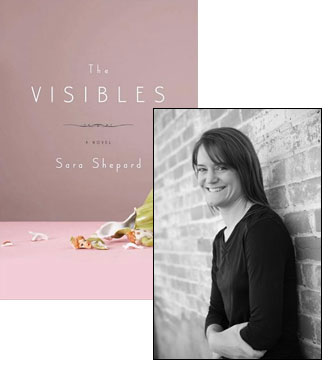

What Sara Shepard Talks About When She Doesn’t Want to Talk About Her New Novel

I’m still in the middle of—and very much admiring—The Visibles, the first “adult novel” by Sara Shepard, a writer who already has a strong track record with YA fiction. In fact, when I first approached her to write an essay for Beatrice, I suggested she discuss her transition from one market to the other—and though she gave that subject a go, what she ultimately found herself writing was something much more personal.

Those who have read The Visibles often ask, “What inspired you to write this story?” It’s a fairly common question—I get it for my young adult novels as well—but this time around, it trips me up. The information I think a lot of people are looking for makes me uncomfortable. The Visibles is about a girl coming of age in Brooklyn and Western Pennsylvania, DNA, secrets, prejudice, cancer, and depression—and the depression part of the novel springs from incidents in my own life. But it’s not exactly something I want to get into.

Fiction and memoir are two different things, obviously, but as a fiction writer, I can’t help but draw from what I’ve experienced firsthand. When reading someone else’s novel, I similarly wonder why the author chose to go in such-and-such direction, when there are so many avenues from which to choose: Is it because she’s drawing from her experiences? Did she have a husband who fathered a child with someone else? Did she have a wayward brother who’d been molested by a family friend? It’s not always the case, of course: I’ve written enough fantastical plotlines—in my young adult series, Pretty Little Liars, anything from student-teacher affairs, near-fatal blindings, hit-and-run accidents, and appearing and disappearing dead bodies prevail—to know that events need not happen to you for you to make them your own. You approximate, you empathize, you work the passage over and over until it feels right. The nut of The Visibles didn’t emerge from some sort of cosmic abyss in a bolt of blind inspiration, though—it emerged from a personal experience. Something I’m reluctant to talk about when someone asks me that question after they’ve read the novel.

I was very close to it back when I was writing the first draft of The Visibles. Back then, the book was set in the Outer Banks of North Carolina, and Summer Davis, the main character, was in her thirties with two children, teaching biology and falling in love with an awkward but precocious student. Flashbacks to Summer’s previous life in New York, caring for her ailing father, kept poking their way in, invading each passage. The flashbacks, which related to my own life and were probably a therapeutic way by which to work it out, began to take over the novel, more or less stealing the show. I used up all my energy to write them; I took a week off work to pound out the flashback section so that I could be done with it and never return to it again. Following Summer’s flashback to its end was cathartic. I’d written it down; I’d gotten it out of my system.

I liked those passages, though. I liked them, in fact, more than I liked the rest of the novel. They were real, they said something. I came from a very strong emotional place when writing them, and that felt more authentic to me than the rest of the book. As seasons passed, I wrestled with that version of the novel, trying to marry its troubled, indolent front story with its sharp, raw back story. Even the writing styles of the two sections were different. I spent months deconstructing the book and setting off in different directions, but nothing worked. It was like I was a kid, pulling a pair of pants from last year and realizing they now come up above my ankles: the novel was something I’d outgrown. After a while, I abandoned it and started working on something else, a story set in Brooklyn in the early 1990s about an imaginative and melancholy teenager wrestling with her mother’s apathy and subsequent abandonment. I would start fresh. All remnants of that previous novel were gone.

But the problem is, unlike my young adult novels, which are outlined to within an inch of their lives, I had no idea where I was going with this story, simply following it along and seeing where it went. And there I was, writing happily, when that same back story crept in again. Except this time, it was the front story. Problem was, it felt right for this book. The illness fit Summer’s father, and caring for him fit who Summer was and shaped who she would become. It was as if I’d written the situation before I met the characters. So what could I do but run with it? Time had passed, after all. I was no longer as close to my own experience; I’d gained needed perspective. I could now deal with it in a clear-headed way, looking at the events closely, changing details, reinventing the situation entirely so that it was now about my characters and not me. The illness became something very unique to Summer’s father, the symptoms and magnitude and treatment all his own, and Summer’s reaction and subsequent choices (or, as it was, subsequent avoidance of choices) all her own. I was able to let go and allow the novel’s characters to take over and change it to what it became. And it worked, I think. Except now that the book is out in the world, I get The Question.

What made you want to write this book?

This leads me to questions of my own. By having written this book, am I obligated to share where the idea came from? What gave me the right to plumb and exploit what happened, anyway? What do writers have rights to, and where’s that line that shouldn’t be crossed? For some people, does that line not exist? This wasn’t my story to tell. It happened to me, but it happened to other people, too, many people far more directly. Laying claim to it, parsing through its details with readers, feels like an invasion of privacy, which is probably why I tried to change as much as I could for The Visibles, holding on to the feelings it evoked but altering every single detail.

And even so, I still wonder if all my efforts were too transparent—it’s like the announcement at the beginning of a juicy true-crime show: Names have been changed to protect the innocent. The innocent people, if watching, certainly know it’s about them, don’t they? And how about the innocents’ families, friends, acquaintances, people who may have heard rumors here and there—is it easy for them to see through the ruse, too? Who gets hurt if a story veers too close to fact? If a story is told in a way that’s meaningful—if big questions are asked, if characters learn and change, if all those parties affected come out stronger and healed in the end, does it make it okay?

It’s something I’ll never really know and something I’ll always have trouble with. But I want to believe that something good came out of writing it down and turning it into the book it became. So when I’m asked that question, I usually gloss over that answer, concentrating on something with which I feel more comfortable. Like the other inspirations I took for the novel, things I’m giddy to reveal: Summer’s great-aunt, Stella, for instance, who is fiercely independent, convinced that the afterlife is like an episode of The Price Is Right, and obsessed with eBay and velvet paintings of deer and Frank Sinatra, is an amalgam of every wonderful family member—my grandfather, my grandmother, my mother, my aunts. Just like the troubling events that inspired the crux of this book, I felt that I needed to tell Stella’s story. I needed to create her and get her out into the world, and I tried to render has as carefully and as truthfully as I could. And that, I suppose, is the best I can ever do.

14 June 2009 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.