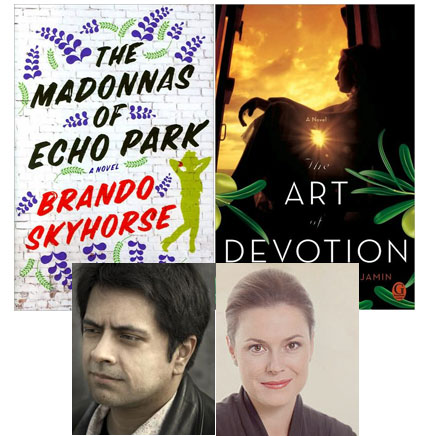

Author2Author: Samantha Bruce-Benjamin & Brando Skyhorse

It’s not true that every editor in the publishing industry has a book in them, but it does happen, and this summer we happen to have two fine examples at hand, Brando Skyhorse‘s The Madonnas of Echo Park and Samantha Bruce-Benjamin‘s The Art of Devotion. I invited the two to ask each other about their experiences as they became published authors—they had plenty to say on the subject, so let’s get right to it…

Brando Skyhorse: Being an editor was an invaluable education in making me a better writer. Do you remember a specific instance where a particular edit offered key ideas in how to approach your own writing?

Samantha Bruce-Benjamin: There was an occasion where I found myself having to do what all editors must at one point in their careers: rewrite someone’s novel for them. Initially, I was thrilled to be asked. Then I read it.

If this particular author used the word “cried” once, then it was used 20,000,000 times—every single page of a 560-page manuscript. Also, everyone “turned,” sometimes “crying” and “turning” all at the same time:

“Give me the techno-diffuser zapper,” the bad guy cried, turning.

“No,” Agent X – the good guy – cried, turning back.

“I mean it. Give it to me now,” he cried louder.

“Will not,” Agent X turned, crying louder than him….…You get the picture. I also imagine that you may suspect I am joking. I am not.

Perhaps my high literary ideals blinded me to the genius of the prose, making me perceive it only as total and utter drivel. I still found myself rewriting every line.

Thirty pages a day. I’ll repeat that: Thirty pages a day, working from editorial sunup to sundown, each and every day for weeks. Then, idiot that I was, I gave the line-edit back to the author, with clear and specific instructions to approve or disapprove the edit by marking clearly in the margins with a green pencil (provided, I might add). The author chose to ignore this somewhat crucial instruction and returned the manuscript, having incorporated the suggestions into a word document—or not having incorporated the suggestions into a word document, as I realized to my endless horror. So I had to do the same thing all over again.

I could be pithy and say that what I learned from this experience was to always have a better writer than myself rewrite my books for me, but the experience did prove invaluable. I genuinely believe that some writers will only create under pressure—I’m certainly one of them. If I had never been forced to rewrite this book, I would never have thought myself capable of writing my own. More than that, I learned, by having my feet held to the editorial fire, the attention to detail required in crafting a plot; the importance of line-editing (in fact, how to line-edit); keeping an eye out for repetition; finding ways to refocus a burnt-out editorial eye after reading a manuscript 100 times throughout the editing period; how crucial it is to turn around something within a timeframe, so that the process doesn’t drag out longer than necessary; finally, I learned when to stop editing and pass the manuscript to production.

This was, by far, the most important lesson. No book will ever be perfect. No edit will ever 100% please an editor or an author. If someone else came along and read the book once it was “edited,” then they’d probably change elements according to their own specifications. Editing could go on forever, if allowed to. So learning when to stop, in tandem with everything else I took from the experience, was my greatest lesson with The Art of Devotion.

So, Mr. Skyhorse, as an editor, how willingly have you submitted to the editorial process?

Brando Skyhorse: Being receptive to edits was easy for two reasons. One, I’m always eager for feedback on my writing. As long as it’s constructive, I’ll take advice or suggestions from anyone. It’s been my experience as an editor that the harder a writer clung to their prose, the more work that prose needed. Two, I’ve known my editor, Amber Qureshi, socially for several years. She knew I was a writer and I knew she was an editor but we never discussed my work because we respected each other as professionals. That mutual respect made taking her edits (and I believe I took 90% of them) a simple decision but even as we worked together I was awestruck by how sensitive and astute a reader she was. Her line edit of Madonnas was perhaps one of the most thorough critiques I’ve ever gotten of my written work. When you see an editor invest dozens of hours into making each sentence better and every character’s motivation clearer, you’d be a fool to discount that input.

You have this luscious backstory for your book in that you summered on a Mediterranean island every year until you were twenty-one. Yet I read in an interview that the desire to write didn’t strike you until you’d been working in the publishing industry for several years. You mean to say that in all those Mediterranean summers where you must have spent endless days gazing out onto that bright blue sea you never set pen to paper? Say it ain’t so!

Samantha Bruce-Benjamin: It is indeed so. The most pivotal, indeed transformative, reading experiences of my life occurred on that island; I was not conscious, when I was creating the novel, of how strongly the literary influences of that period had informed my writing, but it’s all there now that I look: Every book I ever read during the summers of my teenage years, every book I loved deeply, for I was incredibly fortunate to have at my disposal the greatest (in my opinion) works of literature of all time. I have loved reading subsequently, but nothing approached the sheer bliss of discovery against that exquisite backdrop.

I’ll never forget finishing Death in Venice and looking out over the balcony to the sea beyond and the bright, blithe beauty of that particular day and knowing how lucky I was to be there and that nothing would ever come close to replicating that reading experience. There was Tender is the Night, The House of the Spirits, Madame Bovary, Les Liaisons Dangereuses, The Desert of Love… As soon as I start to consider any of these novels, I can find a strain, almost a link, to a certain part of my book and find that author’s influence. It’s like a treasure hunt. It’s a wonderful debt to owe.

Considering your background in the non-fiction editorial field, were you able to bring the same level of editorial precision and objectivity to your creative writing, in terms of honing and shaping the text? Can you editorially critique yourself, without falling prey to authorial insecurity or preciousness?

Brando Skyhorse: Excellent question. As a non-fiction editor, I found it easy to say “move this anecdote here” or “give me more info/details here,” but as I’d only edited one novel for publication in my career, the fiction “voice” I wrote carried a lot more authorial weight. If I write that a character did this thing here…well, it’s fiction, right? Who am I to say that one of my characters should do something else? I could focus on tightening the prose, but even that was a game of diminishing returns because no matter how sharp your eye is, at some point in the process you will need another set of eyes to double check your work. There’s no way you can catch everything yourself. The key for me was to rely on a close circle of friends (one of whom has been reading my stuff for over ten years) who read initial drafts and numerous revisions. Having readers evaluate revisions was crucial in determining when I was on track and when I began to drift.

It’s mentioned in one of your interviews that writing a book’s promotional materials gave you the confidence to write something for yourself. Many people don’t realize how much writing an editor does to help sell their books and how much of that writing is in essence crafting a “story” in a tight space that will intrigue book buyers. Aside from imbuing you with a confidence to start writing, what other assets did such micro-narrative crafting give you while writing your book? And did such a disciplined education help in the revision process?

Samantha Bruce-Benjamin: I did not think editorially at all during the drafting phase; repetition of words, grammatically incorrect sentences—none of it mattered. My objective was simply to tell the story and to realize it on the page, nothing more. I knew that I would never finish the book if I stopped to think about it, if that makes sense. The experience of having worked as an editor was invaluable during the revision process, not only in terms of what I could bring to the table, but also in terms of accepting the opinions of editors and considering them, even when I strongly disagreed. I actually relished the process and I’m very lucky to have such a wonderful editor in Kara Cesare, who so completely understood this book, and whose edit I instinctively gravitated toward, rather than fighting against.

I understood, from the experiences I had both enjoyed and endured working with authors, that there can be no ego in editing. That’s when I stopped being a writer and became an editor again. The way I did this was by pretending that I hadn’t written the novel, rather that it was someone else’s work. It was the only way I could accomplish the objective of honing and revising the work to render it presentable. I didn’t always succeed; subsequent editors, long before the book was published, asked me to remove certain passages and they’re still in there because I couldn’t bear to delete some of the purple prose (even if I did secretly agree with them…).

Do you, like me, have a new-found empathy for your past and present authors—their anxieties and insecurities—given the fact that you have now walked a mile in their shoes?

Brando Skyhorse: I think my MFA background—where your work is torn to shreds every few weeks—and sending out fiction that collected a pile of rejection letters, helped get me on the right foot with most of my authors. Empathy requires understanding and as someone who tried for close to two decades to get his own work published, I knew what kind of journey an author had to get a book accepted for publication and how many obstacles they needed to overcome. It was then my job—my privilege—to give them every ounce of dedication, skill and ability I had. That’s what every published writer deserves and I hope every writer I worked with felt that’s what they got from me.

5 July 2010 | author2author |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.