Deborah Weisgall Finds Modern Resonance in George Eliot

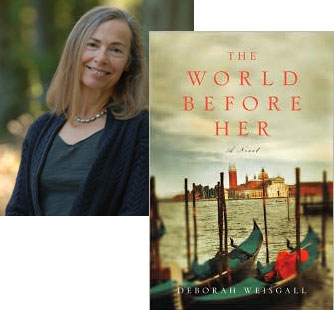

In The World Before Her, Deborah Weisgall contrasts the life of Marian Evans—known better to generations of readers as “George Eliot”—and a (fictional) contemporary sculptor, both of whom travel to Venice during moments where their personal and creative tensions have them at a crossroads. Why Eliot? Weisgall explains what she found in Eliot’s novels that spoke to her own literary concerns.

Of course I read George Eliot in high school. Tenth grade: Silas Marner, Adam Bede. The Mill on the Floss my senior year. These were harsh tales: passionate young women paid with their lives for their appetites—physical and emotional. Fates not so different from those that befell poor Emma Bovary or Anna Karenina. For a young and passionate woman trying to navigate the rapids of heart and mind, these stories were further examples of impossibility.

I was not wise enough to perceive that there was a difference—a difference of sympathy. George Eliot gave her women an ardor, an appetite, that went beyond the physical, a yearning that was emotional and intellectual—that struggled with moral issues as well as the strictures of society. It was not until I was a grownup that I understood how she was writing about love.

I did not read Middlemarch until I was married and had a daughter, until I had, at some cost, found a paddle and steered myself into relatively calm and happy waters. I began the novel out of duty—how could an educated person, one whose job in life was writing, not have read Middlemarch?—I finished it transformed, awash in possibility. Here was a novel that resonated—here was a story of a passionate woman who didn’t commit suicide or throw herself under a train. Here was a novelist who understood sex. More than sex: ardor—intellectual and physical, who had wrestled with it herself. Not only in personal terms, with questions of self-fulfillment, but in moral terms: how does this ardor affect the world? How does it translate beyond the self?

And there was something else. This was a writer, I sensed, who also understood love, who understood the richness of domestic bliss, the pleasures, physical and emotional, of partnership. A writer, moreover, for whom love was not the only thing that mattered, but for whom it was bedrock. Three-quarters of the way through the book, I was consumed with anxiety. I had to stop reading; I didn’t think that I could survive if Dorothea didn’t get her guy. So I skipped to the end, reassured myself, and kept going.

I did this despite understanding that Middlemarch is far more than a love story. It is a novel in which George Eliot conjures a world in flux, where the railroad had diminished distances, where factories and mines had displaced fields and meadows, where geological time was supplanting biblical time; a world, in its convulsive changes, not so different from our own. The issues her heroine faced were identical to those facing women of my generation: how to make room for love and meaningful work, how not to lose one’s self in marriage, how to live—in a moral sense—a good life.

So I finished Middlemarch and read Daniel Deronda, and read it again, and I began reading biographies of Eliot. I was struck, and deeply moved, by the discrepancies between her real life and the lives she gave her heroines. Marian Evans—George Eliot was her pen name—in real life had no children. She did not marry until she was sixty, though for twenty-five years she lived, very happily, with George Henry Lewes, a writer and critic and a married man whose wife was kept busy producing babies with her husband’s best friend. She called Lewes her husband; he was her partner in all things. She took his first name as her pseudonym, not because it was difficult for a woman to achieve success as a writer, but because she believed that without him she would not have been able to write fiction at all.

But though Eliot wrote heroines who were powerful and complicated women, she could not give them lives of their own. If in her books they had done what she had done—become writers and artists, lived with the love of their lives however irregular the situation—Eliot knew, from her own, bitter experience, that these characters, and their novels, would have been rejected and reviled.

Marian Evans’s real life was in many ways far more modern—and far more subversive—than the stories she could give her heroines. This was one of the reasons—if writing a novel can ever be entirely reasoned—that I wrote The World Before Her. From the beginning, I saw it as two stories: the first, about Marian Evans in the spring of 1880, beginning six weeks after her marriage to John Cross, a young and handsome man, and the second, a kind of retelling of both Middlemarch and Daniel Deronda, set a hundred years later. It is a means to bridge distance, to weave connections, to confirm George Eliot’s instinct for the necessity of love. In this age that dismisses romance, my modern heroine’s story, her understanding of the love’s richness, the peace of still waters, the rewards—and the price—of domestic bliss, is in its way subversive, too.

2 July 2008 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.