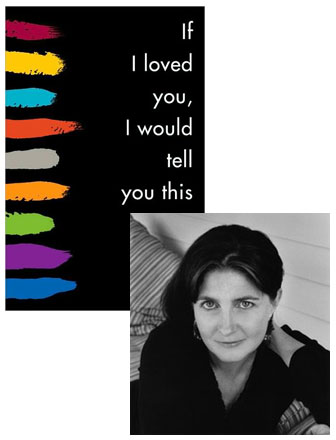

Robin Black & the Heart of “A Stone Woman”

In her guest essay, Robin Black recalls an early teacher’s description of her stories as “domestic angst,” and how she took it at the time as a minimization of her work. But when you read If I Loved You, I Would Tell You This, you come to both the accuracy of that brief phrase and the strengths it implies. Many of Black’s stories test the stress points of family relationships—husbands and wives, parents and children, brothers and sisters—to the extreme, exerting pressures from within and without, and the results are emotionally raw and all too plausible. But, as she explains here, Black found inspiration for the persuasive realism of her most powerful stories in a fantastical source…

“At first, she did not think of stones.” So begins A.S. Byatt’s “A Stone Woman,” the story of a middle-aged daughter whose grief over her mother’s death transforms her into a being of myriad crystals, taking her from animal to mineral. From my very earliest reading, “A Stone Woman” entered my consciousness like news I had been waiting to hear. It became mine, a touchstone of sorts, in the way certain stories do for us all, which initially puzzled me because I haven’t ever been particularly attracted to magical stories. In fact, it’s fair to say that pretty much as soon as trees start talking or shoes begin walking on their own, I’m apt to tune out, more pushed away than swept away. Yet this story of transformation, with its evocation of Icelandic mythology and utter disregard for the prosaic rules of reality, seemed to have something, something essential, to tell me about my own work.

Trying to describe why you’re in love with a story is like trying to describe why you’re in love with anything, or anyone. In the end—says the woman who just claimed she doesn’t much like magic—there’s a magic that can’t and arguably shouldn’t be dissected. But maybe at the heart of all romances is the sensation of being able to be oneself, the vision of being loved as the person you think you are.

When I first read “A Stone Woman,” I was in the later phase of my MFA work and I was beginning to panic moving out of the student role. It went beyond a lack of confidence in the quality of my work. I felt a reluctance to embrace it, to accept not its quality so much as its nature. I was—it seemed—drawn to depictions of loss and its aftermath, including grief, but also including renewed hope, steeled determination. My landscape was a decidedly interior one, emotional and also cerebral—by which I don’t mean smart, just that I liked writing about thought processes. And, as I had been a full-time mother since the age of twenty-five, nearly two decades at that point, my work tended to focus on family relationships and unfold in homes—I was writing what I knew. One teacher had already brought me to tears by describing my stories as depictions of “domestic angst” a phrase that seemed at the time—unintentionally, I’m sure—to diminish multiple aspects of the work; subject matter, setting, scope, scale, originality and potential for genuine importance.

As is probably obvious, fueling my disenchantment with my work was a kind of anxiety of womanhood. I feared the Women’s Fiction shelf, the section I pictured wedged between Romance and Self Help, feared that by virtue of my subject matter and the context in which I tended to explore it, in combination with the fact that I actually am a woman—how many men are ever termed authors of domestic fiction?—my work would never be viewed as actual literary fiction, the kind that doesn’t come with a gender designation; the kind men write.

And then along came A.S. Byatt’s beautiful and brutal story about the oldest subject in the world, the weariest of all the weary scenarios of domestic angst, the someone’s-mother-died-and-she’s-miserable story. Wholly re-imagined, heartbreaking and unsentimental. Familiar and original. Unfamiliar and recognizable. An anthem to the truth, which is that no subject is ever exhausted or inherently small. And the story kicked the ass of anything I had read in a very long time. Of course, it also obliterated anything I had written too, but that was fine. I didn’t mind that a bit.

What I needed at that point wasn’t flattery or confidence in pages I had already composed. What I needed were goals and examples. What I needed was a woman’s voice in my ear, a rather severe one as it turned out, reminding me of what absolute rubbish it is that domestic stories are somehow inherently lesser, suitable to be read by one gender and not the other. What I needed was some help with my own transformation, some courage about doing what I imagine every writer must eventually do: dive ever deeper into her obsessions, tune out the static that distracts her from that task and from that joy. In other words, be herself.

26 July 2010 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.