Emily St. John Mandel and the Allure of Languages

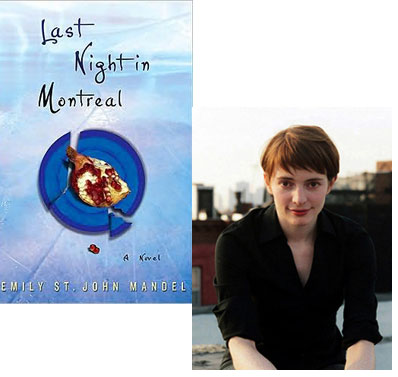

I’ll be introducing Emily St. John Mandel as she reads from her debut novel, Last Night in Montreal, at the Mercantile Library (17 E 47th St) this Wednesday night at 7 p.m. The story unfolds like a mystery as Eli, a perpetual grad student specializing in languages that nobody speaks any more, tries to understand why his girlfriend, Lilia, just up and vanished from Brooklyn—and though Michaela, an exotic dancer in Montreal, can tell him, she’s holding back the information until he tells her something else about Lilia’s past… which we also see from her perspective.

(You’ll also want to come hear Greg Ames read from his debut novel, Buffalo Lockjaw—and you can read my Q&A with him Tuesday over at Maud Newton’s website, but if you care about great writing, you’re probably reading that already. Right?)

Do you share Eli’s fascination with extinct languages? Is there one where the disappearance strikes you as particularly poignant?

I do share Eli’s fascination with extinct languages. What strikes me as particularly poignant isn’t so much the loss of any one specific language, but the way in which so many of them die: in the end, after decades of gradual attrition, it often comes down to one last speaker. When that last speaker dies, the language dies with them.

There was a particularly heartbreaking quote in The New York Times that I read a few years back—the reporter had gone to the Amazon to interview Natalia Sangama, the last woman who spoke a language called Chamicuro. She told the reporter, “I dream in Chamicuro, but I cannot tell my dreams to anyone. Some things cannot be said in Spanish. It’s lonely being the last one.”

You lived in Montreal briefly before coming to New York. Was your experience there as disheartening as Eli’s or Michaela’s? (And while we’re on the subject, how’s your French?)

My French, regrettably, is virtually non-existent, although I’m very good at saying “I’m sorry, I don’t speak French” and “A bowl of cafe au lait, please” en francais. I consider this both a personal failing and a gap in my education; French is a required subject in Canadian schools, but I was homeschooled as a child and never picked up the language, and I grew up in a region (the west coast) where almost no one speaks French. When I arrived in Montreal, I’d only heard French spoken in passing maybe five or six times.

As the casual reader of my novel might guess, my experience in Montreal wasn’t overwhelmingly pleasant. I’d been under the impression that Montreal was a bilingual city and that therefore I could get by in English for a few months while I learned French. This turned out not to be the case.

What are you working on these days?

I actually just sold my second novel to Unbridled Books, which is tremendously exciting; I’ve loved working with them on Last Night in Montreal, and it’s a joy to have the opportunity to work with them on a second project. I’ve been working on revising the second novel; it’s called The Singer’s Gun, and it’ll come out in spring 2010. I’ve started writing my third novel, but only barely.

11 May 2009 | interviews |

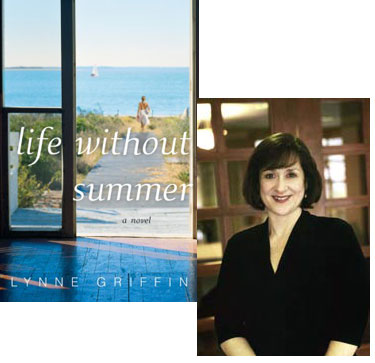

Lynne Griffin: Literary Mother-Daughter Time

In this special Mother’s Day essay, Lynne Griffin discusses the ways books have helped her bond with her daughter over the years, up to and including the writing of her debut novel, Life Without Summer.

From the time she was able to sit her little body upright, my daughter held tight to a book. I can still picture her in that baby carrier pretending to read her first board book, Teddy’s Garden. As a family educator, I’d been telling parents for years that a love of reading can and should be nurtured. While I still believe this to be true, for my daughter, the passion for books is as innate as the color of her eyes.

In the beginning, I’d capitalize on her interest in books by placing her in a stroller at naptime, thinking whether she slept or didn’t, I’d be able to buy some bookstore or library time. I could poke around collecting titles for my to-be-read list. Invariably she’d resist sleep, instead intent on “reading” her own book—turning the pages delicately, always with the care of a librarian—giving me all the time I needed to make my selections.

In her early childhood, late in the afternoon, I’d act as if my number one priority were good role modeling, when in fact I was merely in need of a break from the rigors of parenting a little one. I’d tell her it was time to collect a stack of books and meet me on the living room couch for some quiet time. In minutes, she’d be as engrossed in her picture or chapter books as I was in the latest hardcover novel I’d purchased.

Until she was a self-sufficient reader, my husband and I would read countless books to her; always before bed, on long car rides, or during dinners that involved foods she didn’t care for. Reading provided an almost magical distraction. We became fans of library visits, books on tape, and book swaps with family and friends.

Like every good parent, I couldn’t wait for the day when she would display her talent for independent reading. Though as she gained skill—always holed up in her room, or parked under a tree, even walking through the house lost in a book—I feared I was losing something. Lovingly crafted, ours was a relationship made closer because hard working authors carefully chose the words placed on those pages. I wasn’t ready to relinquish our special bond made possible through reading together.

10 May 2009 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.