Christopher Farnsworth’s Procession of the Damned

When I read an advance copy of Blood Oath last Christmas, I described it on Twitter as being like “Robert Ludlum’s Hellboy,” which I’m here to tell you is a damned awesome thing to be like. (In a nutshell: America has a superspy, and he’s a vampire… and he’s stuck with a partner.) I especially dug how Christopher Farnsworth loaded up on backstory, dropping hints about how America’s vampire defender had shaped the nation’s history behind the scenes…and when I found out where he got the inspiration for this story, I realized that we had a mutual fondness for one of the truly great eccentrics of American literature, an author who created for himself one of the most distinctive voices of the 20th century.

“A procession of the damned. By the damned, I mean the excluded… We shall have a procession of data that science has excluded.â€

I was 11 years old when I read those words for the first time. They were the opening lines of The Book of the Damned, quoted by Daniel Cohen. I was already a regular visitor to the 130 section of my public library. But that was when I first learned about Charles Hoy Fort.

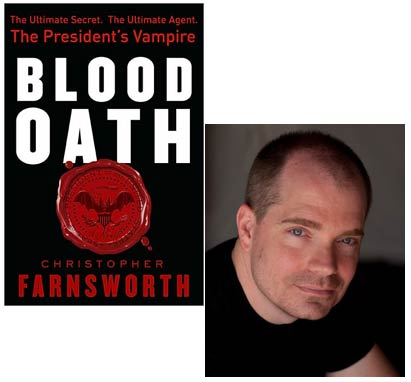

No joke: he changed my life. And he continues to change it. Blood Oath, my first novel, is going to be published on May 18. It’s about a vampire who works for the President of the United States. It’s a combination of the spy thriller and the horror story, and includes many of the anomalous chunks that don’t fit in the regular American history books.

It wouldn’t exist without Fort.

Fort dug through thousands of newspaper clippings, looking for the odd bits of news that couldn’t be explained. Showers of fish and frogs raining from the sky. People and things vanishing into thin air before sober witnesses. Poltergeists. Wolf children. Perpetual motion machines.

For a kid like me — bookish, weird, and often excluded himself — these were trips into a world richer than the gray-toned reality where I lived. There’s a whole generation that doesn’t know anything but the world with the Internet. It might be hard to imagine, but once upon a time — when I went to school in twenty feet of snow uphill both ways — it was hard to be strange. The paranormal hadn’t been mainstreamed yet. Long before “The X-Files,†“MonsterQuest†and grainy YouTube videos of UFOs, Fort was a nearly infinite resource for anyone looking for evidence that the world was more than it seemed.

Fort was an outsider: painfully shy, practically disowned by his father for his dream of becoming a writer, and contrarian to the point of refusing to join the society founded in his honor. Despite that, he was popular. His books went through several printings, and he was part of the New York literary set that included his friend and champion, Theodore Dreiser.

His books today seem so far ahead of their time as to have looped back around to the past. He coined the term “teleportation.” He suggests concepts similar to chaos theory and quantum entanglement. He argues for the uncertainty of all things, and the inability of the observer to separate himself from the observed. He’s suspicious of all authority, and dismisses experts as delusional.

I’m not a Fortean anymore. Once I honestly subscribed to the Fortean ethos, best expressed by Loren Coleman: “I believe in nothing; I believe in the possibility of everything.†I still find that a lovely sentiment, but I don’t buy it. My time as a reporter left me too drenched in cynicism.

But I never gave up on Fort, or enjoying all the work done by his followers.

The kernel of the idea that became Blood Oath started with one of those clippings unearthed by Fort and published in his final book, Wild Talents. I came across it in Robert Schneck’s book of Fortean stories, The President’s Vampire. It got me wondering: why would a president pardon a vampire?

The novel began right there.

I’m not sure what Fort would make of the mood in America right now. In many ways, it seems like the weirdness in his books has broken free and overpowered any rational narrative. Case in point: a legislative committee in Georgia recently heard evidence about the sinister government agencies forcibly implanting microchips in people. You don’t have to dig in hidden stacks to find that information— it’s a headline all over the country. We all just shrug and move on.

Even the strangest things can become everyday. If we could see Bigfoot in a zoo, eventually it would be just a regular part of the sixth grade field trip.

That’s probably why Fort resisted giving a definite answer for any of the odd stories he collected. We tend to believe in stories, not facts. We’re looking for myths, not reasons.

Above all, Fort reminds us there are always pieces of the world that defy explanation. There will always be something anomalous, something baffling, something spooky. No matter how much we learn, we’ll always have another mystery to chase.

Personally, I wouldn’t want it any other way.

28 April 2010 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.