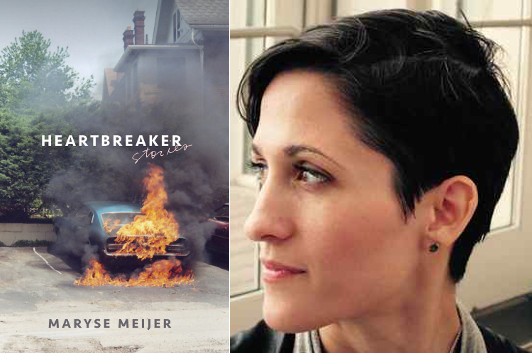

Strange Angels of Maryse Meijer’s Youth

photo: Danielle Meijer

Maryse Meijer has an amazing gift for writing about erotic fixation; see the title story in her debut collection, Heartbreaker, for starters. Even stories that aren’t specifically about erotic fixation, like “Shop Lady,” have an unsettling obsessive edge to them. And then there’s stories like “The Fire” and “Fugue” that veer into territory so unnerving they start to feel unreal—not unrealistic, let’s be clear about that, but unreal, or uncanny if you prefer. If the characters and worlds she creates start to remind you of modern horror fiction, well, as Meijer explains in this guest essay, that’s no accident.

I, like most children, grew up with a nose for the forbidden. I read romance novels (the more explicit the better) during math class in the fifth grade, giggled over The Satanic Bible with my twin sister, wrote love poetry about Jeffrey Dahmer, plundered the local video store for the goriest, tackiest B horror movies. I wanted to be shocked and to prove to myself that I was unshockable, and in the 1990s, before the internet was a given, you had to do a little digging to get to the good stuff.

For me, that meant stalking the book section of the local Tower Records, the only source of “alternative” reading material; I pored over anthologies of crime scene photographs, Robert Crumb’s racier comics, pocket-sized ‘zines with titles like Murder Can Be Fun. Only the Penthouses and Playboys were off limits, wrapped in cellophane and displayed out of arm’s reach; everything else, including plenty of explicit material, was easily accessible. No “adults only” section, no eagle-eyed employees monitoring the reading habits of a ten-year-old with her nose planted deep in an essay about Bob Flanagan’s erotic escapades in a hardware store. Heaven.

It was in the horror section of Tower Records that my life as a writer got its first big kick in the ass. I was probably looking for Anne Rice when a glossy black trade paperback caught my eye, its spine dripping with spiky red letters: Strange Angels. By someone named Kathe Koja. Some books speak to you from the shelf, by whatever mysterious magic of title/cover art/aura; this one grabbed me by the neck. I opened it up and started reading, sitting on a step stool, Smashing Pumpkins pumping through the store speakers. Here, finally, was the book I’d been looking for, the book that I hoped was out there, the book that I wanted other books to be, told in an edgy, stream-of-consciousness voice that shot me dead.

The story—a broke photographer stuck in some circle of blue-collar hell becomes obsessed with the mysterious drawings of a schizophrenic boy—had me sobbing by the end, hand over my mouth. My twin had the same experience. There wasn’t much in the book that reflected any of my own experience; I didn’t read to find out about myself. I wanted books that would take me somewhere, that would show me things I didn’t know, that would give me new worlds to disappear in. Books that would reveal secrets.

Strange Angels did that, and so did Koja’s other novels: Skin, The Cipher, Bad Brains, Kink, along with the dozens of short stories anthologized all over the place in the ’90s. I read, and re-read, everything with Koja’s name on it. Though often labeled as “horror,” these pieces weren’t like the other horror stuff I had my hands on –no ghosts, no vampires, no demon-possessed cars. All the poison and horror and secret stuff came from inside, not outside, her characters. That’s where I still want to be, as a writer—deep inside, lurking around with the same insatiable voyeuristic impulse of my childhood self, trying to catch someone with their pants down and their blood spilled.

Kathe’s voice spoke to me, for me, ahead of me, and her influence runs deep. When I’m editing a story, there’s always a point where I have to say to myself, no, that’s Kathe’s, and I have to delete whatever bit I’ve unconsciously cribbed. I’ve changed a lot, I hope, in the past twenty years, but the seeds of my style, my literary worldview, my sense of what is possible—so much of that comes from Kathe. The blood of those books is in my veins and I’m so grateful for it, and for that Tower Records, now vanished, which brought us together.

Kathe—whom I met at a reading two years ago—is now a dear friend. And, not surprisingly, she is every bit the badass those ’90s author photos suggested she was (seriously, check them out, they’re epic). She continues to rip genre expectations to shreds; her forays into YA and historical fiction and theater are every bit as transcendent as her early work. Kathe Koja, my Art Mom, is still blazing trails, and I’m still taking notes.

24 July 2016 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.