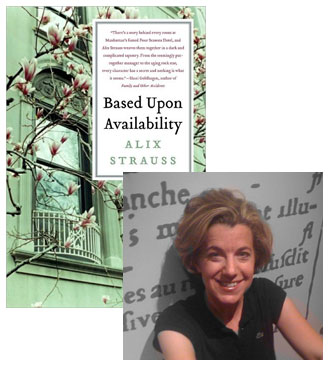

Alix Strauss: The Luxury Hotel as Literary Platform

It’d been nearly a year since the last time I saw Alix Strauss, which had been the launch party for Death Becomes Them, so I was delighted to meet up with her recently to chat about her second novel, Based Upon Availability—which is a bit like her debut, The Joy of Funerals, only “run backwards” as Alix puts it; where that book told the stories of several women and then tied up all the narrative threads with one longer story at the end, this one starts out with the story of Morgan, a manager at the Four Seasons in Manhattan, as she encounters a batch of women through the course of her work, then backtracks to explore what brought each of those characters to the hotel.

“I was fascinated by hotels and the idea of anonymity,” Alix said of the novel’s origins. “I love the idea that you could be anybody from anywhere, check into a hotel, and then the minute you check out, that room is wiped clean and any presence of you is erased.” Why the Four Seasons? “It’s signature, it’s branded, everybody understands it—there was that instant recognition of the hotel, but also an instant recognition of the kind of person who stays there.” For research, she spent a lot of time in the hotel’s lobby and restaurant, and relied on her previous experiences writing about it in a journalistic capacity, then spent a night in one of the rooms, “channeling” one of her multiple protagonists—in this case, a middle-aged rock star whose publicist has checked her into the hotel to go through withdrawal. “I ran around naked, had an unlit cigarette dangling from my lips, slapped on some fake tattoos, brought a bottle of vodka with me,” she recalled. “I ended up laying on the bathroom floor like my character does, trying to induce this psychotic lapse into inebriation and lunacy.”

So what does the Four Seasons think of its latest literary recognition? “I got a call from the PR person, who I’ve known for a number of years,” Alix told me. “She said, ‘We can’t stop hearing about this novel, can we get a copy?’ And that was a couple of weeks before it came out. I’ve not heard from her since… but I hope that they embrace it in the sense that it was meant, which was as a huge tribute to the hotel. Yes there are a lot of shenanigans that go on, but what hotel doesn’t have that?” In the meantime, she’s been doing readings in a number of other hotels in Manhattan and other cities; tomorrow night (July 21), for example, she’ll be at the Liberty Hotel in Boston.

20 July 2010 | interviews |

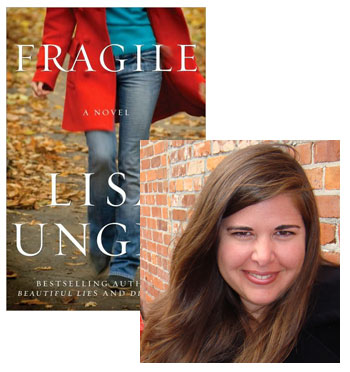

Lisa Unger & The Heart of the Story

If you’ve been reading Beatrice long enough, you’ve probably figured out that I don’t care too much about genre labels—as far as fiction is concerned, it’s all just one big stack of stories to me, and what matters is: Is it told well? Lisa Unger’s essay about the origins of her new novel, Fragile, speaks to the arbitrary barriers publishers, bookstores, and critics use to keep some books separate from others, but it’s also about how stories can come to writers who aren’t quite ready to tell them, and what happens when those stories won’t go away.

Once upon a time, an editor I had respected and from whom I had learned quite a bit suggested, as she turned down my novel, that I make some decisions about myself. In fact, what she said precisely was, “Lisa, you have to decide what you are. Are you a literary writer? Or are you a mystery writer?”

I didn’t really consider myself either one of those things; I had never endeavored to define myself as a writer of anything but story. When I began my first novel at the age of nineteen, I didn’t sit down to write a mystery novel or a literary novel. I was just writing what I wanted to write… and that was a story about a troubled woman who had chosen a dark profession to try to order the chaos she perceived in her life and in the world. There was a psychic healer, a former FBI agent, and a high body count. So, yes, I supposed when the book was done, it was in fact a mystery—or a maybe a thriller. Possibly, it was crime fiction. The point is: When my fingers were at the keyboard, the question of what space it would occupy on the bookshelf simply never occurred.

It took me ten years to finish and finally publish that novel, and then I published three more “mystery novels” under my maiden name Lisa Miscione. They were small books, based on an idea that I had when I was really too young to be writing books. Though they will always occupy a special place in my heart, I consider them the place where I cut my teeth, honed my craft and became a better writer.

Now, with eight novels on the shelves, one about to be published, and my tenth nearing completion, I still don’t give too much thought to who I am as a writer, what kind of books I’m writing. I am published in a place where people support the evolution of my fiction. At Shaye Areheart Books, I have never been asked to define myself or to change how and what I write. So when my wonderful editor said how different she thought Fragile was, her statement wasn’t followed (thankfully) by “We can’t publish this.” Still, the idea that the novel was not like what came before it caught me off guard. Wasn’t it? It didn’t feel different when I was writing it. Though I did have a sense that it was heftier in some way, harder to manage.

19 July 2010 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.