Author2Author: Jeff Chang & Simon Reynolds

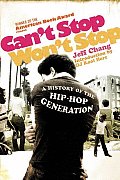

I’m always looking for great pairs to throw together for an Author2Author discussion, and I think this chat between Jeff Chang and Simon Reynolds is going to be a real winner. Jeff’s Can’t Stop Won’t Stop: A History of the Hip-Hop Generation and Simon’s Rip It Up and Start Again: Postpunk 1978-1984 tackle the formative musical years of my generation from two different directions, and it’s interesting to see how their work informs and relates to each other.

Jeff Chang: First off, congratulations on Rip It Up! It’s fantastic work, and more than deserves every accolade that’s come down. My formative music years also coincided with the turn of the ’80s and Reagan/Thatcher, and—all VH1 kitsch aside—I agree that it’s a period that has been easier to parody than take seriously. I love the breadth of the groups you cover in the book, from Adam and the Ants to PiL to the Slits; it resonates with my own musical explorations during my teens. I remember that reggae, Hawaiian music, and hip-hop were the sounds that I searched out, and that post-punk and new wave was what I was primarily reading about, in magazines like Rolling Stone, Musician, Trouser Press, and the occasional NME and Melody Maker that made it to my shores in the Pacific.

Jeff Chang: First off, congratulations on Rip It Up! It’s fantastic work, and more than deserves every accolade that’s come down. My formative music years also coincided with the turn of the ’80s and Reagan/Thatcher, and—all VH1 kitsch aside—I agree that it’s a period that has been easier to parody than take seriously. I love the breadth of the groups you cover in the book, from Adam and the Ants to PiL to the Slits; it resonates with my own musical explorations during my teens. I remember that reggae, Hawaiian music, and hip-hop were the sounds that I searched out, and that post-punk and new wave was what I was primarily reading about, in magazines like Rolling Stone, Musician, Trouser Press, and the occasional NME and Melody Maker that made it to my shores in the Pacific.

How in the world do you begin to capture this all under one big “post-punk” umbrella? And do you think it’s possible that the diversity of that period sets us up for the proliferation of micro-pop genres and niches these days? And how do you think the profusion of styles you encountered in your teens informed your views of music and culture?

Simon Reynolds: Thanks, Jeff, and big up ya chest for Can’t Stop, Won’t Stop, a colossal achievement—literally colossal (more on that later!). I did tons of research for Rip It Up but I can’t imagine what it was like for you embarking on a project that cuts across three decades of not just musical but social and political history. Perhaps you could talk a bit about how you approached such a huge undertaking, how long it took to research, and also the difficulty of deciding what to leave out.

On the subject of postpunk as umbrella term, the way I loosely defined postpunk was music that had been catalysed by punk but didn’t sound like punk rock in the classic sense of Pistols/Clash/Ramones. Bands that wouldn’t have existed without the spur of punk giving them the confidence to do it themselves, but who felt the true spirit of punk was not to repeat but to experiment and keep moving. The big exception to “catalysed by punk”—which requires a second-level definition of postpunk—is bands who happened to be in existence before punk happened; e.g. Devo, Cabaret Voltaire, Pere Ubu, the Residents. Some of them had been around many years, but only found a substantial audience because punk opened things up. That opening-up had several levels. Firstly, punk created an audience with an appetite for more challenging music. It shook up the major labels, and made them more likely to sign edgy bands or take risks—the chase to sign Devo as “the next Sex Pistols” is one example—for fear of getting left behind. Punk also catalysed the independent label movement, which provided a distribution network for weirdo music that would otherwise have just subsisted on a home-taping/mail-order level, and also a cultural context in which risk-taking music “signified” and found a proper reception. So overall, I’d define postpunk not as a genre of music but rather as a possibility space in which a host of new genres and scenes formed.

That open-endedness naturally lent itself towards diversity and fragmentation. So as the postpunk era proceeds, by the time we get near the end of the period I’m covering (1983-84) the distance between things is starting to get vast. There’s a gulf between Goth and the glossy New Pop stuff, between synthpop and the return-to-guitars of those bands I’ve dubbed “glory boys” (Echo & the Bunnymen, U2, etc). Everything is scattering and following its own divergent and often antithetical path. But the point of origin—the mythic site of lost unity—is punk. That’s the ignition point, the Big Bang. Even Duran Duran, who seem like the ultimate “like punk never happened” band, had started out wanting to combine Sex Pistols’ “God Save the Queen” and Chic’s “Le Freak.”

I don’t know if postpunk is the beginning of the modern age of genre fragmentation, though, because the early Seventies was like that, in a way: a diverse but diffuse era that people still have some difficulty getting a grip on. It’s more like rock history has alternated between periods of unity (the mid-to-late Sixties; punk; to a lesser extent grunge and early rave) and phases when consensus disintegrates and the tribes scatter. These periods of drift and diaspora tend to get seen unfairly as troughs or wastelands, which was one reason it was enticing (but also challenging) to attempt to write about the punk “aftermath” as both a unified epoch and a surge-phase.

I’ve loads of things I want to ask you about. Let me start by bringing up the weighty nature of our books—the sheer heft of them, physically. The Wire reviewer Rob Young described the UK edition of Rip It Up, which is longer and on heavier paper stock, as resembling a brick, something you could read and then throw through a megastore window as a protest against modern music! Your book’s even more hefty—it’soccasionally made me think of a small gravestone. There is something of a sense of summation, if not quite requiem, about both: what one might call two major “discourses of emancipation” which have arguably run their course. There have been many great (musically, artistically) rock records made since 1984, but I do think of postpunk as the last great spasm of the idea of rock as a force of change—at least in the mainstream (music + radicalism survives as a niche market).

The same thing has happened with hip hop: The idea of rap as a force of resistance, as black folks’ CNN, has been largely displaced (in the mainstream) by rap as entertainment, or as career structure for self-advancement on the individual rather than collective level. Neither genre is exhausted in musical terms, but it scarcely seems to be viable to think of them as “movements” anymore. And there’s a melancholy intimation, from the standpoint of today’s cynical realism, that such an expectation of music as a force for change was always too idealistic, an over-estimation. The idea that a song could actually fight the power… it can seem hopelessly naïve, especially when you see how devious and entrenched the people and forces who run Babylon actually are. Anyway I wondered what your feelings were on this topic, whether the kind of thing you’re celebrating in Can’t Stop, Won’t Stop—really from the title on down—is now “over”. To adapt the words of Monty Python’s parrot sketch, is “it” dead, or just resting?

Jeff Chang: Something that I’ve been thinking a lot about: I wonder if change always necessitates forgetting everything that just happened—in other words, if we always need to rip it up and start again? Your point about the diversity of music in the ’70s makes me realize that the punk and post-punk mythos was built on discursively narrowing the field of its opposition—not so different from how the hip-hoppers of the ’80s used disco, even though most rap before 1982 really was disco-based.

But the point seems to be that post-punk and (perhaps) hip-hop from say 1982 through 1997 are more continuous from these periods of breaks & big bangs than the discourse always indicates. The other thing you’ve given me a handle on with respect to hip-hop history is the idea of consensus giving way to drift and diaspora. Since 1997, we’ve clearly been in the latter period. In a theoretical sense, I do think a “movement”—and the engine of that, a desire for change—is possible without a center. But there is no unity now. I feel like the new consensus may not come from within U.S. borders, but I also recognize lots of folks think I’m crazy.

The question about leaving stuff out. You noticed I’m sure, and many others did, that I slipped past 1996-1997 in Can’t Stop Won’t Stop. Honestly, I felt lost in 1997: Pac and Biggie were dead, SoleSides had ended, the wave of media consolidation was in full swing (although it wasn’t clear at the time), and the underground (such as it was) was taking all kinds of sucker-punches—business-wise with distributors shutting down and major labels really beginning to narrow their focus, and aesthetically with the bling-and-champagne turn. I turned back to writing, but I ended up including very little of it in the latter part of the book.

On to gravestones! (LOL.) On the “hip-hop is dead this time, isn’t it?” question: Shortly after the publication of the book, I was pointed to an essay by someone much younger describing the arrival of his “post-hip-hop generation,” a partial repudiation of the hip-hop gen, blaming us for rampant minstrelsy, misogyny and materialism, among other things. I certainly feel like a gap has opened up between those of us who experienced the ’80s (and the ’90s) and those born during the decade. I think I’m in the distinct minority among my peers as one still thrilled by the rise of local scenes: hyphy, grime, snap, etc. I worry that my peers are beginning to sound like the elders sounded when we stepped onto the world stage in the late ’80s. And, per the great activist Richie Perez’s quote, I accept that the act of summing up a generation possibly means its time has passed, even as I hold out hope we can still get it right. It’s all very contradictory.

There’s a big part of me that wants to respect that young people have to find their own way, that doesn’t want to shit on the young’ns thing by droning on about how good it was back in the day. And I think it’s too easy to be bored or saddened or angered by all the noise in mainstream pop culture…and there’s just so much more noise now than when we were growing up. But I think disempowerment, or maybe to use a more aesthetic word, a lack of agency doesn’t necessarily follow. Isn’t this why we searched for those strange sounds when we were young, the sound of the counterculture?

I worry that my peers are overly cynical about young people enslaving themselves in the pop-culture matrix, too quick prone to make sweeping generalizations about the “them” on the other side of an age gap they don’t yet recognize, while carefully working to burnish their own story. I’ve straddled that line. Can’t Stop Won’t Stop was explicitly conceived as a way to burn through all the baby-boomer platitudes with a little myth of our own. I tried to be as real as I thought I could be, but in the end, I couldn’t escape writing what a good friend of mine called a “heroic narrative”. Critical historiography be damned. At the same time, I’m busy trying to collect all the flowers of change I see, perhaps even before they’ve bloomed. Against time and my peers, I remain optimistic about hip-hop, even as I recognize it may be in the process of becoming the next thing.

My politics have always shaped my aesthetics, probably to a fault. One thing that has always made your writing “must-read” for me is that you always seem to inhabit the aesthetic you are writing about. Your voice has changed as you’ve moved from one genre to another. Rip It Up reads much differently from Generation Ecstasy reads very different from The Sex Revolts, and so on. From a reader’s point of view, it’s always a challenging and satisfying journey.

My politics have always shaped my aesthetics, probably to a fault. One thing that has always made your writing “must-read” for me is that you always seem to inhabit the aesthetic you are writing about. Your voice has changed as you’ve moved from one genre to another. Rip It Up reads much differently from Generation Ecstasy reads very different from The Sex Revolts, and so on. From a reader’s point of view, it’s always a challenging and satisfying journey.

Is this a conscious shift that you make when you move to a new subject? More to the point, I guess, do you have an interest in trying to mix these up, throw them all together, connect the dots and develop, say, an idea about how postpunk, grunge, rave, electronic musics, post-modern pop, hip-hop, how they all fit together? Do you at all work toward a unified theory of popular music? Or is this a project that is a uniquely American, rockist, modernist, neo-Marxist, whatever kind of notion?

Simon Reynolds: It’s not really a “conscious shift,” the differences of style and approach with each book; probably it’s more that the material dictates the style. (The Sex Revolts actually has three styles that unconsciously mirror the material: the first section, on misogyny and masculinism in rock, is argumentatively thrusting, relentless, slightly deranged; the middle part, on psychedelia and the androgynous “soft male”, is drifting and associational, c.f. Toop’s Ocean of Sound; the third bit, examining the various strategies taken by female artists, is fractured and detail-oriented.) But with Rip It Up I did arrive at an approach, partly consciously and partly just through how things worked out, where I wasn’t really concerned with imposing my own take on everything, but more endeavoring to understand what the protagonists were trying to do, where their heads were at. I saw my goal as being to illuminate the artists’ musical and intellectual adventures by delineating the context they operated in.

I was conscious of the fact that postpunk was densely populated with incredibly smart and articulate people who had a strongly defined sense of what they were doing, and this made the job different from writing about, say, electronic music, which was much more of a blank canvas for critical projection. With postpunk, the groups get critiqued and occasionally rebuked, but the general spirit of the enterprise was supportive: as I said before, these people, for all their flaws and, often, their ultimate failure, are heroes to me.

“A unified theory of popular music”… One part of me feels a really strong pull towards doing this, but I also know this is most likely a foolish and foredoomed project. Even if I could come up with an over-arching theory that “explained” the main things I’ve written about over the years–postpunk, neo-psychedelic rock, rap, rave–there’s so many other kinds of music that I enjoy and that have a powerful effect on me that I’ve never been able to account for adequately with whatever Master Theory I’ve been touting at any given moment. For instance, this weekend I’ve been playing Fleetwood Mac nonstop. You could make a case for Lindsey Buckingham as an auteur-producer visionary (apparently he was listening to dub when he produced Tusk) but otherwise it’d be hard to say what the Mac’s music has in common with postpunk/psychedelia/rave/et al. Yet it slays me. I once wrote a piece on Tusk that started with me as a postpunk fan in 1980 being ambushed by “Sara” on the radio, how it was an “aberration” in taste otherwise constituted by PiL/Gang of Four/Joy Division. In some ways, though, such aberrations are the most interesting things of all.

I liked what you said about wanting to “burn through the baby-boomer platitudes with a little myth of our own”. You wrote something along those lines in the introduction to Can’t Stop, right? I recognized an affinity there with Rip It Up—the same frustration and fatigue with the endlessly retold tales of the Sixties, the desire to big up one’s own era. That’s something I made explicit in my own introduction, (over)stating the case for the postpunk era as a fair match for the 1963-67 period both musically, and in terms of a spirit of change and political turbulence infusing the music. There’s definitely a sense of generational jousting there, even though I love the music of the Sixties and in some ways feel like a child of the Sixties (born in 1963).

How one goes about celebrating one’s own formative era without bumming out the youth of today is a tricky thing to pull off, of course. I certainly wasn’t claiming that postpunk was the last time rock mattered or had power (in my own lifetime as critic a/k/a “professional fan,” there’s been hip hop, rave, grunge, and many other things less obviously momentous; apart from a couple of pronounced lull years, I’ve never lacked for something to get worked up about in print). But there was a unique combination of historical circumstances that made that moment (the six or seven years after punk) exceptionally exciting and productive. A “heroic narrative” is definitely what I had in mind; although a lot of the individual narratives of bands and labels end in ignominy of one sort or another, these characters did seem heroic for the way they tried to do something different, something difficult. Time and again, they took the path of most resistance.

Your guarded optimism about hip hop’s future is admirable (I want to come back to this at some point, the question of being a “hip hop patriot”, which, although I love the music and find it endlessly fascinating and thought-provoking, I’ve never quite been, for a bunch of reasons). One thing I noticed about our books is that, as much as they cover a lot of artists, they both have a pivotal band, a group that gets two chapters. Intriguingly, both groups start with the word Public: Public Enemy and Public Image Ltd. If, as Simon Frith once wrote, punk is all about public gestures—semiotic terrorism, the use of publicity and hype as the basic material of artistic expression, a theatre of provocation and controversy—then Public Enemy were true punks. That’s how they got written about at the time, as I recall, at least in the UK: the Black Clash. (I wrote about them and Def Jam at the time as “black rock”, which I think they were much more interestingly than, say, Living Colour were). “Rebel Without A Pause,” you could almost see as their “White Riot”: The stance and the sound of it is saying “black punk, black punk, we want a punk of our own”! Didn’t the Bomb Squad deploy mid-frequency sounds, the same ones that distorted electric guitars transmit, to give PE’s records a punk-like attack?

Public Image Ltd were actually doing something completely opposite: PiL was Lydon’s retreat from the arena of public gestures. It was John Lydon dismantling his Johnny Rotten persona in order to escape the Public Enemy #1 status that had put him in the cross-hairs of patriotic rage, a target for royalist retribution during 1977’s summer of “God Save the Queen” . Shucking off the burden of being simultaneously rock savior and media anti-Christ, PiL was Lydon unveiling the “real me” and embarking on an emotionally expressionistic art trip. So in a sense Public Enemy and PiL were going in reverse directions.

There’s a couple of ways that Public Enemy remind me of postpunk, though. One is the idea that it’s no use having radical content if it just sits on top of unadventurous or tame-sounding music; the music has to be as challenging and confrontational as the lyrics. The other is the whole concept of “edutainment,” the didacticism that crept into rap in the wake of PE (I recall a mini-trend for videos with blackboards and lecterns!). The whole idea of being “conscious” is totally in tune with the postpunk era: being aware as being awake, not being lulled into a trance by consumerism or propaganda, constantly being in a red alert state of ideological vigilance. And you write in Can’t Stop, the immediate precursor to PE was a phase in rap where people talked about getting stupid, getting dumb: concussive bass, retarded tempos. The whole feel of PE—the fast tempos, the paranoid thinking—reminds me a bit of the amphetamania that runs through the whole postpunk era, common to everyone from PiL to Scritti Politti to The Fall.

Jeff Chang: There’s a quote by Anne Magnuson at the end of your chapter on New York’s mutant disco and punk funk that talks about decentering the “Bright Lights, Big City” narrative of cocaine-snorting stockbrokers to people “who had to create art, or die.” It seems to me that class aspiration is a recurrent theme in the book, from the late 70s art-school lean toward Marxist and anti-racist solidarity politics for authenticity (a stance I certainly recognize in the US context) to the “Penthouse and Pavement” critique of ambition and aspiration embedded in the New Pop (that is startlingly reversed in the course of months, and finds an ironic denouement when folks like Martin Fry return to Sheffield). I’ve been thinking about this a lot within the context of hip-hop’s ongoing crisis, its apparent dead-end in a materialist realism. Perhaps I should explain, and perhaps this will help contextualize some of the conversation that we have been having.

Everywhere I go in speaking with people and audiences about hip-hop, the dominant key is a mix of pessimism and nostalgia. The pessimism is over hip-hop’s apparent inability to sound the anger in the country over all that’s happening—a point that you strike in a very helpful, nuanced way in your own concluding chapter in relation to the postpunk revival (should we call it neopostpunk?)—and the nostalgia is of course for the music of the late 80s and early 90s that presumably was much more “of the moment” in its resistance. I find myself enunciating a strange, sometimes uncomfortable balance of affirmation and optimism. I link what I call the narrowing of content to media consolidation, and people are genuinely surprised to find out about what has happened to outlets like radio and video over the last decade. I remind folks that hip-hop is no more misogynistic or violent or homophobic than the rest of mainstream pop culture, although it often bears the burden of an allegedly progressive critique.

And I point people to the hopeful signs: the thriving of regional scenes in the South and the West despite vertical monopolies, the urgent hip-hop activist movement, even the largely unsung, in some ways surprising, work of remarkable artists like Juvenile and David Banner.

One of the things I loved about your book was the way you described the dialogue between the artists and the British music press, a relationship so much dynamic than what we have here. In the brilliant chapters on New Pop, in particular, I was struck by the way you described the construction of New Pop in the music press–as you described it, the relief at being able to jettison guilt and despair and hypermasculinity for “paeans to consumption and polished product” (wonderful writing, natch). You follow that through ABC, Heaven 17 and Human League’s readjustment in the wake of their success, their failed attempts to become topical as they return home to confront Thatcher, heroin, and unemployment. Here US critics pick up the story, and valorize a return of roots rock—and in some senses, sadly, a restoration of the same-old-shitty-story when it comes to American nationalism, and gender, sexuality, and race.

15 June 2006 | author2author |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.