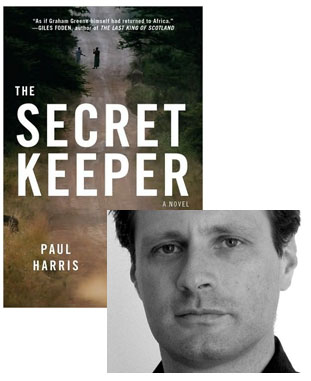

Paul Harris & The War Correspondent’s Secret

I met Paul Harris, the American correspondent for The Observer, last year at a party celebrating the release of his debut novel, The Secret Keeper; I’d gotten to the bar a bit ahead of the rest of the crowd, so by the time he walked in, I was already immersed in the opening chapters. Now that the novel’s out in paperback, Paul wanted to share some thoughts upon how it draws upon his professional—and emotional—experiences before he came to the States…

The title of a talk I went to recently at Columbia University was slightly titillating. It was called “The Secret Life of War Reporters” and was inspired by Donald Marguiles’ current hit play Time Stands Still. The panel included two very distinguished war correspondents, one photographer and one writer. Both of them—like myself—no longer cover conflicts, but they talked openly and frankly about the strange world of war reporting that had defined their careers and much of their lives.

They covered the usual ground familiar to most people from countless films and books about war reporting. There was the agonising over the ethical dilemmas of essentially being a tourist in someone else’s tragedy. There was a discussion of the high physical and mental price that brave journalists pay in order to bring light to otherwise awful events. There was talk of courage and doing good in the world. It was all true and admirable. But a “secret”? Not really.

Yet there is a dirty secret in the life of many war reporters. It was certainly present in my own experiences as a reporter in Africa and while embedded with the British army in Iraq during the 2003 invasion. It is also something I explore in The Secret Keeper, which was inspired by my experiences covering the end of the civil war in the West African country of Sierra Leone. That secret is that in many ways war reporting is tremendously good fun.

It seems horribly wrong to use “fun” in that context. Witnessing death and massacre is not fun. International tragedies are not fun. But, horribly, reporting on them can be. While journalists are motivated by higher ideals of truth and justice in reporting on conflict, they are also motivated by the sheer excitement and thrill. When I was in Sierra Leone—as a young man with an apparent need to prove myself (though God knows who to)—I loved getting up each morning and dodging roadblocks around Freetown. It was something that was hard to admit to myself at the time, but looking back seems obvious. I enjoyed the danger. I got a kick out of it. It made for great stories in the bar later in the evening (and every war zone has many such bars, many such stories and many people telling them).

In The Secret Keeper, my journalist protagonist, Danny Kellerman, is lucky to leave a protest in Freetown shortly before a shooting breaks out. A colleague is not so lucky and witnesses awful scenes of people being killed and comes close to being shot herself. Danny, to his amazement, realises he is jealous. It sounds a crazy reaction—it is crazy—but it is an incident from my own life. I had felt precisely that way when I missed out on being present at a mass shooting that had almost seen a colleague die. There were many times when I genuinely wanted to be present while bad things were happening. I remember covering a riot in a South African township. Suddenly shooting broke out and I found myself crouched behind a car, taking cover with a local reporter. We were both pulling out our mobile phones to call our desks as the shots rang out (that had been our first instinct, after ducking). We caught each other’s eye as we held the phones up to our ears and both started laughing. We were, amazingly, having the time of our lives.

The other secret, of course, is that being a war correspondent is very good for your career. It may be traumatizing, it may be hard work in the service of the greater good, but it is also guaranteed to get the admiring attention of most editors. There is an element of self-interest in any war reporter, along with the bravery and sacrifice. None of this is to downplay the good side of war reporters, which far outweighs the bad. I have colleagues whose body of work is utterly humbling and who have done amazing things in the service of the powerless. But the real secret lives of war reporters should not be ignored. In my book, perhaps out of some sense of guilt at my own behaviour and feelings, I try to explore some of that dark side.

21 February 2010 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.