Peter Sherwood, Breathing in the Language of Miklos Vamos’ Book of Fathers

If you saw The New Yorker‘s brief notice this week of Miklós Vámos’s The Book of Fathers, which describes the novel as “a unique and affecting illustration of the vicissitudes of Hungarian history,” perhaps you wanted to learn more. You’re in luck—translator Peter Sherwood was kind enough to send us this short essay about Vámos and Hungarian literature. I’m looking forward to reading it later this month—in the meantime, Prof. Sherwood let me look at a short story by Dezs Kosztolányi he’d translated recently, so I know the Vámos should be excellent reading.

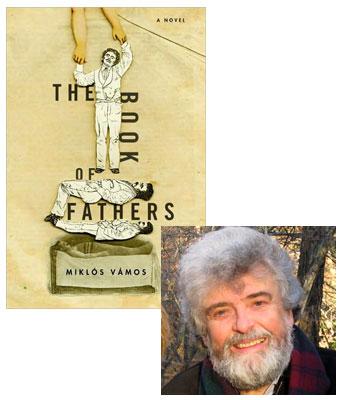

“A novel” it says on the eye-catching cover, but Miklós Vámos’s The Book of Fathers is a highly readable saga spanning the last three centuries of Hungarian history, so perhaps a brief introduction won’t come amiss. Quite unrelated to the languages around it, Hungarian, together with its speakers, has nevertheless been an integral part of Europe for more than 1100 years. This context provides not only the setting for Hungary’s extraordinary history—which vastly overflows its contemporary borders—but also the tension that drives Hungarian culture and my lifelong interest in it.

Though language is nowadays widely accepted as the touchstone of national identity, Hungarians have long been intensely aware of the isolation and distinctiveness of their tongue—both a plus and a minus, often at the same time —and have always particularly prized its embodiment in literature as their highest cultural value. As writers have regrouped over the last two decades and cleansed the language of the mire of Communistspeak, acceptance of the best-known contemporary literary personality Péter Esterházy’s dictum that “it is better for the writer to think in terms of ‘subject’ and ‘predicate’ than ‘people’ and ‘nation'” has increasingly meant that a number of Hungary’s most outstanding writers speak to the whole world, even as they often (paradoxically) try to exorcise the Hungarian past and mine linguistic registers unexploited under even soft Communism. Only a few of their works are available in English translation, and not all of these do justice to the originals; and even those that do, give only a hint of the enormous range and vitality of Hungarian literature in our time.

(I should perhaps make it clear to those who have come across their names that I am not, here, concerned with the interwar stylists Sándor Márai and Antal Szerb, who have in recent years enjoyed a degree of commercial success thanks to very fine English versions. While they have their well-deserved merits and historic place, these two writers in particular are for me now past their sell-by date. There are, of course, many Hungarian classics well deserving of an English translation.)

Probably, especially in the current climate, Western publishers are too cautious, and certainly the number of good translators is too few—a vicious circle. I was therefore very pleased to be given the chance to translate The Book of Fathers, a work with an intriguing premise imaginatively elaborated, which goes some way towards giving a more nuanced picture of what Hungarians are reading these days (the original, published in 2000, sold more than 200,000 copies; the total population of Hungary is ten million.) I was also attracted by its take on the complex evolution over time of the very important Jewish element in Hungarian society: this book says more than many scholarly studies of Jewish “identity” and with greater subtlety than (say) István Szabó’s glossy film Sunshine, which it in some respects recalls.

Finally, but by no means least, I was excited by the challenge of re-creating Vámos’s language, which tries to match that of each of his twelve generations, beginning in the seventeenth century and steadily becoming “younger”. The histories of these two very different languages are, of course, wholly incongruent, and in any case pastiche archaizing is fraught with theoretical as well as practical difficulties, to say nothing of how it is likely to turn off the reader. So I decided that all I could really attempt in the early chapters was a somewhat more formal English, tinged with the occasional archaism, and then cling to the linguistic modulations of the successive generations.

How successful I have been is for others to judge. What I can say, as someone whose first translation from the Hungarian appeared in 1967, is that I lived with this novel day and night for three months, breathing in the Hungarian and exhaling it as English, and that it as true to the original as I have tried to be to Hungarian culture all my life.

4 December 2009 | in translation |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.