William Dietrich & the Early Modern Swashbuckler

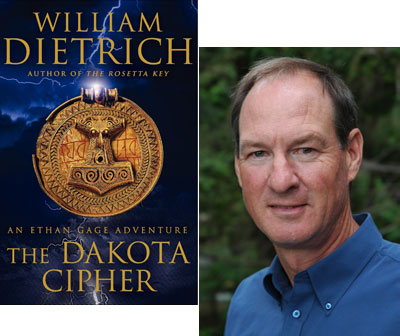

A few years back, I started reading a novel called Hadrian’s Wall by William Dietrich—I’d picked it on a whim, because it happened to come in the mail that day, and I wasn’t expecting much to start, but it turned out to be a genuinely compelling read; basically, Dietrich took the decline of the Roman Empire and bathed it in a 1950s noir atmosphere perfectly suited to the cultural decay and corruption. I was hooked by the end of the first chapter and pretty much read the thing straight through in just a day or two. Since then, Dietrich’s gone on to write a series of historical adventure-thrillers (the Hollywood pitch might go Flashman meets the Da Vinci Code) that has hit its third installment with the publication of The Dakota Cipher this week.

Napoleon’s Pyramids, the first book in the series, “was inspired by Bonaparte’s epic invasion of Egypt,” Dietrich recalled recently, introducing the essay that he’d written for Beatrice. “That episode was a clash of cultures between a European army and mysterious Muslim world, seen through the eyes of an American adventurer, Ethan Gage. The Dakota Cipher is also a time-machine trip through cultures, in which Ethan moves from the glittering chateaus of France to raw New York, a meeting with Thomas Jefferson in infant Washington, and then on to the frontier. There he brushes up against native American life and the frightening freedoms of the West.” My question: How did Dietrich hit upon this corner of history, and this hero?

In all my books I try to take my readers to a different world, be it Roman Britain, Antarctica, or the Holy Land in 1799. Ethan—a gambler, sharpshooter, treasure hunter, and romantic—is above all curious, and we see the dawn of our modern era through his wry perspective. I use humor and horror to give a rounded view of a period in which so many things began: The industrial and scientific revolutions, the conscription of whole populations in titanic wars, the birth of propaganda and the secret police, and Enlightenment ideas that inspired political change in the United States, France, and Britain.

My writing is inevitably influenced by my career as a newspaper journalist. Without quite planning to, I’ve found my heroes and heroines are usually observant adventurers thrust into new cultures and environments, which is a fair description of ambitious reporting. As a former environmental and science reporter, I also have a particular interest in how geography affects individuals and society. My books have vivid settings that characters react to.

Most important, I learned in the competitive world of journalism that if you don’t make it fun and interesting, it doesn’t get read. My novels are chock-full of love and war, treachery and triumph, twists and turns. Ethan has added a new dimension to my novels, because he has a self-deprecating sense of humor. He’s good company, which is why I keep writing books about him.

Even though Ethan Gage is a protégé of the late Benjamin Franklin and firmly fixed to his era, he is also quite intentionally a modern man. He seeks opportunity amid events in which he has little control, reflecting the relative powerlessness most of us feel in our very complex and crowded modern world. He’s both idealistic and skeptical. He is torn between his instincts for pleasure and his resolutions to reform—any dieter can recognize the problem—’and his relationships with women continue to evolve. (His tumultuous experiences in The Dakota Cipher help set the stage for momentous personal change in the fourth novel of the series, to be published in 2010.)

As an historical novelist, I’ve also set books in World War II and the late Roman Empire. So why the Napoleonic period? Bonaparte fascinates me as representing the best and worst of human nature. Typically portrayed as a villain by British authors and a hero by French ones, to an American he seems, well, American. He was an immigrant to France, from his native Corsica, and a self-made man who is idealistic, overbearing, earnest, and cynical. Like a Greek tragedy, his success carries the seeds of his destruction: he can’t stop making war. Napoleon contradicts himself a hundred times with his own quotations, and is both brilliant and blind. A writer could hardly ask for better material.

If ours is an age in which people strive for money and fame, Ethan’s era was a time of glory and romance. Uniforms were resplendent, dresses scandalous, schemes epic, ships magnificent, gossip malicious, attacks reckless, decoration lurid, art romantic, battlefields horrifying, espionage daring, morality confused, and ideas conflicting. Much of our planet was still unexplored. The passions of the period make great material for a novel.

My hope is that Ethan gives readers a different perspective on this period than they’ve ever encountered before—and that his propensity for getting into trouble will keep them turning pages late into the night!

24 March 2009 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.