Hilary Masters and Chekhov’s Eye for Detail

This week’s tribute to SMU Press and its dedication to the art of the short story continues with an essay from Hilary Masters, the author of How the Indians Buried Their Dead. He’s chosen to write about Anton Chekhov, an apt choice considering that one of the stories in this collection is called “Chekhov’s Gun” (which, as it happens, manages to self-consciously invoke the principle and still surprise you with its ending, unless I suppose some blogger comes along and gushes to you about it). But that’s not even the story that’s most relevant here—and there’s plenty more brilliantly poised works in this collection, where you’ll read about futile efforts to revisit a childhood home, a trio of friends grappling with the memory of a departed fourth (along with the limits of that memory), and a perfect example of why one should just about never spontaneously decide to phone one’s exes after years of silence.

Chekhov’s “Lady with the Pet Dog” is a short story I read at least once a year and never tire of his telling of this doomed couple who are punished because they fall in love.

How he tells his story is instructive for all writers. First, how he deceives both the reader and Gurov, the main character, by details that give a false impression of Anna Sergeyvna. What about that dog?

In some versions the small dog is described as a Pomeranian, and in all it is pictured as a decorative but useless animal and so we assume the owner is the same. What impression would Anna give if the dog had been a pit bull or a great Dane?

And that lornette Anna lifts to her eyes is a pretentious article, not really useful for reading, and where does she lose it? In the crush on that sultry day when they meet the boat on the landing just before she “loses” her virtue in Gurov’s arms. Later when he tracks her to her town—where the furnishings of the best hotel’s room reveal what kind of backwater it is—she’s found another lornette, the appearance of propriety restored. For a time.

18 May 2010 | selling shorts |

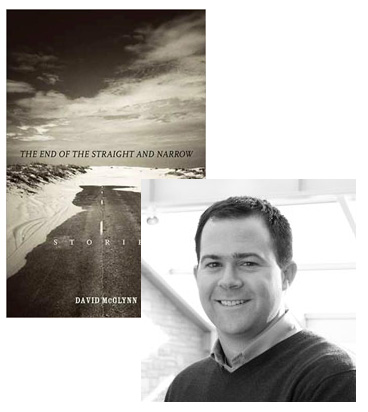

How David McGlynn Found His Home in “Worry”

Like many in the publishing industry, I was stunned two weeks ago when I read about the closing of SMU Press—even though the university has been speaking of this as a “suspension of operations” rather than a full termination, the apparent suddenness of the move, as well as the confusion it has already spawned about both the extensive backlist and the books that were supposed to come out this year, have an air of irrecoverability about them. Folks are doing what they can to persuade SMU to keep the press alive, and I wanted to do what I could to testify to its value—the contributions it has made to the short story genre have been of particularly consistent excellence. With that in mind, I worked on rounding up some of the great short story writers SMU has published and introducing them to you.

Some of them, like David McGlynn, have chosen to write about other authors published by SMU Press. But after you’ve read McGlynn’s take on Scott Blackwood, be sure to read his own collection, The End of the Straight and Narrow. He writes with enormous grace about people dealing with the tensions between their evangelical faith and the pressures of the world—you may not always agree with their actions, but you can’t write them off, either, and you can’t not care about how their stories turn out.

I grew up in Houston, Texas, but moved away the week I turned eighteen, vowing I’d never live there again. The entire state seemed, in my desperation to flee, a haven of rednecks and rockfaces, so utterly boring and suburban that nothing interesting could come from there. Surely no good stories came from there. My parents and grandparents had two books on their shelves I recognized as unmistakably Texan—James Michener’s Texas and Larry McMurtry’s Lonesome Dove, two big tomes my mother used to hold the skinnier books in place. Their names were the only two I knew, and given the size of both books, I was content to leave them quietly on the shelf.

It wasn’t until I was in graduate school and beginning to work on the stories that would eventually become The End of the Straight and Narrow that I found myself once again interested in Texas. My mother lived in Austin, but even still, I didn’t visit more than once a year, and only for a few days at a time. I found myself in a quandary, writing about Texas but feeling cut off from its people and culture. I began casting around for something to read.

Asking for names of Texas writers is sort of like asking for examples of famous rock bands from Georgia. Just as most people can probably name the B-52s, REM, and the Indigo Girls, most readers can rattle off that, in addition to McMurtry and Michener, Donald Barthleme was from Houston, Sandra Cisneros is from San Antonio, and Cormac McCarthy lived in El Paso. I read those writers with enthusiasm, but also with detachment; in each of them, I saw a Texas I recognized but didn’t belong to. Both McMurtry and McCarthy tended toward a Texas without the seemingly endless sprawl of billboards and big box stores and car dealerships, the Texas I knew and remembered. I needed a wider net.

17 May 2010 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.