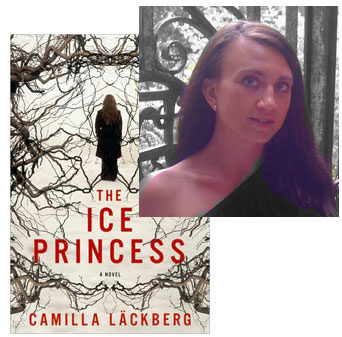

Camilla Lackberg & The Creative Writing Assignment that Launched a Bestselling Crime Series

“I was probably the unhappiest economist in Sweden,” Camilla Läckberg told me, recalling her life before she began writing some of that nation’s most popular crime novels. She’d always wanted to be a writer, she explained, “and one day my mother and my now-ex-husband got sick of hearing me talk about it, so they signed me up for a writing course… Before that, I just couldn’t believe how you would form all those words together; taking the course, the idea became more down-to-earth. It became a craft, a skill.” For one of the class writing assignments, Läckberg was told to write the first chapter of a book: “I didn’t have the idea before the course,” she emphasized. “It wasn’t something that had been with me for years.” But once the initial concept of a respected biographer who returns to her hometown after her parents’ death and soon discovers her childhood friend has been murdered was set down, it stuck with her, and two-and-a-half years later, she had finished The Ice Princess.

“I was probably the unhappiest economist in Sweden,” Camilla Läckberg told me, recalling her life before she began writing some of that nation’s most popular crime novels. She’d always wanted to be a writer, she explained, “and one day my mother and my now-ex-husband got sick of hearing me talk about it, so they signed me up for a writing course… Before that, I just couldn’t believe how you would form all those words together; taking the course, the idea became more down-to-earth. It became a craft, a skill.” For one of the class writing assignments, Läckberg was told to write the first chapter of a book: “I didn’t have the idea before the course,” she emphasized. “It wasn’t something that had been with me for years.” But once the initial concept of a respected biographer who returns to her hometown after her parents’ death and soon discovers her childhood friend has been murdered was set down, it stuck with her, and two-and-a-half years later, she had finished The Ice Princess.

Her debut novel landed with a small publisher and sold 3,000 copies—“not bad for a Swedish debutante,” she reflected—but not enough to quit her job as an economist for a cell phone company, either. So she found an agent who was able to place the sequel with a larger house; that book sold 30,000 copies, and by the fifth volume in the series, she was selling 200,000 copies in Sweden alone. (It helped that she’d also had two maternity leaves, during which she wrote two more books, those sales building up as her former career approached its conclusion.) The series now stands at seven books in Sweden, as The Ice Princess finally arrives to this country in an English-language edition this summer. Pegasus is publishing the first three books in hardcover, but less than a week after I met Läckberg during her visit to New York City for Thrillerfest, Free Press and Pocket Books announced they’d bought up the paperback rights to the initial triptych and would publish them in trade and mass market editions simultaneously.

“I always knew I wanted to write a series,” Läckberg said, “I love reading them, and as a writer it’s a wonderful opportunity to develop characters. I’ve been living with Erica and Patrik [the writer-turned-sleuth and her friend on the local police force] for so long, they’re like my friends now, I know them that well.” Because she conducted the interview in fluent English, I asked if she had any hand in the translation of her novels for this market. “I don’t have the rhythm for the language the way a native would,” she explained. “I don’t hear the fine tuning in the melodies of the language. And by the time I’ve finished a book,” she laughed, “I’ve proofread it about ten times already.” She is, however, on hand to help her translators sort out unfamiliar cultural concepts—which prompted me to ask about the various authors whose biographies Erica is said to have written. They’re real? I asked. Oh yes; “they’re the writers they force you to read in school because they’re Swedish classics,” Läckberg smiled.

22 July 2010 | interviews |

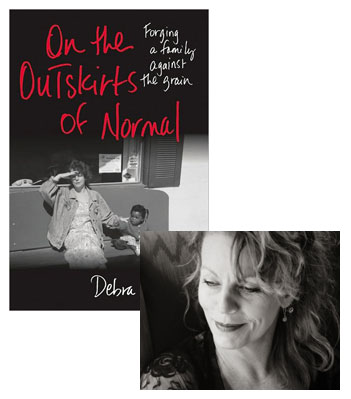

Debra Monroe: Choosing Real Life over Easy Myths

When SMU decided to suspend operations of its university press earlier this year, I tried to put a spotlight on some of the remarkable work that press had done publishing short stories, but that’s not all they do. Debra Monroe‘s memoir, On the Outskirts of Normal, is that rare university press title that makes a big splash in the mainstream book reviewing media, including a recommendation from Oprah magazine. Monroe’s voice is a storytelling natural, conveying her experiences not in the order in which they happened but in a way that makes the most emotional sense. But it almost didn’t turn out that way.

At one point, Monroe took an agent’s suggestion and hired a freelance editor to impose a tighter chronological order on the story of a single white woman adopting a black child. “I would never have agreed at any other time in my life, because I don’t spend money that way,” she told me, but an editor at a large publisher had committed to taking another look at the manuscript if it were revised into a slightly more conventional form. “At the time, I was selling my house, and decisions amounting to a few thousands dollars were going on daily… Well, I did it, but pulled out when it was getting too expensive. (Plus, the freelance editor had started in with the New York-centric conversations about toothless racists in the Texas countryside and the ‘age of Obama’ crap.)” The problem was that the new, linear narrative was, in Monroe’s own estimation, discursive and rambling. “The central conflict was lost because the central conflict had been not-understanding-my-fears (life as chaos) vs understanding-my-fears (life as a story),” she recalled. “Telling the story as the search for meaning required some chronological manipulation.” The agent who’d recommended the freelance editor in the first place declared the results boring, then suggested Monroe juice up the story by emphasizing the racial elements.

So Monroe walked, and when she showed her original manuscript to Kathryn Lang at SMU, “she kept the organization as it was, with the central conflict between life-as-a-series-of-accidents and life-as-a-tale-that-means-something. We worked a bit on more ‘glue’ for the structure, but stayed true to it.” As Monroe explains in this essay, her memoir isn’t a story about transracial adoption, but one in which that experience shapes a much broader transformation.

Fact: My daughter is black, and I’m white. I adopted her when Angelina Jolie was a fashion model, not a movie star or UN ambassador or adoptive mother. The Multiethnic Placement Act had just passed, and ours was the first transracial adoption my agency handled. I was a novelist. I used the advance on my third book to pay my adoption fees. Then I started writing nonfiction. I’d endured a crisis or two. I wanted to revisit these years—certain moments incandescent, others blurry and obscured—and find a plot, not invent one. Love. Death. Illness. Ordinary trouble. I write books because of the way I read: I want my books to get some reader through one of those dark nights of self-doubt.

I’d published previous books with both small and large presses. In my experience, small presses provide the most intelligent, passionate editing on the planet, but they have few resources for distribution and publicity. Because large presses have more of the latter, they deliver more readers. So I hoped to sell my book to a large press. People really liked the concept: white woman, black child, small Texas town. I felt racial and geographical assumptions falling into place. During long phone calls and protracted emails, the phrase “the age of Obama” came up. So did market exigencies.

But the advice that stopped me in my tracks was to emphasize race more; an agent described inconceivably huge advances if I would. But how? We encountered worse problems with racism and. . . I taught the town a lesson? I overcame racism? The needle on my moral compass went haywire.

21 July 2010 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.