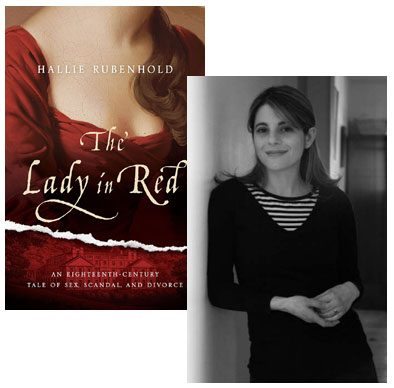

Hallie Rubenhold Rediscovers the Worsley Affair

Beatrice is perhaps best known for its focus on fiction; however, my taste in romance novels is influenced in no small degree by an interest in late-eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century British history, so biographies of figures from that period will almost certainly catch my eye—such was the case with Hallie Rubenhold‘s The Lady in Red, which UK readers may readily recognize as Lady Worsley’s Whim. But how did Rubenhold hit upon one of the most notorious sex scandals of the 1780s as her subject? It began, she explains, with a painting…

Call it perverse, but as a historian, I’ve never been interested in telling the epic stories. Yes, I find the big ‘set pieces’; the battles and incidents of court intrigue fascinating. I’m enthralled by monarchs and presidents, wars and turning points, but I’m also strongly of the belief that true history lies in the details. It’s the bits that have been left out of the history books that are crying out to be told. It’s the voices that have been silenced or never heard before which require attention. My gut instinct has always been to mine the archives and dig out the rare gems, which is how I came across the story of Sir Richard and Lady Worsley.

At first I found it amazing that no one had written a book about them; Lady Worsley’s portrait, painted by Joshua Reynolds (c. 1780), is perhaps one of his most striking and bold works. The full-length painting (which now hangs at Harewood House, a stately home in the north of England) features its subject adorned in a blazing red riding habit, her hand tightly gripping a riding crop. Needless to say, her defiant and unconventional stance raised as much comment in the eighteenth century as it still does today.

It seemed odd to me that although so many eyes had examined this image, no one had been compelled to discover the story behind it. In fact, very little at all was known about the Worsleys, and what I did find only piqued my curiosity further. According to the portrait’s catalogue entry, Lady Worsley, her husband, and her lover, Captain George Bisset had been embroiled in one of the greatest sex scandals of the eighteenth century.

In 1781, Lady Worsley and her amorous Captain had run off together to London. A furious Sir Richard immediately retaliated by bringing about a suit of Criminal Conversation, a now defunct legal action where a husband can sue his wife’s lover for ‘damage to his property’. The trial was held in open court, an arena in which Sir Richard hoped to publicly disgrace Bisset and claim an astronomical £20,000 for the despoilment of his wife.

Unfortunately for Sir Richard, the scheme back-fired horrendously when all of the Worsleys’ unorthodox boudoir secrets were revealed. The details were jaw-dropping and would even raise an eyebrow or two in the 21st century. The newspapers pounced on the story, and in the weeks and months to follow, London’s entrepreneurial publishers cashed in on the insatiable public demand for stories about Lady Worsley’s legendary ‘appetite’ and Sir Richard’s questionable sexuality.

But the story (or rather stories, as Sir Richard and Lady Worsley’s lives take divergent paths in the trial’s aftermath) is not as straightforward as this. While rummaging through the archives, searching for the smallest shreds of material, I was constantly amazed by the strange twists in this tale; Worsley’s brush with the events leading up to American Independence, the attempts at blackmail, a possible infanticide, the adventures through Greece, Turkey and Egypt, and Lady Worsley’s entanglement with the French Revolution. The narrative, which soon ballooned into a Gothic-Romantic epic, just seemed to become “curiouser and curiouser.” “You’re never going to believe what I’ve found today… honestly, you just couldn’t make this stuff up,” I found myself saying over and over again.

The more I delved into the Worsleys’ sordid histories, the more it became apparent to me why no one ever did attempt to write a book about them. Their tales were so outrageous, so shameful to later generations that several well-meaning individuals had attempted to blot out their names and deeds. Vast amounts of personal correspondence had been destroyed, though a large amount of legal documents and newspaper reports managed to escape the flames. Discovering this made me want to tell their story all the more, to take them out of the shadow of moral censure and to allow a more forgiving modern society evaluate them for what they were; human.

24 August 2009 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.