Christian Moerk and the Trouble with Inspiration

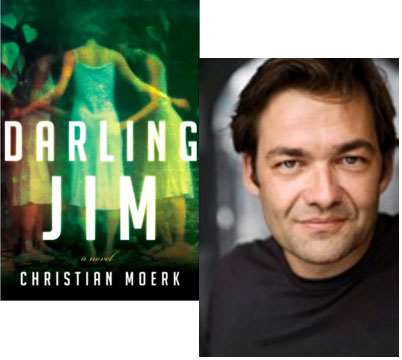

Earlier this week, over at GalleyCat, I had the privilege to post an original Howard Chaykin illustration—a representation of an image described in the final paragraphs of Darling Jim, the debut novel from Christian Moerk. And now, I get to present Moerk’s behind-the-scenes perspective on everything that led up to the words that inspired that drawing. I hope his story will lead you to, well, his story.

I’ve always had a hard time relating to the notion of “inspiration,” in which writers by the very act of going to work are supposedly gifted with something that descends upon them from above and becomes a holy entity of which others should be appropriately respectful. C’mon, you know exactly what I mean: writers looking heavenward while they drone on about where their “inspiration” leads them, or how finishing a book has made them grow as human beings. It’s as if this ethereal propulsion drives their fingers and not the other way around. “Inspiration” is like a handsome dinner guest you can’t start eating without.

That’s bunk, of course. So is the phrase “my process,” unless you develop photos for a living.

The problem for me, I think, lies at the heart of what “inspiration” is supposed to be—for many, the very residence of “creativity” (another close second in the c’mon-shut-up category). So in discussing Darling Jim, I’d like to explain, as honestly as I can, how the work itself sneaks up on you and becomes more important than what the writer has to say about it. To be blunt: it’s the story, not the writer, which is supposed to be interesting.

I learned this early. Years ago, I’d gotten a brief writing gig for RTE, the Irish national public TV network. It was a miniseries about human trafficking set in Dublin, and I was one of several contributors. As such, I was mostly ignored. So I began walking around and looking at people, houses, social patterns, while listening for different timbres in people’s voices. I’ve always been a spy. I began imagining a story taking place behind the walls of the rough-looking pebbledash storefronts on Dublin’s north side. Is that “inspiration?” No. It’s a notion. An idea. A meeting B. There’s no life in it yet.

I missed my flight back to the States and couldn’t afford to change the ticket, so I was forced to wait another week. A movie director friend offered that I come down and spend a few days in West Cork at his country house. I took the train. In my pocket, I had a small news clipping about an unresolved triple death inside a small house earlier that year; an elderly woman and her two nieces had died mysteriously. A tragedy, people said. I couldn’t stop thinking about what might have happened in that house. Behind the dirty pebbledash wall. I could see it clearly. To me, it wasn’t a simple case of suicide, as the cops later determined, but the inevitable result of one beguiling man weaving his stories all over the countryside. I could see “Darling” Jim clear as day, getting off his 1950 Vincent Comet racing machine and winking at whomever came by, be it man or woman.

I suppose you’ll tell me that, right then and there, I was struck by a flash of “inspiration.” Because none of us can really explain correctly where the transfer takes place between notion and story. It’s like a dried-out bone growing muscle; a movie being reeled backwards. Maybe that’s why people yammer on about “the process” rather than letting it do its work, because it’s inexplicable. That’s why we clutch at clichés like “creativity.” Fair enough. I had something more than an abstract notion. But it lay at the bottom of the ocean. I hadn’t fished it out yet. Funny how “inspiration” never lends you the net.

Jim was waiting for me at the train station, too. In the flesh. I struggled with my bags while this kid—no more than twenty, I think—roared past on a black Yamaha and made the cabbies shake their heads. Bits and pieces are all over the ground if you open your eyes and pick them up. Lest you miss my point, I’m not trying to say there’s no joy or thrill in that strange moment when a stray event becomes a coat hanger for an entire chapter—because that feeling where lead turns to gold is all that I live for. But it comes from work, not from talking about work. All I mean is that I, at least, decided to be greedy about it: I sucked up every sight, sound, and smell. I filled out a fistful of those little black notebooks with mostly nonsensical ramblings, out of which a few good ideas finally tumbled onto the paper. I liken writing to panning for gold (another endevor where “inspiration” gets you kicked off your lot and deeply in debt): You have to dig and wash your way through riverbeds filled with mud to get a small bag of the yellow stuff. But that’s the point.

My friend the director was lovely, but also in the middle of prepping another film, as I recall, so I once again trudged around the surrounding countryside, much like my antiheroical main character Niall ended up doing in the book. I felt like the stranger I was. Kids walking past on the sidewalks of Castletownbere often spoke Irish rather than English. I ingested this alien discomfort like a ham steak, chewed on it, and used it as an integral part of what “Darling” Jim Quick does to the townsfolk. He becomes their movie star fantasies writ large. He turns the small-town yearning on its head. I like the even exchange between what I put into the work during this time, and what “inspiration” decided to yield in return. I spent lots of time, and results slowly formed in my notebooks. Only very gradually, I began to write more than a notion. I was now writing a story. Don’t call it a book yet. It’s not anything until the words THE END. And even then, it’s still more a story than anything. That’s why I prefer being called a storyteller rather than an author. Less affected. Less isolated. More to the point. And it confers no specialness on me, but only on the characters. Which is where it properly belongs.

I returned to the small fishing village and spent several months holed up in an even tinier bed-and-breakfast. The three sisters Aoife, Fiona and RóisÃn had arisen from my watching the locals zooming past on the way to school, from the pub, and just plain hanging out. Really, people’s voices slithered right into my right hand and onto the page. Not by magic. Not by waiting for the handsome dinner guest. This transference happened because I was willing to forget myself and trust that these people’s authenticity wouldn’t seem jarring if I dared to replicate it fictionally. Is a decent ear part of “inspiration?” Perhaps. But, again, nothing happens if you sit and wait. Because voices are fleeting.

I wrote out a 90-page treatment that served as my chronological spine throughout. Hell, “inspiration” would have hated that. Dude’s a machine, it would have said. He’s cheating himself of my mysterious gifts. He doesn’t trust that I’ll shower him with manna. He’s a heretic. Not really. But having such an underlying row of coat hangers gave me the confidence to let other things really rip, which I would have otherwise obsessed about; I could now focus entirely on differentiating the Walsh sisters’ tone of voice, placing the reader slap bang in the middle of town, and integrating ancient folklore. I loved writing Darling Jim at that point more than any other precisely because I’d spent enough time to be bored with all my daily rituals. When I can forget the “art” part of it (another word I have trouble with in this context; any artist who needs to call themselves that forgets how that’s the audience’s job) and just write the damn story, I’m happy.

Sure. I have rituals, which must mean that I believe in more than cold facts. But of course I do: Three cameras per research trip. No driving, if it can be avoided. Politeness. And tons of unhealthy snacks. I just prefer to let the work drive the train rather than imagine that I’m writing this story for myself. It’s for the readers. Anything else is therapy. It’s selfish. Amateurish. Naturally, I enjoy the work. I love it. But I’m never in doubt that some stranger, some day, will render judgment, not my peers or the papers. Even at my most egotistical, such as being aware of one day being asked about it, I never allow myself to forget where the stage ends and where the first row of the audience begins.

I roamed the cemeteries, chip shops, the IRA monument in the town square and all the fields surrounding the town while hefting my old Contaflex camera. I always shoot tons of images, most of which I never use. I suppose you might say it’s what a location scout working on a movie might do. But it integrates well into my ritual of pounding the pavement, shutting up, building a runway for the characters before helping them take off.

Only at this point do I acknowledge my hungry dinner guests “inspiration” and “creativity.” They’re not the masters of anything, but equal partners, if I must give them a fair designation. They only showed up once I took a shovel and started digging. Jim, the Walsh sisters, their tragically enamored Aunt Moira and the town of Castletownbere became real because I enlisted myself in the army of one, dedicated only to self-forgetfulness and to beating out some meaning from my random observations.

In sum: Darling Jim became a book because I fell in love with the idea of picking up an aural shovel and never stopped listening to what I heard as I dug. I trust nothing but the act of writing at least five pages a day to yield something even I have no idea how to describe. It’s the gold dust in the river of mud. It’s not for me. It’s for you.

I suppose “inspiration” will find a clever way to take credit for that, somehow.

9 May 2009 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.