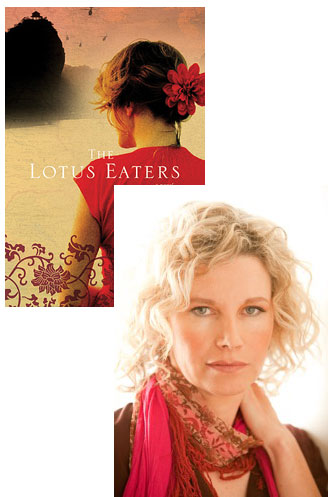

Tatjana Soli and Fiction That Leaps into Danger

The Lotus Eaters opens in the chaotic moments before the fall of Saigon, then jumps back in time, showing how its three main characters came together as combat photographers in the early years of America’s involvement in the Vietnam War. I’m still in the first half of Tatjana Soli‘s story, but I’m captivated with the interlocking relationships, and with how she manages to capture the intricacies of working in a visual art form through verbal language. Her emotional commitment to this story comes through on every page, and I wanted to hear more from her about what drove her to tell this story, about these people…

One of the more fascinating things that happen to you as an author with a book out is the experience of bookstore events where readers come up to you to discuss your characters. This is both immensely gratifying and surreal. For years, this was a private relationship, and now suddenly it’s like you and your characters are on a reality show. Lately, going around to readings and talking about my novel, I’ve had readers want to discuss my main character, Helen: “She’s reckless.” I’ve also heard: “She makes me angry.” And whispered: “Who in their right mind would do this?” I understand. I’m sympathetic. I shuffle my feet. After all, I’ve been living with her for years.

Ten years ago, I came across a picture of a woman photojournalist in Vietnam who wore pearl earrings. Women in that war? And why the earrings? That mystery led me to discover a whole tribe of Amazon-like women that I had never been aware of before: from Dickey Chapelle and Catherine Leroy in Vietnam to contemporary photojournalists such as Stephanie Sinclair and Margaret Moth. There were other female journalists, writers, but photographers fascinated me for one simple reason: they can’t fake it. As in the famous Robert Capa quote: “If your pictures aren’t good enough you aren’t close enough.” Maybe the same can be said for writers. We are always trying to create fiction in which the reader can get as close as possible to the characters, but sometimes that takes him or her to an uncomfortable place. How to understand the seeming recklessness of a character, her hunting out of danger?

The great journalists do what they do because they have a deep desire to be part of history, to record its unfolding. As Stephanie Sinclair put it: “People in general just want to be part of documenting history and witnessing it and being a voice for the people.” As in any profession, there’s also the clear and obvious lure of ambition, of having one’s work seen around the world, of winning accolades, of mattering. Another element that we’ve been made aware of in such movies as The Hurt Locker is the adrenaline rush of war, of danger. But there is one more reason that was harder to describe without being unseemly, and I had not really tried to talk about it until I read an earlier Beatrice contributor, Paul Harris, mention it. His secret—that covering war is fun—is what I had been avoiding. Being a war correspondent is many things, but fun? But it was undeniably there, again and again.

In Perry Deane Young’s Two of the Missing, his account of his friends Dana Stone and Sean Flynn going missing in Communist-held territory in Cambodia in 1970, when his colleague tells him about their disappearance and says not to worry, Young answers: “Don’t worry? I wish to hell I were with them!” Michael Herr, author of Dispatches, writes: “We had Vietnam instead of happy childhoods.” Tim O’Brien speaks of the kind of truth that can better be uncovered by story-truth rather than happening–truth. He is getting at emotional truth, and the idea of war being on some level fun is one of those truths that go against logic, that needs to be conveyed in story truth. What these journalists are talking about is not loving violence but loving the intensity of war, an intensity out of which an extraordinary camaraderie forms.

Saigon was about war and suffering, but it also had parties and dinners, it had both sex and love, in varying proportions. Observers might think it disrespectful to include the light in undeniable darkness, but as human beings, it is the truth by which we survive. People who put their lives on the line day after day want to enjoy the good parts of life too. The striking Margaret Moth was shot in the face and disfigured in Sarajevo. As soon as she recovered, she demanded to go back to war coverage, her passion. As she put it: “You could be a billionaire, and you couldn’t pay to do the things we’ve done… the important thing is to know you’ve lived your life to the fullest.”

15 May 2010 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.