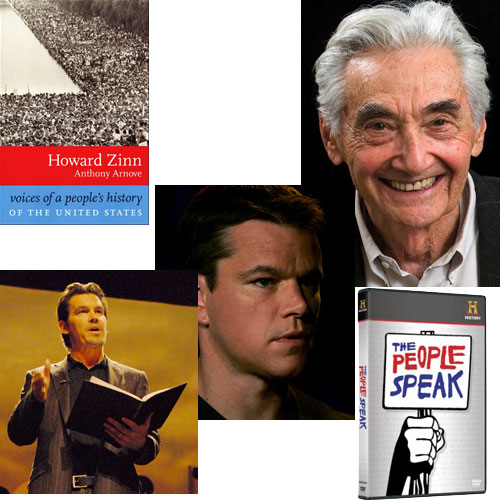

Watch This: The People Speak

One of my favorite experiences during the two years I spent as a copywriter at Amazon was creating an opportunity to interview Howard Zinn—I forget what publishing rationale prompted me to make the call, but since I was already a fan, I was thrilled to speak with him for something like 30 minutes. I remember we talked about the efforts to impeach Bill Clinton, and how it was all classic “bread and circuses,” and we talked a little bit about the boost he’d gotten from Matt Damon’s mention of A People’s History of the United States in Good Will Hunting.

Anyway, shortly after that, I’d heard that Damon and Ben Affleck were trying to do a sweeping mini-series version of A People’s History with, of all studios, Fox; over the years, that project morphed into Damon and Josh Brolin recruiting a group of celebrities to read passages from Zinn’s Voices of a People’s History of the United States, an anthology of primary documents (co-edited by Anthony Arnove) from Eugene Debs, Frederick Douglass, Emma Goldman, and so on. Those readings, along with musical performances by Bruce Springsteen, Alison Moorer, Eddie Vedder, and others, were filmed for The People Speak, which premiered on the History Channel last night and may very well air again in the days ahead; it’s also coming out on DVD fairly soon. (That last link, by the way, includes some video excerpts worth checking out.)

Two of my favorite moments in the film were Brolin reading a passage from Dalton Trumbo’s Johnny Got His Gun, one of the most blunt anti-war novels ever written (which Trumbo would later turn into an equally powerful movie) and Damon reading the famous “I’ll be there” passage from Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath. But there’s a lot else to admire in this documentary—and I believe there will also be a CD version as well, which actually makes a little more sense as these are statements that should be listened to carefully, and separating them out from the (fairly static) visual presentation may make that a bit easier for some.

(photos courtesy of The History Channel)

14 December 2009 | watch this |

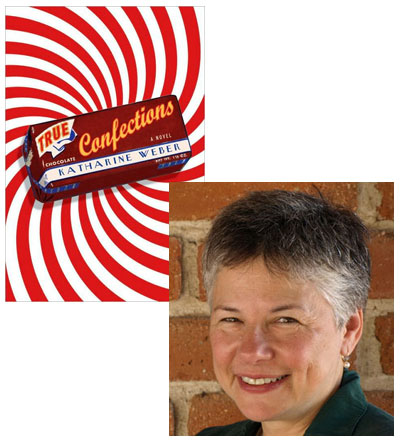

Katharine Weber Is Keeping It Unreal

I just started reading Katharine Weber’s new novel, True Confections, in preparation for her appearance next month (Monday, January 11) as part of the author/blogger discussion series I curate for Greenlight Bookstore, the independent shop that recently opened in Fort Greene. (I’m only introducing the evening’s discussion; Weber will be interviewed by Levi Asher of Literary Kicks.) In the novel, Alice Tatnall Ziplinsky purports to be telling the history of Zip’s Candies, the Ziplinsky family business, but it is immediately (and amusingly) apparent just a few pages into the first chapter that for all Alice’s insistence on the “truth,” there’s an agenda at play. Now, as somebody who grew up seeing the Schrafft’s sign from the highway driving through Boston growing up, I suppose there’s a bit of me that wonders if Zip’s is based on any real family-owned candy business… but Weber would like to remind us that such questions are, for the purposes of fiction writing, rather beside the point.

To write a novel is to engage in an invented reality over an extended period of time. The willing suspension of disbelief that we expect from our readers has to start with the writer’s own willing suspension of disbelief beginning with the first intentions about the novel. Over the months and years of writing, as the novelist willingly and gladly dwells in this alternate realm every moment she spends wrestling with sentences (and for most other waking hours as well, spent away only from the physical task of writing it down), the world of the novel looms larger and larger, becoming more and more specific and vivid.

This conjured reality doesn’t cease to exist when the novel is finished. The opposite is true; full knowledge of these people in this time and place, and all its verities, is deepened through the revision process. Editing and then copy editing offer fresh challenges to the author’s authority to justify the information, stated and implied, of the novel’s internal logic. Whether it is the consequence of the way gravity reverses with every completed rotation around its three suns on the planet Zorth, or the telltale moment that occurs in the middle of a peculiar ritual of birthday party toasts practiced by a family in rural Kentucky during the Civil War, the integrity of the invented reality must be deeply known and experienced by its inventor in order to succeed. Writing a novel is a kind of extended phantom tour of duty in this other place, even as we go about our ordinary lives.

Once the book is out in the world it can be quite disturbing when this reality is resisted and misunderstood by readers. The willing suspension of disbelief is necessary to the fundamental transaction between the reader and the writer—in exchange for a willingness to believe, the reader gets to be entertained by the novel. But the contemporary reader seems these days far less willing or able to transact business with the authors of contemporary novels that are not magical, set in the distant past or future, or filled with vampires.

13 December 2009 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.