Fred Moten, “Njeeri Wa Thiong’o”

in the world to scream against

the invading encloser, always crossing

past return, an advent, we were herebefore the sad absences. we are philosophical

contraband. our braid flew off the

circle from inside like a pathogenic

bass line. the point of the contraband

was the other ones, like the ProphetessAmanda Irving praying for the

lost ones, in protest, committing

thy body to the bass line, inturning reading everything.

it gives me pleasure to ask that you

pray for me before we raise the broken cityto make another world.

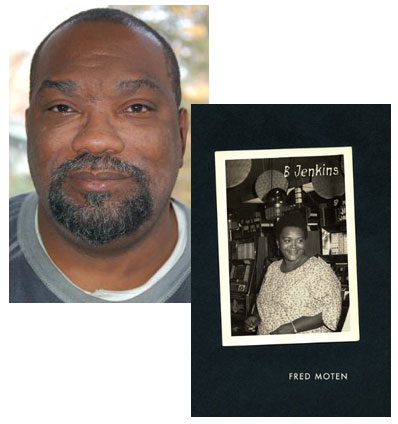

B Jenkins, Fred Moten’s fourth collection of poems, is named after his mother, who is the subject of two poems. He read several poems from the collection at a PennSound reading n 2008.

Moten’s poems explore some of the same themes as the cultural criticism of In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition; in an interview in the back of B Jenkins, he explains: “I want my criticism to sound like somethng, to be musical and actually to figure in some iconic way the art and life that it’s talking about. At the same time, I also wan tmy poetry to engage in inquiry and to intervene, especially, in a set of philosophical and aesthetic questions that are, I think, of profound political importance.”

(Njeeri Wa Thiong’o, also often recognized as Njeeri Wa Ngugi, is the wife of Kenyan novelist Ngugi Wa Thiong’o; the couple were the victims of a brutal assault in August 2003, shortly after they returned to Kenya after decades of political exile.)

14 February 2010 | poetry |

Catie Rosemurgy, “Variorum”

At least most of the violence has been off the page.

Most of the violence, at least, has been kept off the page.

Most of the violence takes place off the page, as is always the case.

None of the violence is ever on the page.

Violence is never on the page.

The violence thus far has primarily taken place off the page.

The violence thus far has been implied.

For the most part, the violence is not on the page.

For the most part, this page is not violent.

The page really can’t be violent. At least.

The page, for the most part, takes place off the page!

At least the violence. At least for the most part.

As usual, for the most part, as is always the case.

As usual, most violence happens off the page.

As usual, the page. Mostly the violence.

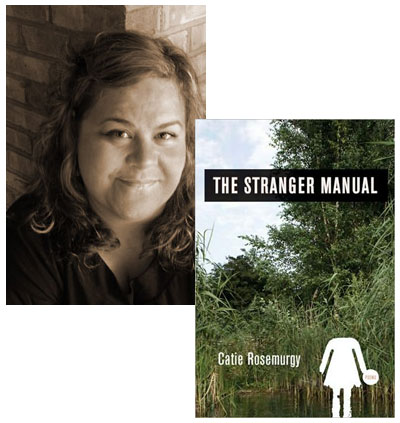

Although this poem does not, many of the poems in The Stranger Manual concern “a sort of alter ego” (according to the jacket copy) named Miss Peach; see, for example, “The Monkey Whose Job It Used to Be to Sit on Miss Peach’s Shoulder Takes Up Olde Timey Music” (originally published in Blackbird), Miss Peach: The Novel” (Boston Review), or Miss Peach: Female Impersonator” (spotlighted by the National Endowment for the Arts to commemorate a grant given to the poet). You can read three more poems at Diagram, at least one of which refers to Miss Peach, and Kenyon Review published “New York, New York, New York, New York, New York.”

In an interview with Corduroy Books, Rosemurgy describes Miss Peach as “maybe more a concretization of a series of questions than a character… She’s a vehicle. She embodied ideas I didn’t know I was wrestling with.” She elaborated in an interview with Bomb: “I wanted to play with the notion of the fictional character sent lost and roaming outside of its usual territory (the novel or story). Miss Peach began as a satire, really, of female character types—the post-feminist super shopper, the doomed heroine of the romantic novel, the cruelly thin sorority girl. But as she morphed more and more and became increasingly pliable, ridiculous, and monstrous, I developed deeply unironic feelings for her and wanted to follow her storyline, though what happens to her only comes through in flashes.”

10 February 2010 | poetry |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.