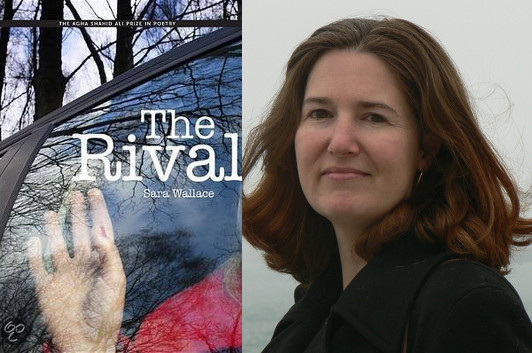

Sara Wallace: Smoke in Streams of Light

photo: Rose Ann Franklin

Sara Wallace writes poems with vivid details, immersing you in her scenes, whether it’s a walk through the narrator’s grandparents’ farm in “Take This Old Coat” or the unflinching depiction of an abusive relationship in “You.” But her poetry can’t be reduced to “naturalism” on the one hand or “raw emotion” on the other; it’s the two elements in tandem that make the poems in The Rival stand out. It’s a point she takes up in this guest post, with reference to some of her own favorite poets…

I wanted to start with noir.

A woman’s dress like a tight shadow,

her fingertips dipped in darkness.

Beauty reduced to Glamour and made Suspect.I am endlessly fascinated by Reality and Imagination and my favorite writers comment on and complicate this supposed binary. On one side, we have Reality—the commonplace, the solid, common sense, “salt of the earth” people and the hum-drum comfort of greasy spoons, where we “burst the bubble,” and “come back down to earth,” but where we also see “the cold light” and “hard truths,” where humankind’s greed and brutality are mundane givens. On the other side, we have Imagination—that imaginary get-away with a longed-for yet imminently unattainable Beauty, the “mystic visions and cosmic vibrations” (Allen Ginsberg, “America”) of faith, encounters with inspiring art, where there is charm, elegance, and wonder but where there is also affectation, ostentation, pride, “spells and incantation” (Keats, “To…”), and the constant danger of aesthetic failure (“I am going to dream up a tiger,” Borges writes in “Dreamtigers.” “Utter incompetence! A tiger appears, sure enough, but an enfeebled tiger…” )

Indeed, each side of the binary actually has multiple binaries within it, like the fractals studied in chaos theory. The most interesting contemporary poets play with this “hall of mirrors” effect. For example, Jack Gilbert’s poem, “Alyosha,” opens with a quasi-Gauguinian moment, with the narrator seemingly fetishizing locals: “the sound of women hidden / among the lemon trees.” The work as a whole, however, is hardly a simple celebration of primitivism (which, after all, exists in the imagination of the beholder). Gilbert’s disillusioned narrator knows that the reality of Beauty’s life is often terrible even as he covets her: “He is not innocent. / He knows the shepherdess will be given / to the awful man who lives at the farm /closest to him….”

What at first appears to be an admission of his own romanticism (“a sweetness that lives in the mind”) slowly becomes an argument for it (“he longs to live married to slowness”) and a realization that when Reality and Imagination, the symbolic and the literal, fuse our lives are more rich: he both “lives now with the lambs” (literal lambs, it is a poem about shepherds) and “watches them being eaten at Easter to celebrate Christ.”

Even the fiction of my favorite poets addresses the Venn Diagram of Reality and Imagination, in which what we think is hallucinatory and what we think is real is utterly and wonderfully conflated, like in the opening pages of Denis Johnson’s novel Jesus’ Son:

The traveling salesman fed me drugs that made the linings of my veins feel scraped out…. I knew every raindrop by its name. I sensed everything before it happened. I knew a certain Oldsmobile would stop for me even before it slowed, and I knew by the sweet voices of the family inside we’d have an accident in the storm.

These writers know Imagination doesn’t stand in opposition to Dreary Reality. If it did, it could never touch it.

Lizards crawling over book jackets.

Knife-slash shadows filmed in black and white.

Smoke in streams of light.

7 July 2015 | poets on poets |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.