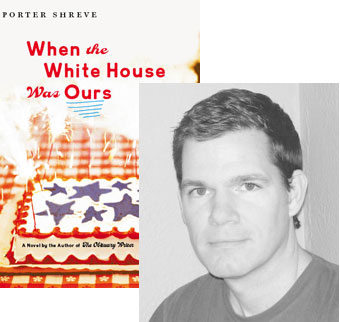

Porter Shreve Reclaims the White House (Our House, Too!)

I’m still in the opening chapters of Porter Shreve‘s new novel, When the White House Was Ours, but I’m totally loving it—even looking forward to subway rides where I know I can get in a solid chunk of reading time! In this essay, he explains how the novel is a mashup of his childhood experiences, with a whole lot of fictional twists added to make things even more interesting.

I was seven years old in 1973 when my parents received a grant to start an alternative school in Philadelphia. We lived in a cozy fieldstone cottage in Mount Airy, with my uncle Jeff and the remaining hippies from a small commune Jeff had formed in Colorado. My father, who had been the star of the University of Pennsylvania football team during its few promising years, was well liked around the city. But he couldn’t believe his good fortune when a near-stranger named Woodward, who owned many properties in North Philadelphia, handed him the keys to a vacant house a few blocks from ours, and said, as long as you’re starting a school, you’re going to need a schoolhouse. Rent-free for a year, renewable thereafter. With help from Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, my father named the school “Our House,” as in “Our House is a Very, Very, Very Fine House.” He advertised in the community papers, posted flyers around local schools, and by the end of summer nearly a hundred students had enrolled.

Some used “Our House” as an after-school program. The schools they went to didn’t offer classes in photography, painting and drawing, music or creative writing, or their high school courses hadn’t caught up with the social progress of the sixties. At “Our House” kids could study the arts, feminist literature, Indian myths and urban cultures. For others, the school provided an open community. Many evenings, guests would come—musicians, writers, activists, sociologists—and stand in front of the fireplace playing instruments or lecturing, taking questions from the students, who sat cross-legged on the floor or slouched on comfortable couches. One of the downstairs rooms served as a gallery space for student artists to share their work. The walls and tables were filled with pottery, wooden toys, candles and dream catchers, macramé, batiking, weaving, paintings, photographs and poetry chapbooks. My brother, sister and I never needed childcare—we had a school all our own.

I’d always wanted to write a book about “Our House,” and for years I assumed it would be a memoir. But when I sat down to recall my family’s ragtag experiment I could remember very little. I began to interview my parents and uncle, grill them for anecdotes, but it was fall 2004 and I kept getting distracted by the presidential campaign. My wife and I had just bought a house in Indiana—Bush country—and we had the acute anxiety of exiles about the election. I began writing a short story about a couple of liberals who find themselves awash in the garish glow of FOX News pulsing from their neighbors’ windows. Then, somewhere along the line, all that thinking about politics took me back to another time in my childhood—1976—when my family moved from Philadelphia, leaving the school behind, and settled in Washington, D.C., where my parents volunteered for Jimmy Carter.

From these two moments of idealism—the alternative school and Carter’s campaign for president—I realized I had the makings of a novel. As my memories intertwined the story took on a life of its own. I knew as a fiction writer that I needed to visit all kinds of trouble on this family; stories, after all, as Charles Baxter has said, are “hell-friendly.” So I moved everyone to D.C. into a crumbling mansion in a dodgy part of the city. I had them launch the school under their own roof, and I made the landlord a vindictive old college friend of the father’s. I made sure that the father had recently been fired from his job and that the mother was at the end of her rope. I appointed the hippies to the faculty, and made them disciples of Abbie Hoffman, then followed my characters through a series of challenges—poverty, marital strife, infidelity, theft, and false imprisonment—in the bleak economy of 1976 and 1977. I made the protagonist, in some ways a stand-in for myself, a thirteen-year-old kid obsessed with presidential history, determined to keep his family together, and smitten by the landlord’s beguiling daughter. And gradually I discovered this family’s collision with history: “Like Jimmy Carter’s presidency, our years in Washington began with hope then slid into crisis.” The book has just come out in the heat of another campaign season, this time a moment of hope in the midst of crisis. Will the White House be ours again? Oh, what I’d give for the idealists’ return.

6 October 2008 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.