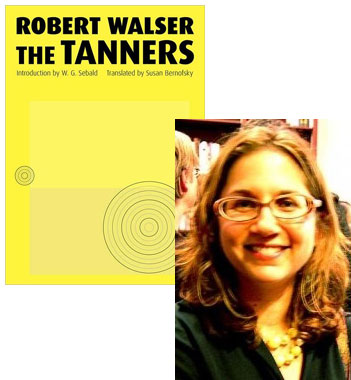

Coaxing German Literature into English with Susan Bernofsky

A few months ago, New Directions published a new translation of the early 20th-century German writer Robert Walser’s The Tanners by Susan Bernofsky; a mutual friend, knowing of my interest in showcasing literature in translation, suggested we should be in touch. I’m looking forward to reading The Tanners, and then late next spring New Directions will also be publishing Bernofsky’s translation of the story collection Microscripts; New York Review of Books Classics has also commissioned her to translate a separate batch of Walser stories. And Walser isn’t the only German-language author Bernofsky has translated into English. In this essay, she describes how “something that happened on the side” while she was working on her own writing has come to take a central role in her professional career.

Becoming a translator is the sort of thing that can happen to a writer who falls desperately in love with a foreign language and all the new possibilities it offers for saying things in different ways. There are so many gaps between languages, so many things that can be so deftly expressed in one language while they are almost impossible to explain in another, and the more conscious you become of these discrepancies, the more temping it becomes to start triangulating back into English, looking for ways to coax your own language into saying all these new things.

My first experiments with translation began when I was just starting out as a writer. I tried my hand at translating not because I had a grand plan for revolutionizing the English language, but because I was fascinated by what the foreign writers I was reading in German were doing in their texts as they played with the possibilities their language gave them. It’s possible to construct sentences in German that keep the reader waiting for the verb until the very end. What about in English? It’s possible in German to insert entire squadrons of complex adjectival phrases between the article “the” and the noun it belongs to. What can we do to make up for English’s inability to do so? I found that I enjoyed gnawing on problems like this the way some people enjoy crossword puzzles.

I never set out to become a professional translator. Translating was just something that happened on the side while I was preparing myself to be a writer, scholar and teacher, for the simple reason that I never stopped working at it. It was fun. People said they liked the stories I translated for them, so I felt encouraged to do more. It was a good way to act on the impulse I often had to show other people things I liked. For example, I became Yoko Tawada‘s translator just because I happened to stumble on a tiny one-page story by her in the Austrian literary magazine manuskripte that I liked so much I wanted people I knew to see it. After translating the story, I wrote to Tawada care of the magazine asking for permission to publish it, and by return mail she sent me another little story with a note asking me to please translate that one too.

Now Tawada has become an author whose work I translate regularly. She writes both in German and Japanese, and I collaborated with Yumi Selden to produce an anthology for New Directions, Where Europe Begins, that includes stories translated from each of her two languages. And just this year New Directions published Tawada’s beautiful novel The Naked Eye in my translation. The main character of The Naked Eye is a young Vietnamese girl who travels to East Berlin for a Communist youth conference before the fall of the Berlin wall. Kidnapped, she finds herself in Paris, where, unable to speak the language, she becomes a passionate moviegoer and falls in love with Catherine Deneuve. Since she can’t understand what the characters in the movies are saying, she makes up her own stories to go along with the images and intercuts them with the stories of what she herself is experiencing in Paris—reports that range from the surreal to dirty realism as she discovers what it means to scrape by as an undocumented alien. Each chapter of Tawada’s novel interacts in some way with one of Deneuve’s movies; the last chapter is entitled “Dancer in the Dark.”

I’ve been publishing translations for over twenty years now, and still love trying to hold two languages in my head at once. I’ve also been very fortunate in the books I’ve been invited to translate, particularly in the case the great Swiss-German modernist author Robert Walser. I’m currently at work on my sixth volume of his prose. This extraordinary writer was largely forgotten for many years, though there was a brief flutter of interest in the early 1980s when Susan Sontag championed his work, writing a foreword for the gorgeous collection Selected Stories of Robert Walser (translated by Christopher Middleton and others). New Directions has recently published Walser’s two early novels The Tanners and The Assistant in my translation, and in Spring 2010 will be bringing out a volume of his stories entitled Microscripts in conjunction with Christine Burgin Gallery. These late works by Walser include some of his most mysterious and challenging short prose—I think of these texts as the equivalent of Beethoven’s late string quartets. In his late work, Walser, the master storyteller, plays with the conventions of storytelling, often chopping up his narratives into odd cubist collages that tend to be hilariously funny as well as moving.

This winter I’ll be translating a new book of Walser’s early stories for New York Review of Books Classics—stories written in (and largely about) Berlin, which was already one of the most interesting metropolises in Europe in the first decade of the 20th century when Walser lived there.

Another translation of mine forthcoming from New Directions is the third book I’ve translated by Jenny Erpenbeck, the novel Visitation. (The two others are entitled The Old Child and Other Stories and The Book of Words.) Visitation is a little like a family saga, except that the main character holding the book together is a little country house rather than a person, and the family story is really the linked stories of several families that live in this house one after the other. The book is based on the history of a real house that was briefly in the possession of Erpenbeck’s family when she was a child, and the story she spins around it retells, in passing, the entire history of 20th century Germany—East Germany in particular. Family after family vacates the house (often precipitously) as one political upheaval after another turns German society on its head. And yet the generations of characters stick around long enough that we get a feeling for them as individuals—the book is compelling on a personal level and not just as an historical document. It also displays the haunting, lyrical style that has become Erpenbeck’s trademark. Her sentences coax the reader along until it feels as though the entire universe is made up of overlapping sentiments and stories.

The word “coaxing” is actually a useful one for describing the work I do as a translator. Making a voice work in English, making German work in English, making a sentence work even though it was originally thought in a different language: There are so many ways to tell a story, and when you translate you become highly conscious of how the most subtle changes in syntax or diction can produce substantial changes in voice and tone. Finding the right voice for a translation is often a matter of calibrating and recalibrating a sentence over and over, polishing it until it gleams in that particular shiny way that says “I am literature.”

3 December 2009 | in translation |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.