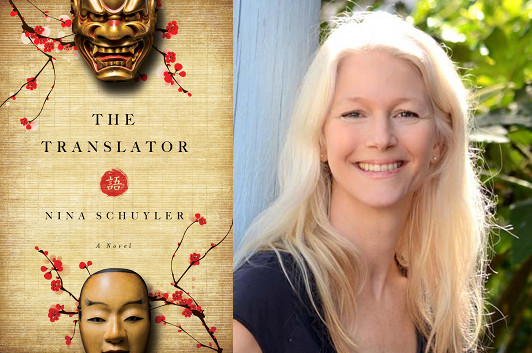

Nina Schuyler Has Translation on the Brain

photo: Cristina Taccone

As Nina Schuyler explains below, the protagonist of her new novel, The Translator, thinks she understands the Japanese novel she’s rendering into English, but she may be looking at it from a skewed perspective. What happens when the rest of her life is thrown into disarray by a brain trauma that takes away her ability to speak English—but leaves her fluent in Japanese? That would be telling, of course… but I can share Schuyler’s insights into what drew her, as a novelist, to this captivating premise.

In 2005, The New Yorker published an article by David Remnick, “The Translation Wars,” about a married couple that was busy re-translating all the great Russian novels into English: Richard Pevear, an English speaker, and his wife, Larissa Volokhonsky, a Russian émigrée. Finally, what Nabokov called a “complete disaster” and “the dry shit” of Constance Garnett, who had first translated Russian literature into English, could be set aside.

What caught my eye wasn’t the word “Translation” in the title of the article, but the words “Tolstoy” and “Dostoyevsky” in the subtitle. As a girl, I fell in love with Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy, Chekhov, and Pasternak. I remember one summer when I was twelve, I carried Doctor Zhivago every day to the pool. Back then, I didn’t even consider that the stories were first written in Russian—what Thomas Mann called “the muddy, barbaric, boneless tongue from the East.” What I thought about was snow, sleigh rides, passion, betrayal, revolution, peasants, czars, love.

Constance Garnett was, in fact, English. In 1891, when she had a difficult pregnancy, she taught herself Russian. Soon she began translating. According to Remnick, when she came across a word or phrase she didn’t know, she merrily skipped it and moved on. She was not skilled enough to carry forth certain verbal motifs and complicated sentences.

I went to my bookshelf. My Russian literature—all Garnett’s translations! Watered down, corrupted translation, soaked in a heavy dose of English custom and sensibility. As all writers learn, conflict makes for story. The New Yorker article presented itself to me as a seed for a story: What if a translator thinks she did a superior job, as Garnett most likely did, but, in fact, mangled the job?

I credit my experience as a journalist for giving me the hubris to take on something that I know little about. I’m not a translator, but I know how to conduct an interview. I ended up speaking to eight translators, who translate Japanese literature and business documents into English. When one translator said to me, “I only take on a project of literature if I can relate to and understand the main character,” I sat up. My main character, Hanne Schubert, a 53-year-old translator, was beginning to come alive. What if Hanne thought she related to and understood the main character of a Japanese novel that she was translating—but, in fact, she did not?

Part of writing fiction is swimming in the unknown. Unlike nonfiction, there are no parameters, at least early on, in terms of the plot, story, character. I let myself research and explore language, translation, and Japan. I conducted an interview with a neuroscientist who explained that a language learned later in life is located in a different area of the Broca region, which is found on the frontal lobe. So a trauma to the brain can knock out one language, while leaving another intact. In fact, there are one or two cases like this every year.

So what if Hanne falls down a flight of stairs and is left speaking a language she learned later in life—Japanese? She lives in San Francisco, but none of her friends speaks Japanese. As the days go by, she becomes increasingly isolated. She’s built a life around her work, but after the fall, she’s unable to focus, and her isolation becomes unbearable. So of course she’d head to Japan, where she’d been invited to give a lecture on translation.

Luckily, I stumbled across the fascinating research of Lera Boroditsky, a cognitive psychologist at Stanford University. She (and other researchers) found that the language one speaks affects perceptions of the world. In fact, this notion existed back in the 1930s, but was abandoned in the 1970s in favor of theories claiming that language and thought are universal. Now enough empirical evidence has been gathered to revive the old theory. Speakers of Japanese or Spanish, for instance, are less likely to mention the agent when describing an accidental event. If I accidentally knock over a book, for instance, a Japanese speaker is likely to say, “the book fell” rather than “Nina knocked the book to the floor.”

Boroditsky has found this has consequences for memory. She showed videos to Japanese, English and Spanish speakers of two guys popping balloons, breaking eggs, spilling drinks either intentionally or accidentally. Later, she gave them a memory test. For each event, the subject had to say which guy did it. Spanish and Japanese were less likely to identify the person who caused the accident compared to English speakers.

So what happens when Hanne sinks further into Japanese, not only speaking it, but dreaming in Japanese? How might she begin to think differently? How will this change her life?

I was transfixed by the complexities that exhausted easy explanations. I was caught up and imagined willingly being caught up for years. The more I explored, the larger the pile of questions. I had, to my delight, the beginning of a novel.

11 November 2013 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.