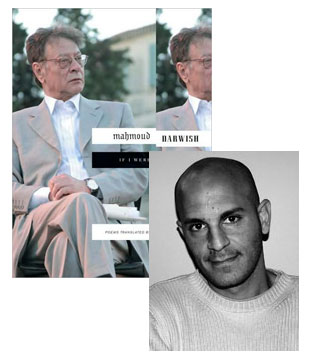

Fady Joudah & the Late Styles of Mahmoud Darwish

Here’s the opening lines from If I Were Another, a posthumous collection of the lyric epics of Mahmoud Darwish, as translated by Fady Joudah:

…As I look behind me in this night

into the tree leaves and the leaves of life

as I stare into the water’s memory and the memory of sand

I do not see in this night

other than the end of this night

the ticking clock gnaws at my life by the second

and also shortens the life of this night

nothing of the night or of me remains to wrestle over.. or about

but the night goes back to its night

and I fall into this shadow’s pit

I invited Joudah to discuss his connection to these poems, which span fifteen years towards the end of Darwish’s life, a time during which, as Joudah explains, Darwish began to feel that he had truly come into his voice… which is true, but as Joudah reveals, that doesn’t mean that voice wasn’t capable of changing even further…

It was 1983 when the great Greek poet Yanis Ritsos, introducing Mahmoud Darwish to a packed amphitheatre in Athens, Greece, first used “lyric poetry” to describe what Darwish’s art had embarked upon since an early age. But it took Darwish a few more years to believe that he has achieved a mastery of the lyric epic to a level he would not disclaim later on as he did with many of his earlier poems (and in that W.H. Auden strikes an echo). And so it was with the 1990 collection, I See What I Want, that Darwish had reached new heights with his lyric epic.

It was more than 10 years ago, while rummaging through my uncle’s library, during a visit to the UAE, that I came across Mahmoud Darwish’s most recent book then—Why Did You Leave the Horse Alone? (1996)—and immediately fell in love with its vision of memory, myth, and place, the personal and the universal. I can’t remember whether my uncle had a second copy, or he simply let me have the only one he possessed; had he not, I would have stolen it anyway.

Subsequently I went out and bought the two thick volumes that collected Darwish’s poems from 1966 through 1992. The last two poetry collections in the second volume were sister collections, composed entirely of lyric epics: I See What I Want (1990) and Eleven Planets (1992). Thinking about Darwish’s poetic shifts over the decades of his writing, I realized a few years ago how necessary it is to compile a collection that would bring together, from 1990 through 2005, in their entirety, a master-poet’s most mature lyric epics: If I Were Another.

Darwish would later claim that Why Did You Leave the Horse Alone? is the book that marked his “new works.” But it was Edward Said (in a beautiful essay in Grand Street, “On Mahmoud Darwish”) who, as Ritsos did before him, recognized an earlier shift in Darwish’s poetry. Said realized that since the beginning of the 1990s Darwish had already entered the realm of “late style,” an expression Said borrowed from Theodore Adorno’s essay on Beethoven’s brilliant late works. Darwish’s artistic achievement, Said explained, was reaching beyond historical finalities, beyond the “time of ending,” and into “what happens after the ending, what it is like to live past one’s time and place.” In particular, Edward Said emphasized the brilliance of Eleven Planets, and described the “strained and deliberately unresolved quality in Darwish’s recent poetry” as “an astonishingly concrete sense of going beyond what anyone has ever lived through in reality.”

But in reality, Darwish would make another turn in his aesthetic, expand his range, and delve deeper into his late style as he came face to face with death and his deteriorating body in 1998. Mural, the book-long poem in which Darwish writes down his language “to the meter of seagulls in the book of water,” and where he engages Death in a dialogue that has become immortal literature already (and was produced for the stage, and tours the world), comprises the heart of this new translation collection. Mural merges the self with its other in a contemporized Sufi aesthetic, and places Darwish’s life-long development of the poem as theatre in full view.

Still it isn’t just the development of the lyric epic in Darwish’s poetry that I was after. If I Were Another also emphasizes Darwish’s desire for dialogue in verse, an aesthetic evident also since his youthful days. And racing time and death, Darwish had work to do still in myth and dialogue. In 2005 he published his long poem, Exile: a quartet that concludes If I Were Another, and depends on dialogue between the “I” and its feminine other; the self and its companion as they walk back and forth on the bridge of being; the poet and his ancient, poet-shadow as they converse over and about ruins, elegy and affirmation; and, last but not least, Darwish himself in a conversation with his mirror-image friend, Edward Said, about exile and identity.

If I Were Another journeys with the reader through Darwish’s numerous and illuminating transformations of aesthetic and diction. As I reread the book today I realize how I myself have become another in its midst: as translator and as poet, as one bound to the limitations of individuality in time and place and as one free of them: simultaneity and illusion.

6 November 2009 | in translation |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.