What Julie Rose Adds to Victor Hugo

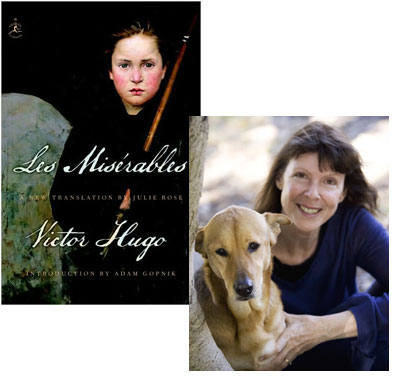

When I began conceiving of the “In Translation” series of essays last year, one of the first translators I wanted to invite was Julie Rose, as her mammoth new English-language version of Les Misérables had just been released. I finally took the opportunity earlier this year, when I learned that she was among the finalists for the French-American Foundation’s annual translation prize; we began corresponding, and eventually a gap came up in her schedule (as she notes early on, she’s kept very busy translating modern French literature!) when she was able to share her thoughts on tackling Victor Hugo’s most famous novel. The appearance of this essay coincides with Rose’s first visit to the United States; in fact, if you follow Beatrice on Facebook, early next week you’ll get the inside scoop on a small gathering we’ll be having in New York City. I’m looking forward to meeting her in person, and I hope I’ll see some of you there!

I have four new translations out there on the shelves at the moment, all published in the last fourteen months.

The most mammoth of these is Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables, published by Random House (New York) and Vintage (London) in hardback last year—now out in paperback. At the opposite end of the spectrum is André Gorz’s slim but relentless letter to his wife of 58 years, Letter to D., published by HarperCollins (Australia) last year and by Polity Press in the US and UK recently; and French-born, Sydney-based Catherine Rey’s Stepping Out, an autobiographical portrait of the artist as a young—and not so young—woman, published by Giramondo (Australia) late last year.

The fourth book, Film World, is a collection of interviews with celebrated filmmakers recorded over decades by French film critic Michel Ciment. That was an interesting project, since Ciment had recorded a number of the interviews originally in English, which he speaks, before translating them into French. I then had to translate them back into English, without, in most cases, anything to go by, since the tapes had been trashed and most had never been published in English before. It was fun ‘playing’ 25 wildly idiosyncratic cinematic geniuses.

There would normally be a splendidly hybrid book by cultural critic Paul Virilio, as well. He turns out one a year and I’m never too far behind; though not yet out, University of Disaster is coming soon. And I’ve just finished a draft of an intricate theoretical work by Jacques Rancière, Politics of Literature. I myself am dazzled by the scope of this list of fabulous books. Hugo, Gorz, Rey, Ciment, Virilio, Rancière: writerly biodiversity in action.

Such a list presents vast differences in style, emotional register and temperament, context and resonance and intellectual tone—all those qualities that go to make the thing we call ‘voice’. Some people talk about texture, flavour, music, taste, colour. These are all sensory metaphors for the same thing. I prefer to call it ‘voice’ to suggest the theatricality not only of the embodiment of personality in writing in the first place, but the whole performance of re-embodiment that the process of translation entails. Translation is rewriting—as someone you imagine the writer to be.

A writer’s ‘voice’ in this sense is as unique as the thing produced by their vocal chords, no matter how codified shared language and the rules of writing might be. It is ‘voice’ that a translator worth her salt is always trying to mimic.

Translation as an art is an art of listening that means getting into ‘character’ and staying there, convincingly, from start to finish. In so doing, of course, you produce your very own distinct voice, with its very own timbres and energies. Which is one reason why re-translating is a potentially endless field. The original text stands immutable, but its potential translations are potentially infinite.

For me, there’s a golden rule here which is that, the more distinct that ‘second’ voice—the voice that you the reader, who needs the translation, receives—the more intensely and successfully I, who don’t need the translation, have managed to ‘get’ the original.

The ‘successful’ translation is the one where I, the translator, am completely invisible. A translator’s glory lies in their own disappearance. Nothing could be more satisfying. For others. Of course, every word is mine as much as his or hers. It is a double act, after all.

For I’m not re-writing—translating—in a cultural vacuum, any more than the ‘original’ writer is; and I’m not a blank, either. Getting under the skin of a writer, of a work, will involve using my own tools. I love precision and accuracy and have been accused of wielding a scalpel. But inventiveness is every bit as important in a successful translation. Inventiveness is part of the acute receptivity, otherwise known as empathy, you need to embody someone else’s voice.

Voice encompasses a whole work, from personality to meaning. ‘Hearing’ the other person’s voice, profoundly, viscerally, and dredging an answering voice up from out of the depths is the joy of the job.

And so, obviously, every job is completely different. The challenge with Gorz, for instance, was to steer the same tense, taut course he steers between exuberance and anxiety in this rare tale of happy life-long conjugal love written all-of-a-piece, in a kind of unblocked spurt, against the louder and louder ticking of that metaphorical clock.

Translating it involved a tremendous effort of concentration to see that both the intellectual fineness and the emotional urgency were held together with as much poise as Gorz effortlessly produces. I could have said, as French effortlessly produces. Because French allows you to deliver emotion with a kind of elegant intelligence that isn’t available in conversational English. To be readable in English, that is, to be as fluid and fluent as this famous intellectual’s ‘conversational’—anecdotal—French, it wasn’t possible to be doggedly literal in the sense of religiously following syntax and formulation. I had to exercise the translator’s robust liberty to depart from the text wherever necessary—in order to remain faithful to it. We are, of course, talking very small degrees, here. This is not the place for the great departures of adaptation freighted with commentary.

Adding, subtracting, multiplying, dividing: maybe translating is also doing math, musical math. If so, additions need to be kept to a minimum according to the requirements of intelligibility, subtractions even more so, but the chopping up of syntax and the multiplying of sentences is often essential.

With Victor Hugo’s monumental Les Misérables, I felt the need only very occasionally to add, for reasons you may well imagine, but never to subtract. In the description of the Battle of Waterloo, for instance, when Napoleon refers to his nemesis, the Duke of Wellington, as ‘ce petit anglais‘, I couldn’t stop my Napoleon from adding a noun: ‘that little British git’. Call me a jaded modern Australian, but for me, ‘that little Englishman’ just didn’t get the withering contempt with which the mere descriptive ‘anglais’, coloured by the ‘petit’, was charged in the Hugo. The Victor Hugo I came to know, a man with a great sense of humour, would have laughed, I like to think.

Translators of Hugo traditionally never add, they subtract—and rather cavalierly at that. Certainly the exact nature of Hugo’s feel for the idiosyncratic and the particular, his celebration of sheer excess, is lost in the process. That’s the conclusion I reached as I read the two best-known English translations—Charles Wilburs’ 1862 version and Norman Denny’s from 1976—while I was working through the first and second drafts of my Misérables (precisely to make sure I left nothing out).

I’d never read Hugo’s novel before translating it. This turned out to be lucky, because one of the things that kept me going, at least on the difficult first draft, was the need to know what happens. (You don’t need to be an expert before you translate something, you acquire expertise in translating it. If I’d read it before, I may never have had the courage to go on…) I raced toward the finishing line on that first draft (and sobbed mightily when I got there), revelling in what turns out to be a gripping page-turner of a thriller embedded in a much larger work about everything, written with equally compelling exuberance and gusto—and sheer delight in language.

It took me three years and three drafts to bring the translation to completion. I always do three drafts of anything, but usually race through the first to seize the tempo, the rhythm, the unique music of the piece. Of course, that wasn’t possible here. But the slower pace gave me time to really wrestle Hugo to the ground—every word and every comma—and then pick him up again and dance.

Keeping pace with the great Victor also meant walking for miles every day with my dog Poppy, rain, hail or shine, much like Hugo himself. It also took three other major translations—all Virilios—as I found I couldn’t go on without a few breaks from the blazing intensity of Hugo’s prose.

That prose, which Rimbaud once described as ‘pure poetry,’ was a shock. Far from faded, stale, overblown—the things I’d feared—it felt amazingly fresh, sharp, even modern in its often staccato thrust. The muscularity of Hugo’s rhythms, the endless tonal and discursive shifts, all handled with virtuoso ease, the prescience and brilliance and even, at times, sheer bizarreness—and occasional corniness, such is Hugo’s greatness—were downright tonic.

Hugo, who’d spent many years by this in the Channel Islands and read English, didn’t much like the Wilbur. It drove him to declare that translation was censureship, a spin on that tired old chestnut about translation as betrayal. Wilbur is, in fact, elegant, just a little tarnished now by time; Denny’s translation is pleasurably fluent, but it’s not Hugo.

What I wanted to do was come up with a Hugo for our time—by staying absolutely true to Hugo. If anything, I risked being overly reverential. Reverence is good, too much reverence is enfeebling. It may be a very subtle distinction, but you can hear it immediately in a translation. We translators need to be humble and cocky at once; we need to relax. For translation is an intuitive art; sometimes it requires a bit of fiddling to be true, sometimes a faith-full fidelity. It’s time we heard less about what is ‘lost in translation’ and more about what might actually be gained.

© Julie Rose

1 September 2009 | in translation |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.