Daniyal Mueenuddin Has “The Singers” Running Through His Head

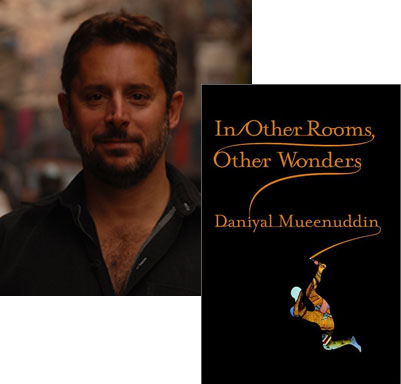

I had the pleasure of meeting Daniyal Mueenuddin a few months ago when he came to New York a few months ahead of the publication of In Other Rooms, Other Wonders, his debut collection of short stories, introducing himself to the literary media. I quickly became engrossed in his stories about life in the cities and villages of Pakistan—this is definitely one of the first great collections of 2009, and if I know the folks at The Story Prize, they should already be setting it aside for the shortlist from which they draw their shortlist. I invited Mueenuddin to tell readers about one of his favorite short stories; in a wonderful twist, he chose instead to focus on a Turgenev story that’s stuck in his head for slightly different reasons.

Turgenev is not the greatest of the Russian writers of prose fiction—Nabokov ranks him fourth, after Tolstoy, Gogol, and Chekhov—and “The Singers” is not my favorite short story. The ending, however, has always intrigued and troubled me, and often lodges in my mind when I’m considering the endings of my own stories.

Since I’m indulging in lists and rankings, I will suggest that, when writing short stories, the hardest part is the ending, then the beginning—and then, surprisingly—the title. Beginnings are to a degree given—there’s a reason that you’ve chosen to write this particular story, something you heard or an image or a situation—and so, as you sit facing the blank page, pencils sharpened, lights adjusted—you know more or less what direction you’re heading in. And then, journeys begin with light feet and a light heart, the wind at your back and no monsters yet encountered.

Titles are a special case—some people have a knack for them, like crossword puzzles or naming dogs. We all have our favorites: Blood Meridian, The Wide Sargasso Sea, etc., etc.

But endings! Endings are vexing. There you are, with all the long puffing train behind you, pushing you, the weight of the whole story pushing you forward, now as you reach your terminus—and yet, you must go off the rails, and going off the rails, you must keep the wagons behind you upright and must pull the whole thing up to the wrong station, the surprising station, the right station, but right in a way that neither you nor the reader expected, built of ice or rococo plaster, rainswept or haunted or full of bankers.

This is where Turgenev’s story comes in.

Like so many of the stories in A Sportsman’s Sketches, this one seems hardly constructed at all. A hunter, a small landowner, walks into a peasant tavern in a run-down village on a hot summer day. A highly miscellaneous group is assembled—the Blinkard, the Gabbler, the Wild Master—these are their nicknames, and they’re an odd lot, loungers and boozers, ‘road masters’ as we call them in Pakistan, men whose main occupation is strolling up and down the village street.

It turns out that there is a contest on, a singing contest, with the prize a pot of beer. The local champion, known only as “the booth-keeper from Zhizdry”, wins the draw and begins. He sings artfully, playing with his voice, “like a woodlark, twisting and turning it in incessant roulades and trills up and down the scale, continually returning to the highest notes, which he held and prolonged with special care.”

When he finishes, the louder part of the crowd by acclamation crowns him the winner, no contest—but cooler heads prevail and his rival, Yashka the Turk, an unknown traveler, is asked to try his voice. “The first sound of his voice was faint and unequal, and seemed not to come from his chest, but to be wafted from somewhere afar off, as though it had floated by chance into the room.” He continues, in a voice unlike anything the narrator has heard. “It was slightly hoarse, and not perfectly true; there was even something morbid about it at first; but it had genuine depth of passion, and youth and sweetness and a sort of fascinating, careless, pathetic melancholy. A spirit of truth and fire, a Russian spirit, was sounding and breathing in that voice, and it seemed to go straight to your heart, to go straight to all that was Russian in it.” When he finishes, the audience is silent, the innkeeper’s wife in tears—she withdraws into another room. The rival singer, the booth-keeper, goes up to Yashka. “‘You… yours… you’ve won,’ he articulated at last with an effort, and rushed out of the room.”

Now comes the shift, irrational and intuitive, that I find so intriguing. The narrator, the landowner, goes out of the inn, his world made strange by the music he has heard, falls asleep in a hay loft, and rises just as night has fallen. Collecting himself, he sets off home, passing the tavern, where all are now drunk and rolling around like beasts—he sees it through the window. Walking along the dark road, he hears a boy calling a name, Antropka, Antropka, over and over again. Finally Antropka answers, from a different direction and afar. “Wha-a-at?” he asks. “Come ho-o-o-me now,” cries the first voice. Silence, then again Antropka calls, “Why… ?” And the answer, “Because father wants to be-e-at you.”

And that’s the end of it—leaving the strange nutty taste of this ending, which is almost unsatisfying, lingering on our palates. What does it mean?

27 January 2009 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.