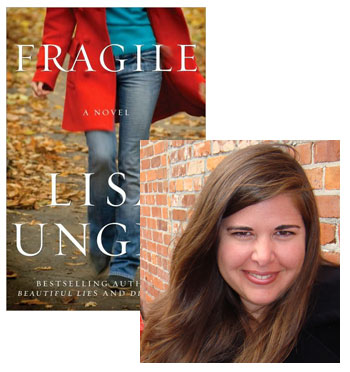

Lisa Unger & The Heart of the Story

If you’ve been reading Beatrice long enough, you’ve probably figured out that I don’t care too much about genre labels—as far as fiction is concerned, it’s all just one big stack of stories to me, and what matters is: Is it told well? Lisa Unger’s essay about the origins of her new novel, Fragile, speaks to the arbitrary barriers publishers, bookstores, and critics use to keep some books separate from others, but it’s also about how stories can come to writers who aren’t quite ready to tell them, and what happens when those stories won’t go away.

Once upon a time, an editor I had respected and from whom I had learned quite a bit suggested, as she turned down my novel, that I make some decisions about myself. In fact, what she said precisely was, “Lisa, you have to decide what you are. Are you a literary writer? Or are you a mystery writer?”

I didn’t really consider myself either one of those things; I had never endeavored to define myself as a writer of anything but story. When I began my first novel at the age of nineteen, I didn’t sit down to write a mystery novel or a literary novel. I was just writing what I wanted to write… and that was a story about a troubled woman who had chosen a dark profession to try to order the chaos she perceived in her life and in the world. There was a psychic healer, a former FBI agent, and a high body count. So, yes, I supposed when the book was done, it was in fact a mystery—or a maybe a thriller. Possibly, it was crime fiction. The point is: When my fingers were at the keyboard, the question of what space it would occupy on the bookshelf simply never occurred.

It took me ten years to finish and finally publish that novel, and then I published three more “mystery novels” under my maiden name Lisa Miscione. They were small books, based on an idea that I had when I was really too young to be writing books. Though they will always occupy a special place in my heart, I consider them the place where I cut my teeth, honed my craft and became a better writer.

Now, with eight novels on the shelves, one about to be published, and my tenth nearing completion, I still don’t give too much thought to who I am as a writer, what kind of books I’m writing. I am published in a place where people support the evolution of my fiction. At Shaye Areheart Books, I have never been asked to define myself or to change how and what I write. So when my wonderful editor said how different she thought Fragile was, her statement wasn’t followed (thankfully) by “We can’t publish this.” Still, the idea that the novel was not like what came before it caught me off guard. Wasn’t it? It didn’t feel different when I was writing it. Though I did have a sense that it was heftier in some way, harder to manage.

This story has tried to find its way out in various partials over the years. Always with different voices and never quite succeeding to resolve itself. I was surprised when it surfaced in Fragile. And in writing this book I learned something truly interesting: One can have ambitions to write a story but not have the talent or the craft to tell it well. It took the writing of eight novels before I had the skills necessary to tell the story, to write the kind of book that had simmering for decades.

Of course, also, the subject matter of this novel was uniquely personal, based loosely on an event in the town where I grew up. A girl I knew, someone who attended my high school, was abducted and murdered. We were teenagers, growing up in a quiet, idyllic suburban town, and her gruesome death changed forever how I saw the world; though I am not sure I was aware of this until recently. I didn’t realize how it had stayed with me until I was metabolizing it on the page. This may be another reason it took so long for the story to find its way, to find the voices it needed to say what had to be said.

The idea that Fragile is a departure for me—a move away from one type of writing and into another, seems a little strange. On the other hand, how could it not be different? How can every book not be different than the one that came before? I’m different—every year older with new experiences and (hopefully) more wisdom and insight into people and the world around me. How could the book I’m writing at thirty or forty not be different from the one I was writing at nineteen? As far as I’m concerned, it had damn well better be.

I know there can be some snobbery in the industry. If you’re writing mystery or thriller or crime fiction, there’s a sense that you’re not writing as well as those who are writing “literary” or “general” fiction. But we have only to look to writers like Laura Lippman, Ruth Rendell, Dennis Lehane, Kate Atkinson and George Pelecanos to know better. I’d go so far as to say that some of the best people writing today are writing in crime fiction. And I think if you asked most writers what kind of books they write, most of them would pause. The answer they’d give might not be their own, or one that felt as if it fit completely. I certainly don’t claim to know the answer when I’m asked. I always nicely say, “Maybe you should read my books and tell me what you think they are.”

19 July 2010 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.