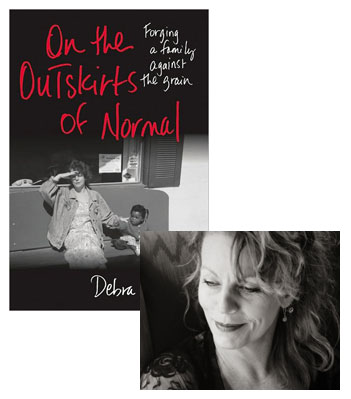

Debra Monroe: Choosing Real Life over Easy Myths

When SMU decided to suspend operations of its university press earlier this year, I tried to put a spotlight on some of the remarkable work that press had done publishing short stories, but that’s not all they do. Debra Monroe‘s memoir, On the Outskirts of Normal, is that rare university press title that makes a big splash in the mainstream book reviewing media, including a recommendation from Oprah magazine. Monroe’s voice is a storytelling natural, conveying her experiences not in the order in which they happened but in a way that makes the most emotional sense. But it almost didn’t turn out that way.

At one point, Monroe took an agent’s suggestion and hired a freelance editor to impose a tighter chronological order on the story of a single white woman adopting a black child. “I would never have agreed at any other time in my life, because I don’t spend money that way,” she told me, but an editor at a large publisher had committed to taking another look at the manuscript if it were revised into a slightly more conventional form. “At the time, I was selling my house, and decisions amounting to a few thousands dollars were going on daily… Well, I did it, but pulled out when it was getting too expensive. (Plus, the freelance editor had started in with the New York-centric conversations about toothless racists in the Texas countryside and the ‘age of Obama’ crap.)” The problem was that the new, linear narrative was, in Monroe’s own estimation, discursive and rambling. “The central conflict was lost because the central conflict had been not-understanding-my-fears (life as chaos) vs understanding-my-fears (life as a story),” she recalled. “Telling the story as the search for meaning required some chronological manipulation.” The agent who’d recommended the freelance editor in the first place declared the results boring, then suggested Monroe juice up the story by emphasizing the racial elements.

So Monroe walked, and when she showed her original manuscript to Kathryn Lang at SMU, “she kept the organization as it was, with the central conflict between life-as-a-series-of-accidents and life-as-a-tale-that-means-something. We worked a bit on more ‘glue’ for the structure, but stayed true to it.” As Monroe explains in this essay, her memoir isn’t a story about transracial adoption, but one in which that experience shapes a much broader transformation.

Fact: My daughter is black, and I’m white. I adopted her when Angelina Jolie was a fashion model, not a movie star or UN ambassador or adoptive mother. The Multiethnic Placement Act had just passed, and ours was the first transracial adoption my agency handled. I was a novelist. I used the advance on my third book to pay my adoption fees. Then I started writing nonfiction. I’d endured a crisis or two. I wanted to revisit these years—certain moments incandescent, others blurry and obscured—and find a plot, not invent one. Love. Death. Illness. Ordinary trouble. I write books because of the way I read: I want my books to get some reader through one of those dark nights of self-doubt.

I’d published previous books with both small and large presses. In my experience, small presses provide the most intelligent, passionate editing on the planet, but they have few resources for distribution and publicity. Because large presses have more of the latter, they deliver more readers. So I hoped to sell my book to a large press. People really liked the concept: white woman, black child, small Texas town. I felt racial and geographical assumptions falling into place. During long phone calls and protracted emails, the phrase “the age of Obama” came up. So did market exigencies.

But the advice that stopped me in my tracks was to emphasize race more; an agent described inconceivably huge advances if I would. But how? We encountered worse problems with racism and. . . I taught the town a lesson? I overcame racism? The needle on my moral compass went haywire.

Though I’d fielded plenty of awkward questions, I’d met only a few scary bigots. The constant conversations about race were instead confused, confusing. I said, “I’ve spent the last years deemphasizing race.” The agent said, “Look, motherhood itself isn’t interesting. It’s like this—you’re not racist, but you meet other people who are. Think of yourself as the everywoman’s Angelina Jolie.”

I know that, combined, my daughter’s race and mine attract attention. And attention is a market commodity. I also know that, in our semantically cautious times, there are only a few pre-approved stories white people will tell about race. (Historical: We used to be racist. Feel-good: We’re not racist. Scolding: Look at those racists over there.) But life is complex. People’s curiosity was natural, given the time and place. Most of the curiosity was friendly, if disruptive, and I learned to extemporize, to answer questions tactfully, because my daughter was listening and what I said affected her well-being.

Facile ways of writing about race imply that all the uneasiness is behind us or nowhere near. In fact, it’s everywhere and tacit. My defenses against it, defenses I modeled for my daughter, are tacit. I retrieved her from playing at a neighbor’s, where grandkids visited. “How’d she do?” I asked. I meant did she say please and thank you. My neighbor said, “Like she had blond hair and blue eyes.” I thought: How do I answer that? Should she go back tomorrow? The grandkids were fun, my daughter reported. As for rare, overt slurs, I told her, in age-appropriate language, that some people don’t like people based on skin color, and we don’t think like that, and we don’t like people who do. God doesn’t either, I added. Or Santa Claus. I didn’t soapbox to strangers. I didn’t take a stand for the public good. But I kept my daughter from being other people’s object lesson.

The book I was asked to write was a book about a woman who saw motherhood as a statement. The book I wrote was about making my daughter happy, prepared. I didn’t set out to prove I believe in social justice. One mother and daughter, or one zippy comeback, won’t change hundreds of years of history. Coming to terms with history in small, recurrent moments of understanding—sometimes initiated by comments from strangers, sometimes by my daughter’s precocious reaction—was a subplot, never my plot. So I sold my book to a small press where I got the most intelligent, passionate editing on the planet.

Now that the book has gotten national coverage, I note that it’s the racial and geographical assumptions I’d fought hard against in the first place that are getting the book noticed and reviewed in big venues. But it’s my insistence on complexity—seeing race as a fact of life, not the fact of life—that’s helped the book stand up to scrutiny. Reviewers and ordinary readers too express pleasure, even relief, that race is a salient fact in an otherwise universal story about the leap of faith we all take in loving our children, and that the book depicts the messiness of life, its lack of easy answers.

21 July 2010 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.