How David McGlynn Found His Home in “Worry”

Like many in the publishing industry, I was stunned two weeks ago when I read about the closing of SMU Press—even though the university has been speaking of this as a “suspension of operations” rather than a full termination, the apparent suddenness of the move, as well as the confusion it has already spawned about both the extensive backlist and the books that were supposed to come out this year, have an air of irrecoverability about them. Folks are doing what they can to persuade SMU to keep the press alive, and I wanted to do what I could to testify to its value—the contributions it has made to the short story genre have been of particularly consistent excellence. With that in mind, I worked on rounding up some of the great short story writers SMU has published and introducing them to you.

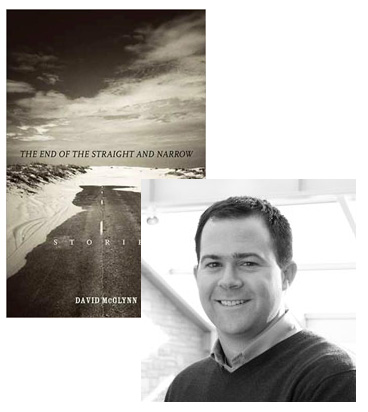

Some of them, like David McGlynn, have chosen to write about other authors published by SMU Press. But after you’ve read McGlynn’s take on Scott Blackwood, be sure to read his own collection, The End of the Straight and Narrow. He writes with enormous grace about people dealing with the tensions between their evangelical faith and the pressures of the world—you may not always agree with their actions, but you can’t write them off, either, and you can’t not care about how their stories turn out.

I grew up in Houston, Texas, but moved away the week I turned eighteen, vowing I’d never live there again. The entire state seemed, in my desperation to flee, a haven of rednecks and rockfaces, so utterly boring and suburban that nothing interesting could come from there. Surely no good stories came from there. My parents and grandparents had two books on their shelves I recognized as unmistakably Texan—James Michener’s Texas and Larry McMurtry’s Lonesome Dove, two big tomes my mother used to hold the skinnier books in place. Their names were the only two I knew, and given the size of both books, I was content to leave them quietly on the shelf.

It wasn’t until I was in graduate school and beginning to work on the stories that would eventually become The End of the Straight and Narrow that I found myself once again interested in Texas. My mother lived in Austin, but even still, I didn’t visit more than once a year, and only for a few days at a time. I found myself in a quandary, writing about Texas but feeling cut off from its people and culture. I began casting around for something to read.

Asking for names of Texas writers is sort of like asking for examples of famous rock bands from Georgia. Just as most people can probably name the B-52s, REM, and the Indigo Girls, most readers can rattle off that, in addition to McMurtry and Michener, Donald Barthleme was from Houston, Sandra Cisneros is from San Antonio, and Cormac McCarthy lived in El Paso. I read those writers with enthusiasm, but also with detachment; in each of them, I saw a Texas I recognized but didn’t belong to. Both McMurtry and McCarthy tended toward a Texas without the seemingly endless sprawl of billboards and big box stores and car dealerships, the Texas I knew and remembered. I needed a wider net.

Soon, to my good fortune, I came across the fiction line at Southern Methodist University Press. Not all of the books were set in Texas—in fact, a good many of them were not—but a few were. The first one I read was In the Shadow of Our House, a collection of stories by Scott Blackwood, and for the first time I saw a Texas that looked and smelled like home. The story I love most is “Worry,” told by a troubled kid named Andrew who hits his brother Michael in the eye with a baseball after catching his father in an adulterous affair. The staccato prose seems to capture Andrew’s fractious thoughts:

My dad one time split open a drunk’s head in the Taco Bell parking lot. It was late. We were coming home from a movie. A Suburban swerved into our lane and almost hit us. “Sonofabitch could’ve flipped us over the median,” Dad said, the veins on his neck standing out. The Suburban went on swerving ahead of us. Mom said let him go, Darnell, he’s drunk. But Dad went after him. He wheeled our car into the Taco Bell parking lot right behind the Suburban and got out…. The wind rolled styrofoam cups around the parking lot. In the Taco Bell, some skinny-ass kid, a little older than me, windexed the glass. The drunk scissor-legged it toward the building. When Dad met him at the door, I remember thinking Dad was maybe going to talk to him because he put a hand to the drunk’s shoulder, soft, like a tap. The drunk’s hands were jammed in his pockets. He turned around, said something to Dad, then grabbed for the door handle. Dad swung and hit the man in the belly and his legs crumpled, like Michael’s when the baseball hit him.

Words fail, as a character from another story says. Language is inadequate, and the legacy of violence is more violence, more discord. More personally, the story brought to mind the lost shards of memory from my own life that I would soon use to get my own book off the ground. I recalled the time when two men robbed a bank around the corner from my house, and set a car on fire in the parking lot of our local grocery store to cause a distraction. My mother and I were in the store when the car caught fire, and when we got home, our neighbor told us the bandits had pointed their gun at her when she screamed for them to slow down. I remembered the boys around the corner from my house who jumped off the roof of a two-story house after doing a few bumps of acid. The salesman who swindled my parents out of the money they were going to use to install a swimming pool. My sister’s godfather, arrested for selling cocaine. And yet Blackwoods’ people find their way to solace, even moments of grace. I never felt drowned in despair, though I did swim in it a while, and coming back to dry land, I knew not to take happiness for granted.

The New York Times called the stories “so honest… they capture the dapple of emotions and perceptions that cross the mind like sunlight and shadow on a river.” I used the same words when I recommended the collection to friends. I stammered out something similar, that far less coherent, when I approached the author at a conference, told him I loved his work and wanted to be his friend. The consummate Texan, Scott obliged.

17 May 2010 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.