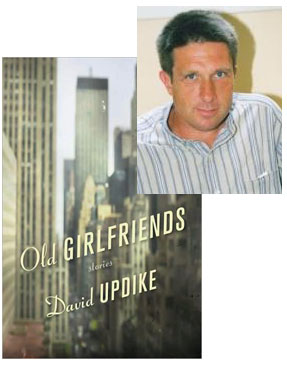

David Updike and the Fool’s Errand of “Araby”

After reading David Updike’s “Selling Shorts” guest essay this weekend, I felt like I’d been let in on a secret running through several of the stories in his latest short story collection, Old Girlfriends, an undercurrent of equal parts confusion and compulsion. There’s plenty of other things going on in these stories—”A Word with the Boy” and “Love Songs from America,” for example, tap into those moments when fathers realize they can’t protect their sons from the world, and how such moments affect their relationships with both sons and world—but even those Updike characters making a conscious effort to understand their emotional lives, like the in-analysis protagonist of the title story, find themselves stumbling through incidents they can’t quite get a grasp on, wondering how they’re going to make it through.

It may have been in high school that I first read the story, or maybe college, in the freshman writing class for in which I received a C on every paper I wrote and also for the final grade. And I must have carried a tattered copy of James Joyce’s Dubliners when I took a semester off two years later, and made my own ill-planned visit to Ireland, in the middle of January. I spent several lonely weeks in chilly bed and breakfasts, pubs where all backs seemed to turn toward me when I came in, after wandering for hours through the gray cold streets of Dublin with my camera and red backpack.

But whenever I read this short story, “Araby,” it struck a chord in me, echoed some of my own, deep childhood preoccupations: the stubborn slowness of time; the hopeless longing for inaccessible, older girls; the inability of the adult world to be of much use to me in my private, emotional quests. There was also the beauty of language, of words being used in strange and pliable ways:

“The cold air stung us and we played until our bodies glowed. Our shouts echoed in the silent street. The career of our play brought us down through the dark muddy lanes behind the houses where we ran the gauntlet of the rough tribes from the cottages, to the back doors of the dark dripping gardens where odours arose from the ash pits, to the dark, odorous stables where a coachman smoothed and combed the horse or shook music from the buckled harness.”

I could hear this music, knew well the glowing bodies in cool air at dusk on autumn afternoons, the air smelling of burning leaves. And then, the crux of the matter, girls like Mangan’s older sister, impinging herself on our simple, boyish needs: “She was waiting for us, her figure defined by light from the half opened door. Her brother always teased her before he obeyed and I stood by the railings looking at her. Her dress swung as she moved her body and the soft rope of her hair tossed from side to side.”

The soft rope of her hair! Her dress swung as she moved her body! I, too, had been haunted by the clothes and mysterious movements of older sisters—their distant carelessness, vague awareness that they were being noticed, willingness to draw me toward them.

And then she speaks to him, and mentions the fair—Araby—regrets that she can not go and carelessly suggests that, if he goes, he bring something for her, a gift, and he is suddenly lost in this foolish ambition. But the adult world maddeningly intervenes: His uncle won’t come home to give him his blessing and a little money with which to buy the imagined gift; outside, it is getting dark, and the clock is ticking, and when his uncle finally does come home, he has forgotten, laughs, then finally presses a coin or two into his hand. But by now there is a doomed air about his enterprise: the slowness of the train, the lateness of the hour, and when he finally gets there, the emptiness of the hall, the dwindling remnants of the fair, and the sale girls, indifferent and taunting. But there is still hope, still something to buy for her—vases, and flowered tea sets—or maybe something else that he can afford. But when the girl asks if he needs any help—the moment when he could have found something, anything—he turns inward, inhibited and shy, and sabotages himself, “No, thank you.”

He lingers a little longer so as not to appear a fool, but knows all is lost, and then the tragic epiphany: “Gazing into the darkness I saw myself as a creature driven and derided by vanity; and my eyes burned with anguish and anger.” I could see myself as this small, tragic figure, skulking back to the oppressive loneliness of his uncle’s house. I had more than once set off on some fool’s errand in pursuit of a girl’s notice, and almost as many times found myself gazing up into some hazy void where her image still burned, like smoke, wondering what had just happened. What I didn’t know was how often the small and ancient tragedy would repeat itself, like a recurring dream, in the years and decades yet to come, and how little I could do to change it.

photo: The Boston Globe

6 September 2009 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.