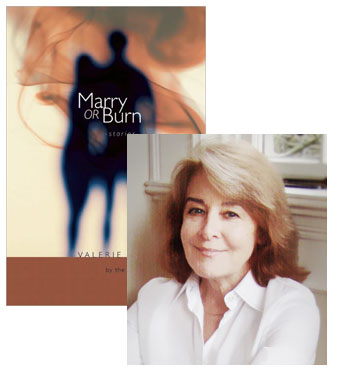

Valerie Trueblood & Welty’s Golden Apples

Valerie Trueblood is an expert at packing a short story with a rich backstory—the opening selections in her new collection, Marry or Burn, span years in their telling, and even stories like “Luck” or “Tom Thumb Wedding” that have a short time span on their surface contain dense pasts that weigh upon the unfolding present. But she doesn’t use the past to explain the present according to some obvious symbolic framework: It’s just that both are filled with incidents that offer implicit insights into her characters. In this essay, Trueblood tells us about another powerful example of the “show, don’t tell” principle of short story writing.

I have several editions of Eudora Welty’s story cycle The Golden Apples, the dearest to me a yellowed paperback, the one with the Bascove cover, small enough to be held open in one hand with the thumb on one half and the little finger on the other. Inside this small book is a world so dense, airy, lilting, lamenting, shocking, calming, and almost crazy with the sheer force of life that I can’t think of another book anything like it. Seven unruly stories are twisted up together, blown full of a sweet hilarity (“Whenever she opened the cabinet, the smell of new sheet music came out swift as an imprisoned spirit, like a pet coon”), and saturated with grief.

I wonder if Wallace Stevens read Welty’s stories. “Description,” he wrote, “is revelation.” I believe it’s in the short story—even more than in the poem—that we see what he meant.

“Why” is the territory of the novel, and the short story doesn’t dawdle there. It has left the path of reason and the outcomes dear to reason, and gone over into the land of the “what.” There, there’s absolutely no end to the things that can be seen to influence each other and to figure in someone’s fate. The short story is the place where these things get their due. My first awareness that they could be lifted into glory by a writer’s certainty that they were glorious came when I read The Golden Apples.

We’re going through a cultural impatience with the short story right now, while oddly engaged in shortening every text except fiction. But the story cycle has a bigger footprint; it is getting some welcome. A curious thing about the story cycle, or the novel-in-stories, or the modular novel, or whatever we decide to call it—and maybe a marker of the form—is that it doesn’t actually turn out to be a novel at all, no matter how often that well-meaning claim is made. The parts are greater than the whole. When you finish The Golden Apples you haven’t read a novel about the invented town of Morgana, Mississippi, but something else entirely.

I haven’t said what the stories in The Golden Apples are about, and to me, as a short story writer, it almost doesn’t matter. The word “about” is too small for these stories.

“June Recital” is the longest and most passionate. The piano teacher Miss Eckhart is the character with whom Welty said she found herself “oddly in touch.” Out of an utterly wrecked life looks Miss Eckhart, a foreigner in a southern town, “punctual…formidable,” “tireless as a spider.” Temporarily—since in these ballads of drowning, suicide, fire, madness and rape, nobody really escapes—she has been saved by music. Like that of the others who enact or endure their own stories in The Golden Apples, Miss Eckhart’s fate is briefly held at bay. She has a breakdown at the burial of the man she loves, she gets up, she goes on teaching piano to the dwindling group of children allowed to come near her as she descends in the social order. In a scene as passionate as the scene at the grave she watches her student prodigy Virgie playing the piano. The whole story—the whole book—is filled with an enchanted watching. Some of the characters are watching for something as well, and the failure of the thing longed for to arrive, or arrive in time, is what gives the stories their atmosphere of mourning, despite their eventfulness and earthy comedy and lack of complaint.

“What animates and possesses me,” Welty wrote, “is what drives Miss Eckhart, the love of her art and the love of giving it, and the desire to give it until there is no more left.”

The last sentence of her Washington Post obituary, given a paragraph to itself, is “Miss Welty never married.”

How much of life takes place in the walled kingdom of marriage, and where else can we find, alongside a willingness to be civil and accept the requirement of it, such a canny, ferocious denunciation of it? How reliably marriage, comical or pitiful, firms and upholds most of the females in these stories, but how clear it is that Welty’s favorites, Miss Eckhart and her beloved Virgie Rainey, are outside the walls, and dealing alone with aspects of life more dire and more joyful than the others are permitted. This is what Welty claims for the short story: the dire, joyful life, so wrapped in details we hardly know until we finish reading that what Virgie watched for was being offered to us, by the story. Description is revelation. Welty did this sixty years ago and the stories are still new.

28 January 2011 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.