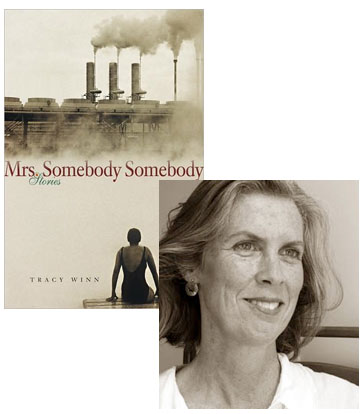

Tracy Winn: Cold Snap Endures

The title story in Tracy Winn‘s Mrs. Somebody Somebody is one of the most effective short stories I’ve read in the last year,a recollection of an ambiguous friendship between two women working in a factory in post-WWII Lowell where the prospect of unionization slowly builds momentum, headed towards a ruthless and inevitable climax before circling back to its original delicate ambiguities. The following stories continue to draw upon the Lowell setting, subtly forming connections to each other but never becoming a “novel in stories,” as they say these days. Random House is publishing the collection in trade paperback this summer, but I wanted to call your attention to the original hardcover release as an example of the excellence SMU Press brings to curating the modern American short story—but may not be able to continue bringing, as the university has somehow decided the press is a non-essential function and is preparing to shut it down (ostensibly not permanently, but one can imagine how difficult it will be to persuade them to flip that switch back if it goes).

Tracy pays tribute to another SMU Press author, Cynthia Morrison Phoel, who will also be putting in an appearance on Beatrice, and after reading this tribute, I can’t wait to see Phoel’s stories. I suspect you might feel the same way.

Cynthia Morrison Phoel has the heart of Charles Baxter, the polish of Alistair MacLeod, the timing of Lorrie Moore, Stuart Dybek’s eye for design, and a subtlety of style that is purely her own. She did her service in the Peace Corps in Bulgaria and Cold Snap is a collection of stories about the people of a fictional Bulgarian town called Old Mountain.

While the lives of her characters, with their Bulgarian particularities, quickly pulled me in, I found myself falling to the much deeper concern of what it means to be human anywhere. In fact, I went down like a candlepin the first time I read one of these stories, “I Guess That Counts For Something,” in a workshop. Seconds into it, I forgot that there was a writer conveying the character’s experience. Phoel presents the power of Neddy’s passion and her struggle without ever calling attention to herself. I’ve looked closely at her craft and it is like magic. Unlike the Wizard of Oz, Phoel stays hidden behind the curtain.

Sometimes, I can’t even find the curtain. I believe that results from the inevitability of her prose and the naturally solid framework that underlies it. Listen to her here, in “I Guess That Counts For Something,” where Neddy is paralyzed by the emptiness of her life:

“By the fourth day of the heat wave, Neddy has come to see it as more of a slow roasting. It is still early, and already sweat bastes her brow, traces her spine, and blanches her breasts and buttocks. The two black dresses she had made when Lubo died are not intended for this weather: constructed of sturdy polyester, they are designed more for endurance than comfort.”

Hear the music in “bastes her brow, traces her spine, and blanches her breasts and buttocks?” Very precise wording is one of the many strengths of Phoel’s art, but I would argue that it is Neddy’s music we hear, not Phoel’s. Neddy’s life, as signaled by her dresses, is “designed more for endurance than comfort.”

Neddy’s progress in “I Guess That Counts For Something” is subtly charted. The incremental shifts, as the character moves through her grief, are grounded in the very solid shapes of a boy’s summer visit, the knitting of a sweater, and a heat wave. The resulting story creates an almost unbearable tension in the reader. Neddy’s predicament is unmediated except by a structure so organic as to be unnoticeable.

Neddy barely moves in the course of the story. Her husband Ludo has been dead for three months and she “does not budge from her seat in the shed… [She] can spend hours like this without so much as a blink or quiver, only shifting on her haunches every now and then to ease a bit of stiffness.”

This character is unforgettably alive in her depression because Phoel, freed by the strength of the story’s structure, delivers Neddy’s situation straight from her heart—a heart so closely aligned in sympathy and understanding for Neddy that the writer disappears.

“And still [the heat wave’s] oppressiveness has caught Neddy off guard. As her breathing takes on a silent pant, she feels duped, not so much by the extraordinary heat, as by the surprise of it all. The last three months have taught her a thing or two about surprise—namely, that expecting, even knowing something is going to happen can’t spare you the blow. That even if you can see a train coming down the track, sometimes all you can do is stand there and let it hit you.”

I could see this story coming right at me, and yet it hit me just that hard. Like many of the characters in Cold Snap, Neddy finds a measure of victory in circumstances that are much richer in limitation than they are in opportunity.

These stories, like the characters that people them, are built to last. Let us hope that the Press making Phoel’s exquisite work available will be allowed to endure along with the stories of the people of Old Mountain.

19 May 2010 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.