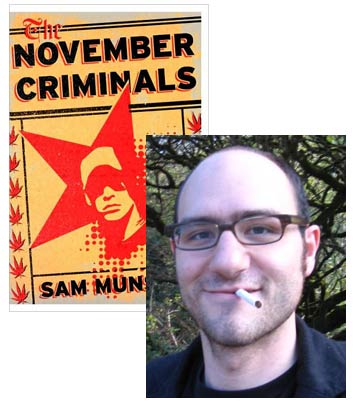

Sam Munson Looks Back at His Second-Rate Home Town

Before the hate mail starts pouring in from our nation’s capital, this is probably as good a time as any to remind readers that the opinions expressed by Beatriceguest authors don’t necessarily reflect those of the site’s editor—that said, I didn’t grow up in Washington, D.C., so Sam Munson is in a greater position of authority to speak about his hometown than I am. New Yorkers can hear him read from his debut novel, The November Criminals, tonight at Brooklyn’s Melville House; he’ll be at Washington’s Politics & Prose in mid-June. (Oh, and I meant to note the cleverness of releasing a novel about a teenage pot dealer with an official pub date of April 20… if I hadn’t had a good reason to post something else yesterday, I would’ve played along with the gag!)

One of the two main reasons for the existence of The November Criminals: the fact that Washington, D.C., is a second-rate city. I mean this both pejoratively and as the most direct way of evoking its true character. You could argue that this was part of the intent of its founding—let’s build a city, the founders said, over this swamp, in political no-man’s land, to help defuse potential factional squabbles about state ownership of the Republic’s capital. Reasonable enough, then, that the resulting city would not be Paris or Rome (you can’t build Paris or Rome simply by willing it) but a place the likes of which I have yet to encounter outside of America.

The city with the most similar atmosphere—social stasis, an active and completely philistine attitude towards the arts, relative affluence, and a deep, uncomfortable silence about the past permeating everything—is Munich, the federal capital of Bavaria. D.C. is pretty, with copious greenery and flowers, a lot of sky, dainty Georgian and neoclassical architecture, mild weather (except for the summers, when its origins as a swamp become feverishly clear) and two rivers that—even in the worst days of their pollution—still meandered impressively among the buildings, bridges, and parkways of downtown.

D.C. is conspicuously not, however, beautiful.

It lacks any major civic parks or landmark architecture, aside from a few monuments. It sits near an estuary, not an ocean. It lacks a signature food (half-smokes are made by butchers in Baltimore, all you Ben’s Chili Bowl fakers and Johnny-Come-Latelies); the closest it comes is a condiment, mumbo or mambo sauce (spelling varies). The subway closes early. Cabs, until about eighteen months ago, charged you according to an indecipherable zone system; meters arrived in 2008. Tri-Staters don’t invade D.C. on the weekends, but murder-eyed rednecks (and even worse, Bethesdans) do. (D.C., by the way, has a huge population of indigenous, city-born hicks. An impossibility, you say. Sadly, no—sometimes you walk around and it’s like being Western Pennsylvania: paunches, tow-heads, flat twangs, bad teeth.)

It’s the seat of government, yes, but ultimately this makes it nothing more than a company town, and a general air of lackeyism pervades all professional life there.

I could go on: I could mention the horrific racial divide the city suffered from when I was growing up, and the blithe moral moronism of the empty-headed progressive zombies who taught me (with a few exceptions) English and history, who staff think tanks and the Hill. But then we would be here all day. If that’s really your thing, read The November Criminals, which is as much about race as it is this quality of second-rate-ness I’ve been trying to nail down. The race problems might even be subsumed within the larger problem of second-rate-ness. Although that’s something for the sociologists to figure out, I suppose. And let me add a caveat here: I have not lived in D.C., really lived there, for years, so don’t get all up-in-arms about my derision. Or you can, but just remember I’m talking about the past.

Recent visits have suggested that D.C. is now home to an array of what I can only describe as failed Brooklynites (!), of the hipster, hipster-in-denial, washed-up-hipster, and young parent varieties, with a concomitant array of aspirantly-cool bars. And this phenomenon can fuel—well, something. After all, what’s worse than seeing something inherently second-rate try to disguise its nature? It’s disgusting; it’s sick and it’s sad, etc. I don’t intend this as a defense of the second-rate. I don’t know how well it explains or clarifies the novel. How can the second-rate serve to inspire you to—well, do anything?

The November Criminals‘ narrator, Addison Schacht, is certainly aware of our shared hometown’s defects; it fuels his purism, or what an early reviewer described as his fanaticism. And maybe that’s it: maybe fanaticism doesn’t arise from some powerful positive philosophy bur from an allergy to the mediocre—which is to say, in many cases, reality itself. This seems like a much more plausible account, given the constitution of the human personality. At least as I understand it. But I, as I’ve often been told, am cynical and negative. So what do I know?

21 April 2010 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.