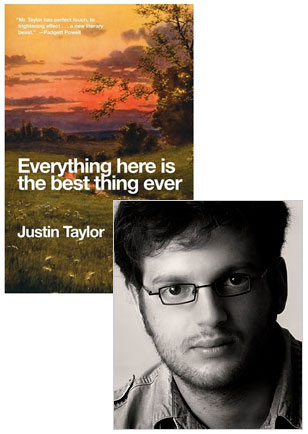

What Justin Taylor’s Learned from “The Crazy Thought”

I’m not a bad son. Only prodigal,” says the narrator of one of the stories in Justin Taylor’s debut collection, Everything here is the best thing ever, and it’s a sentiment many of his characters could share. Sure, on the surface, they look like screwups, and let’s face it some of them are a bit screwed up, but Taylor breaks past the surfaces and lets us into their lives, sometimes (as in “In My Heart I Am Already Gone” or “The New Life”) showing how mental and emotional blind spots can steer us down a path with devastating consequence. For his “Selling Shorts” essay, Taylor has chosen a similar story, the impact of which he himself didn’t quite recognize at first.

One of my favorite story collections is The Wonders of the Invisible World, by my former teacher, David Gates. The ten stories in David’s book are riveting and dark. Their incisiveness—not for nothing from the Latin, to carve—is downright scary; they are brutal and wise. The protagonists of these stories are old and young, gay and straight, women and men; and yet, they all tend to share certain qualities: a level of sophistication (high), education (ditto), attitude (bad), and class (white-collar middle, striving for upper). The result is a very strange and exciting paradox: a group of discontinuous cross-cuts that somehow adds up to a panorama.

Of the ten stories in Wonders, the one I return to most frequently is the first one, “The Bad Thing,” which I’ve re-read (and also taught) enough times now that I’d like to try and quote the opening from memory: “He has never hit me, and only once or twice in our two years has he raised his voice in anger. Even in bed Steven is gentle. To a fault. Why, then, am I wary of him?” But I don’t want to talk about “The Bad Thing.” I want to tell you about a story called “The Crazy Thought,” a sly devastator, and my nomination for the book’s outstanding deep cut.

The things that make “The Crazy Thought” such a marvel are not elusive, exactly, but they are relatively easy to miss. I confess that the story didn’t make much of an impression on me the first few times around. In fact, I had forgotten about it entirely until I pulled Wonders off the shelf to double-check my quoting-from-memory of the opening of “The Bad Thing,” which is the story I thought I was going to be writing about when I started. (Oh, and if you were wondering, my attempt at recitation was close, but not quite cigar-worthy. The quote given above is the amended, which is to say the correct version.)

Flipping idly around, I stumbled onto “The Crazy Thought,” and for whatever reason decided to stop what I was doing and give it a re-read. (Perhaps I was drawn in by the slightly bizarre, though arguably easier-to-memorize opening line: “The year was round, a millstone turning slowly clockwise, and even on this Friday afternoon in August, Faye could feel it moving down toward Christmas.”) In any case, true to its title, I now can’t get “The Crazy Thought” out of my head.

If you were trying to summarize this story, you might say it is about two married couples: Faye and Paul, and Karen and Allen. The latter pair are coming in from the city to spend a weekend in the country with the former. Karen and Faye are sisters who haven’t seen each other in a while—in fact, Faye and Paul have never met Allen. See, Faye and Paul left behind all that big-city bullshit a few years ago, to live the good, simple life in rural Vermont. She took a job with a local newspaper and he was going to write his novel; only “the plan” didn’t quite work out. Now she’s a full-time housewife and he works on a road crew, the salary for which is not cutting it lately (his novel, needless to say, is not getting written). So Faye and Paul are on the rocks (as in, vodka on the rocks) but they’re going to try and put up a decent front for Karen and Allen, and the story is “about” that effort’s success and/or failure.

But here’s the thing. You don’t get any of that information from the first paragraph of the story, which is entirely concerned with Faye’s memories of a first husband named Ben, and a pregnancy they aborted around the same time the marriage broke up. If I asked you to read just the first paragraph, and then predict what the story is about, you might tell me it was a story about a wounded woman, alone, trying (maybe not all that hard) to keep the broken fragments of her life from slipping through her fingers for good.

But now here’s what’s really the thing. The person who predicted what the story would be about is actually much closer to the mark than the person who summarized it. “The Crazy Thought” is not a story about marriages, or couples, or sisters, or even, in the book jacket’s own eloquent phrasing, “urbanism [in] uneasy conflict with a dream of rural happiness.” The story has all those things in it, sure, but at the end of the day it’s not about them. It is a story about the utterly solipsistic Faye, who is never more alone than when in the company of her husband and sister and brother-in-law. She is only stirred to something like life when actually (as opposed to emotionally) alone, and therefore free to devote her full attention to mourning the ghosts of Ben and their averted child.

Gates, probably the living master of the close-third person narrative (cf. his second novel, Preston Falls), ensconces us immediately and completely in Faye’s perspective. We feel as if we’re breathing down Faye’s neck, or perhaps riding shotgun in her careening mind. The extent of Faye’s self-deceptions are revealed in vivid flashes, glimpsed as the other characters react to things she’s said or done, but because you’re with Faye and not them, it doesn’t occur to either of you until later that maybe they’re onto something, and she’s the one who’s off. (Though it must be said in Faye’s defense that the rest of them are hardly model citizens—the bulk, but not the balance, of her problems are self-generated.)

Early on in the story, Faye considers the origins of a common turn of phrase and determines that “[t]his was one of the many things that flew apart if you looked too closely.” This line is the secret key to Faye’s character, not least because she is on the one hand smart enough to see this fact plain, while on the other hand unable to see that she’s talking about herself. The Wonders of the Invisible World, meanwhile, does more than merely hold together. Every story in it rewards the considerate reader with truths that feel at once unexpected and inevitable: not revelations but recognitions, drawn out of the invisible world of the—take your pick—heart, spirit, psyche, and made manifest in this world, where for better or worse we are stuck.

28 July 2010 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.