How “The Scarlet Ibis” Helped Peter Neofotis Find His Voice

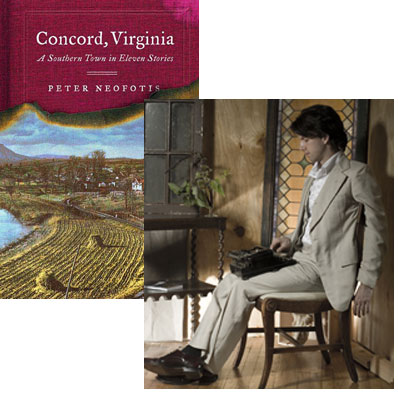

For the last three years, Peter Neofotis has been performing his short stories in various venues around New York City—all of them set in a fictional community which gives his debut collection its title: Concord, Virginia: A Southern Town in Eleven Stories. As I was reading the first stories, given that one of them is about a Korean War veteran fending off an inquisitive reporter’s attempts to get him to say something inspiring for the young men heading out to Vietnam, I made assumptions about Neofotis’s age that proved completely off base; turns out he’s still on the young side of 30. And yet his voice is already clearly identifiable as his own, and it’s unlikely, once you’ve read one or two of his stories, you’d mistake any others you come across for anybody else’s. When I asked if he would discuss his literary inspirations, he picked a story that helped shape both his writing and his performances.

I have just reread James Hurst’s “The Scarlet Ibis,” and once again, it has made me weep—just as it did when I read it in my high school freshman English class ten years ago. I remember the entire class—a very mixed bunch in a public high school—had been moved by the story. Mrs. Lynda Gray, a terrifyingly brilliant teacher, even cracked a tear when she read a few lines from its pages:

“It’s strange that all this is still so clear to me, now that that summer has long since fled and time had had its way…”

The tale behind the “The Scarlet Ibis” is as lonesome and beautiful as the story itself. James Hurst wrote it in his 30s, a few years after taking a job at a bank, to express his grief over his failed career as an opera singer. And though it is his only writing to ever receive national attention, it was a phenomenal success: first published in The Atlantic Monthly in July 1960, it won the magazine’s annual fiction prize then, as Hurst has commented, “took on a life of its own” and has been republished in several anthologies. Often, it is used to teach symbolism. For the death of the stray scarlet ibis foreshadows the death of the narrator’s frail but wondrously lucid brother Doodle.

“the sick-sweet smell of bay flowers hung everywhere like a mournful song…”

I loved the story so much that while a high school senior, I memorized it. A few teachers then asked me perform it for their classes. One student—who had made fun of me in the hallways, because I am effeminate—approached me in the hallway a few days after seeing my rendition. Telling me it was “amazing,” he then reached out and shook my hand.

“I did not know then than pride is a wonderful, terrible, thing, a seed that bears two vines, life and death…”

And so, years later, when I was writing my own short stories, I submitted one to Greenwich Village’s Cornelia Street Café and asked if I could do a reading. My story, “The Abandoned Church,” like the “The Scarlet Ibis,” was a story about a death—which served as symbol for the fear and hopes of an aspiring artist as well an expression of grief for a friend and teacher who had just passed away. When the café curator called me and gave me his OK, I’d been given life. I started memorizing my story immediately, bought books on acting and speech, and every night would practice the script, pulling out the tools I had learned in memorizing Mr. Hurst’s masterwork. Every night for five months, I practiced that one story, often slapping myself when I did not get it right. And from my first performance of “The Abandoned Church” started the saga of shows that I have been performing regularly since then, the first 11 scripts of which are being now published as Concord: Virginia.

“Even death did not mar its grace, for it lay on the earth like a broken vase of red flowers, and we stood around it, awed by its exotic beauty.”

David Plante, my writing professor, has often told me that what he most admires about my stories is that I cry from some deep wound. Well, the narrator in James Hurst’s “The Scarlet Ibis” cries out from one of the most human wounds in the most resonating and honest voice. He was given something special. Something very sensitive, primordial, yet faithful. And though he nurtured it a great deal, he pushed it too hard out of his arrogant pride to be accepted in the material world. So he murdered his gift. Such murders, whether among brothers, parents and child, or artists, are all too common in the modern world. For we all want to be loved and admired, if not for ourselves, for the people and things that surround us.

And “The Scarlet Ibis” confesses this sin of pushing those we love too hard and letting ourselves be pushed as a great warning, one that I am continuing to learn but so far has served me very well. That he does it in the humble form of a short story is a wonder and testament to his sincerity. The result is a work of art of such stunningly beauty and vividness that it creates literary lightning, as powerful as the bolt that shatters the gum tree “like a Roman Candle” in the story’s final pages. The boys are running through the rain. Doodle, begging his brother not to leave him in the storm, falls behind. The narrator, turning back, then finds his brother, Doodle, bleeding to death under a red nightshade bush.

“For a long time, it seemed forever, I lay there crying, sheltering my fallen scarlet ibis from the heresy of rain.”

1 July 2009 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.