Tony O’Neill and the Novel of Existential Drug Addiction

“I’m not AA at all,” Tony O’Neill declared as our interview about his second novel, Down and Out on Murder Mile, got into full swing. “I still get high a lot. I still drink. I just don’t put needles in my arms. I’m as recovered as I want to be.” He isn’t particularly interested in being a spokesperson for the futility of the War on Drugs, but he has a particular loathing for the recovery culture’s insistence on forcing a mindset of weakness on addicts. “That was the thing that kept me going back to heroin when I was in AA,” he explained as we sat in the upstairs café of a downtown Manhattan bookstore. “Having a beer is not a relapse, and I realized that it was becoming a pattern from me when I was in the program; if you tell a junkie he’s relapsed, it gives him the perfect excuse to start doing the drugs he wants to be doing.”

Down and Out on Murder Mile draws freely upon O’Neill’s experiences when he was heavily using crack and heroin. The opening scene, in which the protagonist heads out into the night on Christmas Eve looking for a score, was based on real events, and was originally conceived as a self-contained story that simply kept growing. “Given what my life had been like up to the point when I started writing, it would have been crazy for me to ignore it,” he conceded. “I’ve probably stockpiled material for fifty more books if I didn’t get bored talking about myself… [But] I feel like you have to bring somethng else to the table.” For O’Neill, that means trying to recapture the 1990s Los Angeles drug subculture, a time and place he sees as largely vanished: “The corner where I used to score crack has a multimillion dollar condo on it now.”

18 November 2008 | interviews |

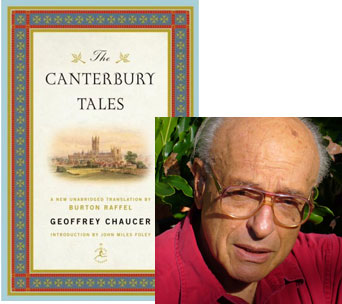

Burton Raffel’s Second Try at Translation: A Half-Century and Counting

It’s time to announce a new series of guest essays at Beatrice, one that I’ve been looking forward to launching for some time now: “In Translation” will give readers an opportunity to hear from the men and women who help bring a wider selection of international literature to English-language readers. Sometimes they’ll talk about their experiences working on a particular text, and sometimes—as in this essay by Burton Raffel, who has created a new version of Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales for the Modern Library—they’ll share broader reflections on the art of translation. Raffel, for instance, lets us in on the origins of his impulse to translate the great works of other languages, from early classics like Beowulf and Don Quixote to comparatively recent fare like The Red and the Black… and why he abandoned that goal the first time around. (And, luckily for us, what got him back in the game.)

I don’t think many translators think they were born to that trade. Most of the translators I know, or know anything about, have started in different directions and, at some indefinable point, have slid sideways and, much to their surprise, begun translating.

That’s both true of me and also false. I heard a lot of languages, in my parents’ house—Russian, Yiddish, Ukrainian, Hebrew, Polish, Spanish. But these were their languages, not mine. I was, I felt, 100 percent American. After all, I had been born here, and they had not.

But when I started to study French, at age ten or eleven, I fell head over heels in love with it. I talked French to myself, silently, as I walked to and from school. This was my language: I even liked its grammar, though I hated ordinary grammar lessons, parsing dull English sentences with stupid, meaningless labels. Lying in bed, in the dark, I talked French to myself. If God spoke a human tongue, I used to say, it would have to be French.

I studied both French and Spanish, in high school, adding German when I got to college. My introduction to French literature, as a university freshman, was epochal. I liked English poetry; a few years earlier I had belonged to a teenage Chinese poetry-writing club. But the sheer sound of French verse seemed to me like the voices of angels. “Il pleure dans mon coeur, comme il pleut sur la ville” (Verlaine)—or a three-word phrase in Baudelaire’s “Hymne à la beauté,” five syllables, not one of which could be sounded in English. My twelfth-grade French teacher, back in 1943-44, had been a Parisienne, stranded in New York because of World War II. She spoke to us only in French; she drilled us in reshaping our mouths to handle those stunning French sounds. I was incredibly lucky, though I’m not sure I then knew it.

I was writing reams of adolescent poetry in English, I was reading modern American poets, so in my freshman year I tried to translate some of that gorgeous French into my native language. The wonderful professor who introduced me to the great French poets of the 19th and 20th centuries would smile, pleasantly, and shake her head. She was right, I had no idea what I was doing, except that I knew my translations were not much good. I gave it up.

17 November 2008 | in translation |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.