Lauren Kate’s Case for Selective Reading

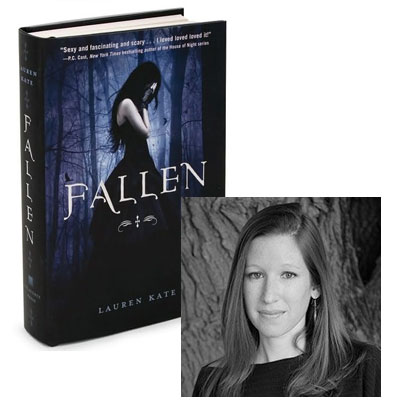

I stayed up until 2 A.M. the other night to read Lauren Kate‘s Fallen in one sitting—well, technically, after reading the first 50 pages on the subway home—compelled by my curiosity about how the drama was going to play out—I’d grasped pretty early on that Daniel, the mysterious boy the novel’s heroine becomes fixated on shortly after her arrival at a harsh new reform school, was at the very least immortal and probably a fallen angel, but I looked forward to finding out just who else in the supporting cast had more to them than met the eye as the story hurtled towards its climax. (Which, fair warning, sets up as much if not more than it resolves.) Today’s essay kicks off a two-week blog tour for Kate; tomorrow, for example, she’ll be visiting Through a Glass, Darkly.

When I was ten months old, my mother made an appointment with our ear doctor because she thought I was deaf. Hearing the story told for the first time to my husband recently, I was impressed by my mom’s verve as she relayed the family lore. Her eyes lit up telling of the placid way I’d stare into space when she tried to reason with me, how often I ignored my name being called.

A half-hour doctor’s visit revealed perfectly sound hearing in both my ears, and left only one explanation: at less than a year old, I was already selectively hearing my mother. (This is when my dad chimes in: “smart kid.”)

When people invoke the term “selective memory” or when my mother refers to my lifelong “selective hearing,” they’re referring to a way of tuning out what, for whatever reason, we don’t want to retain. Those terms get a bad rap, but I’d like to make a case for selective reading—tuning out or tuning up certain moments in a narrative—as a key to reading fiction.

When readers and reviewers talk about the “worlds” within my novels, I often have a hard time taking credit for them. Descriptive passages are some of the most challenging for me to write. Scenes that exist in vivid, specific detail in my mind often have to be teased out of me by my editor and agent. I’d like to say this isn’t laziness, but a desire to leave enough to the imagination of my readers.

One of the things I love most about reading is sharing in the author’s effort to create the world of a story. The books I open again and again always require active participation on my end; they insist that I split the creative load fifty-fifty with the author.

For example, I know that the light across the bay at Daisy’s house is green, but Fitzgerald leave it up to me to image Gatsby’s nightly posture as he stares at it, how dim his own great house is behind him, and the precise angle at which Nick watches him doing this. No one else will ever read The Great Gatsby in just the same way I read it, no one will picture the characters in just the same way I do. To share in the invention of a world is to do something powerful. It allows for an important intimacy between a reader and a book.

I get a lot of questions from parents of teenagers asking whether Fallen, my book about the earthly affairs of fallen angels, is appropriate for their daughter. Yesofcourse, bellows my publisher’s voice inside of me, but the truth is, I have no idea. I don’t know who you are, what your kid is like or wants to be like, whether a love scene might strike you as too illicit and your daughter as too tepid—or vice versa.

The most honest answer I can give invokes selective reading. Being in control of half of the story allows us readers to make a sex scene just as racy or just as comfortable as we want. To make monsters or murderers only as terrifying as we want them to be. This imaginative freedom and control is what makes many of us prefer books to their movie versions. It’s what allows a story—one that might be worlds away from anything we’ll ever experience—not just to speak to us, but to fill in gaps in our own lives. It’s what causes the same reader to have vastly different experiences reading a book at eighteen and again at sixty-eight. And maybe what gives mothers and daughters opposite—yet equally satisfying—reading experiences when they crack open a paranormal teen romance.

Speaking of mothers and daughters, I’ve been listening to my mother more and more. But I supposed in other areas, I haven’t changed so much from the stubborn kid tuning her out: Today, when I crack open a book, I bring my own constantly changing expectations and desires. I read selectively to make bring myself closest to the world inside that book, and to bring the book closest to my world beyond the page.

11 January 2010 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.