Read This: Abe’s Penny

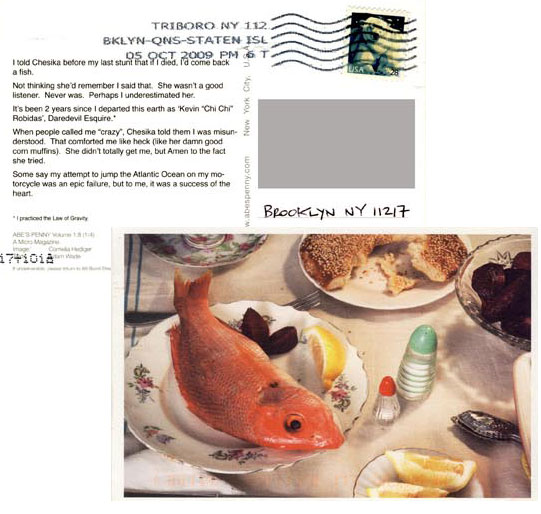

Abe’s Penny is a great concept: a “micro-magazine” that, each month, spreads a photo-illustrated poem out over four postcards, mailed out to subscribers a week apart. Sisters Anna and Tess Knoebel started the publication back in March; the postcard above is the first installment of the eighth issue, which juxtaposes photographs by Cornelia Hediger with a narrative poem (perhaps even a short-short story) by Adam Wade.

A six-month subscription is $48; a full year goes for $82. Seems like a great investment—pair Abe’s Penny up with One Story and it looks like you’d get plenty of reading goodness and no problems keeping up with it.

6 December 2009 | read this |

Peter Sherwood, Breathing in the Language of Miklos Vamos’ Book of Fathers

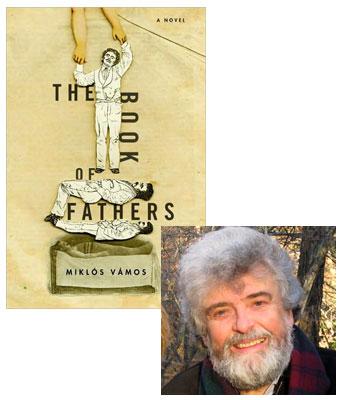

If you saw The New Yorker‘s brief notice this week of Miklós Vámos’s The Book of Fathers, which describes the novel as “a unique and affecting illustration of the vicissitudes of Hungarian history,” perhaps you wanted to learn more. You’re in luck—translator Peter Sherwood was kind enough to send us this short essay about Vámos and Hungarian literature. I’m looking forward to reading it later this month—in the meantime, Prof. Sherwood let me look at a short story by Dezs Kosztolányi he’d translated recently, so I know the Vámos should be excellent reading.

“A novel” it says on the eye-catching cover, but Miklós Vámos’s The Book of Fathers is a highly readable saga spanning the last three centuries of Hungarian history, so perhaps a brief introduction won’t come amiss. Quite unrelated to the languages around it, Hungarian, together with its speakers, has nevertheless been an integral part of Europe for more than 1100 years. This context provides not only the setting for Hungary’s extraordinary history—which vastly overflows its contemporary borders—but also the tension that drives Hungarian culture and my lifelong interest in it.

Though language is nowadays widely accepted as the touchstone of national identity, Hungarians have long been intensely aware of the isolation and distinctiveness of their tongue—both a plus and a minus, often at the same time —and have always particularly prized its embodiment in literature as their highest cultural value. As writers have regrouped over the last two decades and cleansed the language of the mire of Communistspeak, acceptance of the best-known contemporary literary personality Péter Esterházy’s dictum that “it is better for the writer to think in terms of ‘subject’ and ‘predicate’ than ‘people’ and ‘nation'” has increasingly meant that a number of Hungary’s most outstanding writers speak to the whole world, even as they often (paradoxically) try to exorcise the Hungarian past and mine linguistic registers unexploited under even soft Communism. Only a few of their works are available in English translation, and not all of these do justice to the originals; and even those that do, give only a hint of the enormous range and vitality of Hungarian literature in our time.

4 December 2009 | in translation |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.