Author2Author: Carolyn Burke & Hazel Rowley

I first met Carolyn Burke several years ago, when I interviewed her about her biography of Mina Loy. Last year, she wrote Lee Miller, a biography of the acclaimed photographer that was nominated for a National Book Critics Circle award. She suggested to me a month ago that she’d love to chat with Hazel Rowley, who had just published Tête-A-Tête: Simone de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre, about some of the issues surrounding literary biography. I thought it was a great idea, and here we are…

Carolyn Burke: I’m interested that rather than writing a conventional biography, you chose to write about Sartre and Beauvoir’s relationship. How did you decide on this approach? What were the consquences for the way you shaped the narrative? What sorts of things did you choose to emphasize, to omit?

Carolyn Burke: I’m interested that rather than writing a conventional biography, you chose to write about Sartre and Beauvoir’s relationship. How did you decide on this approach? What were the consquences for the way you shaped the narrative? What sorts of things did you choose to emphasize, to omit?

Hazel Rowley: I was keen to move away from womb-to-tomb biography, and to feel freer as a storyteller. And I did feel freer. I have never enjoyed writing a book more. Obviously I still had to get the facts right, but I didn’t have to take on board their whole lives (the narrative begins in the summer of 1929, when Sartre and Beauvoir met, and it pretty much ends with Sartre’s death in 1980). I talk about their writing lives and their iconic roles as public intellectuals (intellectuels engagés) because these were important aspects of their relationship, but I didn’t feel obliged to fill out the picture. What a liberation! After my other books, I felt as if I were wearing dancing shoes.

I tried to give equal space to Sartre and Beauvoir. It’s true that most readers sense that my sympathy lies with Beauvoir, but I admire both of them in many ways. Sartre’s insecurities made me feel a real tenderness towards him. He drank a lot; he took enormous quantities of speed; at times he was on the verge of madness. It’s my belief—contrary to public opinion—hat he needed Simone de Beauvoir more than she needed him.

What did I choose to emphasize or omit? As philosophers and as writers, Sartre and Beauvoir adamantly believed they should tell the truth. I was guided by the same principle in my book. I wanted to tell the truth about their relationship and not to whitewash their behavior, but the fact is, their love life does not always show them in their best light, and I was conscious of the danger of trivializing these two 20th-century icons. In order to tell this story without simply muckraking, I took pains to sketch in the broader picture—to give a sense of their intellectual trajectory and their writing.

At the same time, I was determined to keep the book fairly short. I had loads of material. I was dealing with not one but two people, and this love story contains many other characters as well. The danger was clear. I could easily produce summary rather than story. The answer, I realized, was selectivity; I had to trim my narrative with a sharp razor. What to choose? Well, you tell stories that are revealing. Above all, you tell a good story!

18 June 2006 | author2author |

Author2Author: Jeff Chang & Simon Reynolds

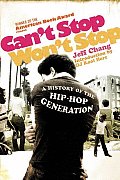

I’m always looking for great pairs to throw together for an Author2Author discussion, and I think this chat between Jeff Chang and Simon Reynolds is going to be a real winner. Jeff’s Can’t Stop Won’t Stop: A History of the Hip-Hop Generation and Simon’s Rip It Up and Start Again: Postpunk 1978-1984 tackle the formative musical years of my generation from two different directions, and it’s interesting to see how their work informs and relates to each other.

Jeff Chang: First off, congratulations on Rip It Up! It’s fantastic work, and more than deserves every accolade that’s come down. My formative music years also coincided with the turn of the ’80s and Reagan/Thatcher, and—all VH1 kitsch aside—I agree that it’s a period that has been easier to parody than take seriously. I love the breadth of the groups you cover in the book, from Adam and the Ants to PiL to the Slits; it resonates with my own musical explorations during my teens. I remember that reggae, Hawaiian music, and hip-hop were the sounds that I searched out, and that post-punk and new wave was what I was primarily reading about, in magazines like Rolling Stone, Musician, Trouser Press, and the occasional NME and Melody Maker that made it to my shores in the Pacific.

Jeff Chang: First off, congratulations on Rip It Up! It’s fantastic work, and more than deserves every accolade that’s come down. My formative music years also coincided with the turn of the ’80s and Reagan/Thatcher, and—all VH1 kitsch aside—I agree that it’s a period that has been easier to parody than take seriously. I love the breadth of the groups you cover in the book, from Adam and the Ants to PiL to the Slits; it resonates with my own musical explorations during my teens. I remember that reggae, Hawaiian music, and hip-hop were the sounds that I searched out, and that post-punk and new wave was what I was primarily reading about, in magazines like Rolling Stone, Musician, Trouser Press, and the occasional NME and Melody Maker that made it to my shores in the Pacific.

How in the world do you begin to capture this all under one big “post-punk” umbrella? And do you think it’s possible that the diversity of that period sets us up for the proliferation of micro-pop genres and niches these days? And how do you think the profusion of styles you encountered in your teens informed your views of music and culture?

Simon Reynolds: Thanks, Jeff, and big up ya chest for Can’t Stop, Won’t Stop, a colossal achievement—literally colossal (more on that later!). I did tons of research for Rip It Up but I can’t imagine what it was like for you embarking on a project that cuts across three decades of not just musical but social and political history. Perhaps you could talk a bit about how you approached such a huge undertaking, how long it took to research, and also the difficulty of deciding what to leave out.

On the subject of postpunk as umbrella term, the way I loosely defined postpunk was music that had been catalysed by punk but didn’t sound like punk rock in the classic sense of Pistols/Clash/Ramones. Bands that wouldn’t have existed without the spur of punk giving them the confidence to do it themselves, but who felt the true spirit of punk was not to repeat but to experiment and keep moving. The big exception to “catalysed by punk”—which requires a second-level definition of postpunk—is bands who happened to be in existence before punk happened; e.g. Devo, Cabaret Voltaire, Pere Ubu, the Residents. Some of them had been around many years, but only found a substantial audience because punk opened things up. That opening-up had several levels. Firstly, punk created an audience with an appetite for more challenging music. It shook up the major labels, and made them more likely to sign edgy bands or take risks—the chase to sign Devo as “the next Sex Pistols” is one example—for fear of getting left behind. Punk also catalysed the independent label movement, which provided a distribution network for weirdo music that would otherwise have just subsisted on a home-taping/mail-order level, and also a cultural context in which risk-taking music “signified” and found a proper reception. So overall, I’d define postpunk not as a genre of music but rather as a possibility space in which a host of new genres and scenes formed.

That open-endedness naturally lent itself towards diversity and fragmentation. So as the postpunk era proceeds, by the time we get near the end of the period I’m covering (1983-84) the distance between things is starting to get vast. There’s a gulf between Goth and the glossy New Pop stuff, between synthpop and the return-to-guitars of those bands I’ve dubbed “glory boys” (Echo & the Bunnymen, U2, etc). Everything is scattering and following its own divergent and often antithetical path. But the point of origin—the mythic site of lost unity—is punk. That’s the ignition point, the Big Bang. Even Duran Duran, who seem like the ultimate “like punk never happened” band, had started out wanting to combine Sex Pistols’ “God Save the Queen” and Chic’s “Le Freak.”

I don’t know if postpunk is the beginning of the modern age of genre fragmentation, though, because the early Seventies was like that, in a way: a diverse but diffuse era that people still have some difficulty getting a grip on. It’s more like rock history has alternated between periods of unity (the mid-to-late Sixties; punk; to a lesser extent grunge and early rave) and phases when consensus disintegrates and the tribes scatter. These periods of drift and diaspora tend to get seen unfairly as troughs or wastelands, which was one reason it was enticing (but also challenging) to attempt to write about the punk “aftermath” as both a unified epoch and a surge-phase.

15 June 2006 | author2author |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.